ALMOST two hundred years ago, the ring of John Ledyard's axe cut the stillness of the pine forests that shrouded Hanover. One of Dartmouth's first students was leaving probably the College's first dropout and he saw to it that President Eleazar Wheelock was not around to say goodbye!

With the help of some of his fellow students, Ledyard had felled a giant pine, cut it into a 50-foot length, and hollowed out its three-foot girth into a rough dugout canoe, capable of taking him back to his grandparents' home on the banks of the Connecticut River at Hartford.

President Wheelock hadn't liked it when Ledyard took off in the middle of his first winter in Hanover to spend several weeks with a tribe of North Country Indians; and Ledyard hadn't liked it when Wheelock assigned to him the degrading task of blowing the conch-shell each day to summon his fellows to classes. President and student just never hit it off!

Ledyard was not opposed to a classical education, but he didn't seem to appreciate Wheelock's missionary ways. Ledyard had studied in a Hartford law office before coming to Hanover, and he apprenticed to a clergyman in Connecticut after he left the college in the hills. When he leaped into his dugout canoe, and pulled his bearskin over him, he clutched in his hands two books one a Greek Testament and the other Ovid.

Ambassador to France Thomas Jefferson chuckled over this story fourteen years later in Paris; the dropout had left school but he had taken his books with him!

The story of John Ledyard is not well enough known by Dartmouth men today. He was one of the great adventurers of Revolutionary America, dedicated to the geographic oneness of the world and to the spiritual oneness of man.

Even as a young man, he was a fiery and independent character. When he reached Hartford, and found out that President Wheelock had written critical letters to his grandparents, he sat down and wrote to the Reverend Eleazar in Hanover:

"I take what you have said, in regard to my pride, very ill-natured, very unkind of you. So far as I know myself, I came to your college under influences of the good kind, whether you, sir, believe it or not. The acquaintance I have gained there is dearer than I can possibly express. Farewell, dear Dartmouth. ... I am, honored and reverend sir, though sorely beset, your obliged and dutiful young servant."

John Ledyard went on from Hartford to London. He sailed with Captain Cook on his last, historic voyage of exploration to the Pacific, wrote an authoritative journal of that mission, and forecast the commercial possibilities of the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest.

With the help of Ambassador Jefferson and General Lafayette, he planned a trip around the world, the first such effort from west to east, and was halted only when the Empress of Russia finally had him arrested as he had nearly completed his crossing of Siberia.

He noted the nearness of the continent of Asia to the continent of North America at the Bering Strait, and speculated on the common origin of the peoples of Siberia and Polynesia and the American Indians - the first such speculation. He was probably the first human being to be acquainted with all three peoples.

He believed in the future of the continent of Africa, and died in Cairo while en route into the interior in the service of the African Association, a private exploration group in London of which the King of England was chief patron.

For Ledyard, the world was oceans and rivers, continents and forests, and the world was people. True, there were people of different colors and different tongues, but wherever he went he was struck by their similarities, not their differences.

Everywhere he found similarities in the way people built their houses, prepared their food, cared for their young, made love, fished and hunted, or traveled by canoe and horseback; the differences were usually man-made, and worse, government-made.

Ledyard would have been a good witness against pending Administration legislation to impose new restrictions upon the right of American citizens to travel in foreign lands.

Ledyard tolerated no national boundaries, and there is considerable evidence that when he discovered one, he defied it. Man was made to be free, he reasoned, and surely, a fundamental right of a country fighting for political freedom should be freedom of travel.

It is hoped that this Ledyard spirit of travel freedom may pervade a new generation of Dartmouth canoeists and Dartmouth men. There are still imposing national boundaries to be broken, and new frontiers to be pioneered.

Two hundred years after Ledyard, we know less about Siberia than he did! We know little more about central Africa! We are completely out of touch with mainland China, with which Ledyard hoped to maintain a lively and profitable fur trade.

Dartmouth men, aware of the Ledyard story and fired by the Ledyard spirit, have better reason than most to bring this ignorance and divisiveness to an end. Some of the sons of the College are doing this already.

The Dartmouth canoe trip down the Danube in 1964 may well have done more for" East-West relations than anything achieved in Washington in recent years. Dan Dimancescu, Chris Knight, Bill Fitzhugh, Dick Durrance, and their associates paddled 1,685 miles through eight countries in 73 days. Their music, their knowledge of their hosts' countries and languages, their adventuresomeness, their courage and skill made friends everywhere - in the Ledyard spirit.

What this country needs is not more travel restrictions, not the conversion of a passport from an historic badge of honor asking privileges abroad into a restricted license for supine citizens to leave their own country. We need more Danube trips, and more sons of Ledyard ready to make them!

There are great rivers in China. In Africa. In South America. There are great rivers in Russia. John Ledyard was halted at Yakutsk on the Lena River in 1788. Who is there to finish that Ledyard trek across Russia and Siberia to the sea?

John Ledyard spent a short lifetime of 37 years defying the efforts of every government that kept its serfs in subjugation, that divided its people, that preached internal or external hatred.

Ledyard was raised on the Puritan virtues of charity and kindness, but he declined to follow the ministry or the law, preferring apparently to make his life a sermon on the brotherhood of man. The sermon needs remembering today — it needs preaching anew.

Dartmouth College should preach it by setting aside the level land on the New Hampshire shore to the north of the Ledyard Bridge as "John Ledyard Park," to preserve the natural beauty of a spot dear to the hearts of all Dartmouth men and to keep alive the story of the pine that was felled in 1772 leaving a significant space in the colonial sky.

We should preach it too by replacing the Ledyard Monument, pockmarked with a vandal's rifle Are for more than fifty years. Ledyard deserves a monument that will stand as a great work of art, as noteworthy and timeless as the life it commemorates.

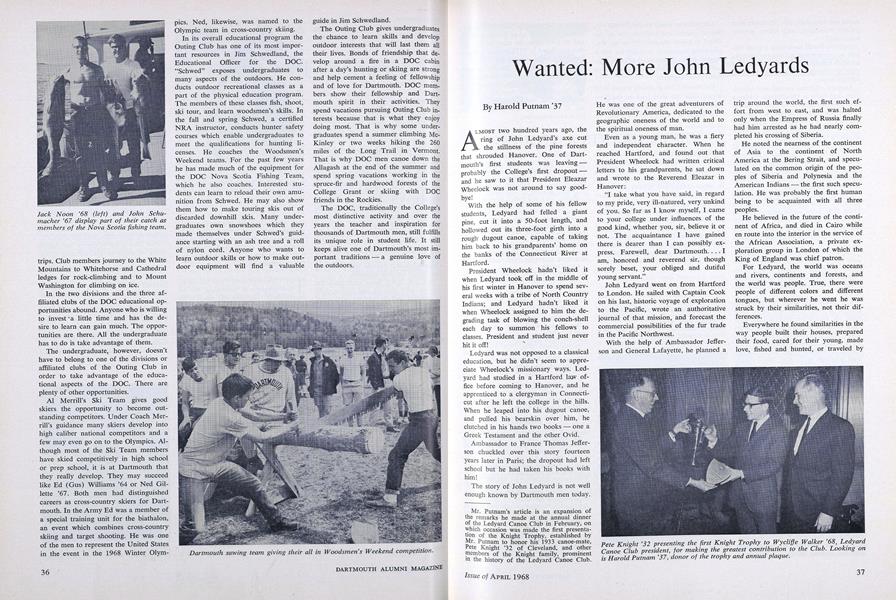

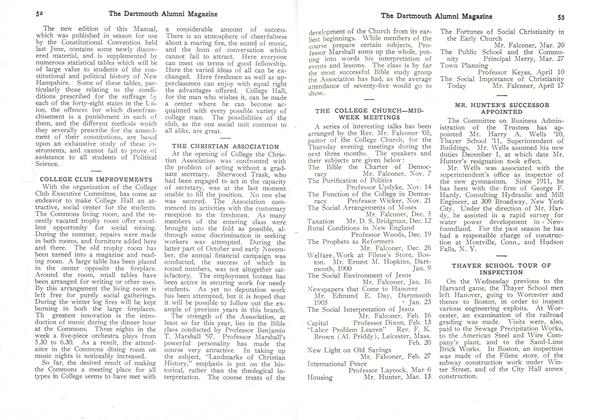

Pete Knight '32 presenting the first Knight Trophy to Wycliffe Walker '68, LedyardCanoe Club president, for making the greatest contribution to the Club. Looking onis Harold Putnam '37, donor of the trophy and annual plaque.

Mr. Putnam's article is an expansion of the remarks he made at the annual dinner of the Ledyard Canoe Club in February, on which occasion was made the first presentation of the Knight Trophy, established by Mr. Putnam to honor his 1933 canoe-mate, Pete Knight '32 of Cleveland, and other members of the Knight family, prominent m the history of the Ledyard Canoe Club.