Notes on Mr. Eliot's Algonquian Bible, a Birthday Gift for Mr. Baker's Library

December 1978 R. H. R.Notes on Mr. Eliot's Algonquian Bible, a Birthday Gift for Mr. Baker's Library R. H. R. December 1978

The book begins this way:

"I. Weike kutchinik a ayum God Kefuk kah Ohke.

"2. Nah Ohke mo matta knhkenauunneunkquttinnco, kah pohkenum woskeche moonoi, kah Nashhauamt popomshau woskeche nippekontu."

The language is Algonquin, and those are the first two verses of the Book of Genesis. They are taken from a remarkable rare book purchased for and donated to the College last spring just in time for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the opening of Baker Library.

Given by an anonymous donor in honor of the late Arthur R. Virgin '00, the book most frequently goes by its short title: the "Eliot Indian Bible." Its full title is somewhat more ponderous: Mamusse WunneetupanatamweUp-Biblum God, Naneeswe Nukkone Testament, Kah Wonk Wuskee Testament. Among the two or three most significant American Colonial imprints, the book was printed by the Cambridge Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1663 and has been called by one bibliographer "the most extraordinary volume of the Cambridge press, and indeed of the whole colonial period." It is also one of the rarest. Of an astonishingly large (for 1663) edition of 1,500 copies, something less than 40 are known to survive today.

The Reverend John Eliot (1604-1690), born in England and educated at Cambridge, emigrated to America in 1631. Although he held a pastorate in Roxbury, Massachusetts, he conceived his major mission to be conversion of the Indians to Christianity. Faced with his own New World version of the confusion of Babel, he set about learning the Indian language and after some years of study became so proficient that he preached to the Indians in their own tongue. Not content with that accomplishment, he then spent another ten years translating the entire Bible into the Algonquian language.

Eliot's Bible was not only one of the finest achievements of Colonial scholarship; it was also the tour de force of Colonial printing. Having persuaded perhaps the most skillful printer in the Colonies, Samuel Green of Cambridge, to take on the monumental task of printing his 1,200-page Bible, Eliot then sought financing for his project from the home country, specifically the English Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Indians, which was based in London. The society responded enthusiastically; it not only sent a new press and new type to the Massachusetts Bay Colony but also a young English printer, on a three-year contract, to help Green with the printing.

Using two wooden hand presses and proceeding at the rate of about one sheet per week, the two printers, along with an Indian convert supplied by Eliot and called James Printer, took three years to complete the work. Some 145 years later, in 1810, the famous Worcester printer Isaiah Thomas could still marvel at the achievement. "At that early period of the settlement of the country" the book was "a business difficult to accomplish, and of great magnitude," he wrote. "It was a work of so much consequence as to arrest the attention of the nobility and gentry of England, as well as that of King Charles, to whom it was dedicated." With this single publication the Cambridge Press became "for a time, as celebrated as the presses of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, in England."

Baker Library is not lacking in rare books. Several thousand of them, are housed in Special Collections under the care of Walter W. Wright, curator of rare books. Some - an Audubon elephant folio, for instance, or the four Shakespeare folios - are perhaps even rarer than the "Indian Bible." But few seem more appropriate to Dartmouth College, to its history and its very reason for being, than the Reverend Mr. Eliot's old "Indian Bible."

What could be more fitting? Along with several other commodities, famed in song and legend, which Eleazar Wheelock is purported to have brought with him up the Connecticut River was of course a Bible. Perhaps it was the "Indian Bible." Most likely not. Eleazar's rare book budget was no doubt somewhat limited, and even in 1770, after all, the "Indian Bible" was an old, and rare, book.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCrime and Punishment

December 1978 By Tim Taylor -

Feature

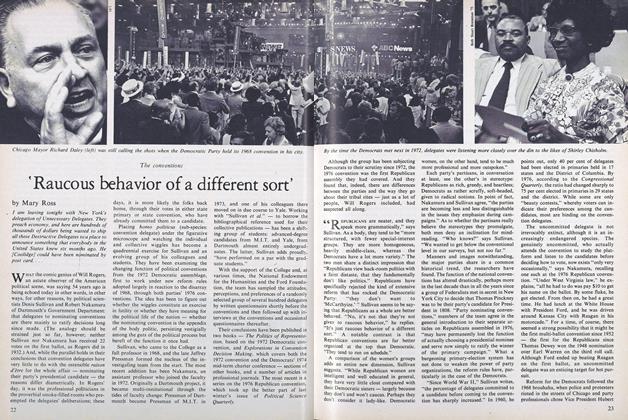

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureParadise Lost or Paradise Regained?

December 1978 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD NEWS

December 1978 -

Article

Article'Most Improved Professor'

December 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N.

R. H. R.

Books

-

Books

BooksA History of English Literature

March 1918 -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED STATES--EXPERIMENT IN DEMOCRACY,

February 1948 By Allen R. Foley '20. -

Books

BooksA SHORT FRENCH GRAMMAR FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS

May 1940 By Charles R. Barley -

Books

BooksCONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GEOLOGY OF URANIUM AND THORIUM:

October 1956 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksINVESTMENT, PRINCIPLES AND ANALYSIS

June 1938 By John W. Harriman. -

Books

BooksGame Plan

March 1980 By Thomas R. English ’70