ANATOMY OF DIPLOMACY: THE ORIGIN AND EXECUTION OF AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY.

JULY 1968 RICHARD L. WALKERANATOMY OF DIPLOMACY: THE ORIGIN AND EXECUTION OF AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY. RICHARD L. WALKER JULY 1968

By Ellis O.Briggs '21. New York: David McKay Co.,1968. 248 pp. $5.95.

These are days when political scientists, propelled by the computer revolution, are busily quantifying every conceivable political process and then attempting to communicate their findings in a jargon almost as unintelligible as it is abstruse. It is refreshing, therefore, to have the background and current status of United States foreign policy surveyed by a professional diplomat who does not forget the human factor and who writes with lucidity, wit, and the benefit of practical experience.

Ellis Briggs, who has been a Foreign Service Officer for almost four decades and a Career Ambassador to eight capitals, has turned his considerable literary talents to a brief survey of how American foreign policy is formulated and enacted and then to a once-over-lightly of the diplomatic problems posed for Uncle Sam in relations with the UN, the Communist powers, the new nations, Latin America, and finally with the revolutionary world of the atom bomb and the population bomb. In the course of this survey, which could well serve as an introductory college text on the conduct of U.S. foreign policy (and it would prove that textbooks do not necessarily have to be dull to be informative) Briggs is once again taking pot-shots at his favorite targets: burgeoning bureaucracy and amateurs attempting to play at the game of diplomacy (where they are just about as equipped as the Hanover High School is to take on the Green Bay Packers).

To those who chortled their way through Farewell to Foggy Bottom this latest volume of felicitous phrase-turning will be equally enjoyable, but it is more informative. The ambassador has explained how the various institutions in the United States Government operate and relate to one another in the conduct of foreign policy. One chapter, "A Day with the American Ambassador, or What Makes an Embassy Tick," should be required reading for those frequent American tourists who seek audiences with our ambassadors abroad and then with almost equal frequency attempt to coach them on how they should conduct our nation's business.

But let us face it: there are going to be many readers who will not like Anatomyof Diplomacy. This reviewer can just picture Ambassador Briggs sitting back and enjoying every one of the anguished howls which some of his judgments and recommendations will evoke. He remarks (p. 132) "the great uninhibited American penchant for sounding off," and in page after page he then demonstrates that he is a qualified American. The major target which he attacks from all directions is the increasing bureaucracy of the American government and its invasion of the premises of the professional diplomat and impeding the work of diplomacy. With great spirit and bountifully amusing examples Briggs is only too willing to engage in gladiatorial contest with the "teeming protagonists of the managerial revolution." Believing as strongly as he does that "a crusading spirit is not a foreign policy," he is obviously less than enthusiastic, for instance, about the Peace Corps or for that matter about many other organizations which the American government has spawned abroad.

The general thesis of the volume is that representation of the United States abroad is a subtle and complicated business and that therefore it should be left to the professionals. Ambassador Briggs is a staunch defender of our Foreign Service (the book is dedicated to its members). He notes that the Department of State and the Foreign Service are often unjustly the targets of criticism and denunciation in an America that feels its wish should become international fact. With "no Washington lobby, no constituency to wound, and no megaphone to shout back through," the occupants of Foggy Bottom become an "ideal target whenever a miscalculation has been made, or a toe has been stubbed, or a brickbat is there to be thrown."

Though the ambassador recognizes the prodigious changes in terms of tempo, scope, and range of the "new diplomacy," it is clear that he would prefer to return to the more leisurely pace of the inter-war period. Yet he does have a very important point to make in calling our attention to the shift away from the traditional objective of diplomacy, influencing policy, to the goal of influencing foreign institutions. It is this shift which Briggs feels reflects the American tendency to embark on a crusade to remake the world and which has been primarily responsible for our overcommitment and some of our policy failures abroad.

In an age when all sectors of American society are increasingly concerned about foreign policy issues, when the American travels abroad as never before, when the Communist states continue to harass the free world and plot its demise, it is important that our citizens understand how American foreign policy operates. It is hoped that they will turn to Ellis Briggs' stimulating volume; it can help them put in clearer perspective the most important determinant of their future: America's position in the world today.

Since this reviewer is expressing his admiration for Ambassador Briggs' latest volume in the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE, he would be remiss if he did not note that Ellis Briggs' pride in his alma mater was only too well known in every embassy where he served. One of the members of his staff in his last post, Athens, has confided that there was constant speculation among the staff whether the ambassador's underwear was actually Dartmouth green in color. To which one can only add the wish that Dartmouth continues to turn out graduates equally facile with words and equally capable of explaining American foreign policy.

Mr. Walker is the Director of the Instituteof International Studies, University of SouthCarolina.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

July 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

Feature"People as Well as Things"

July 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1968 By JAMES WITTEN NEWTON '68 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

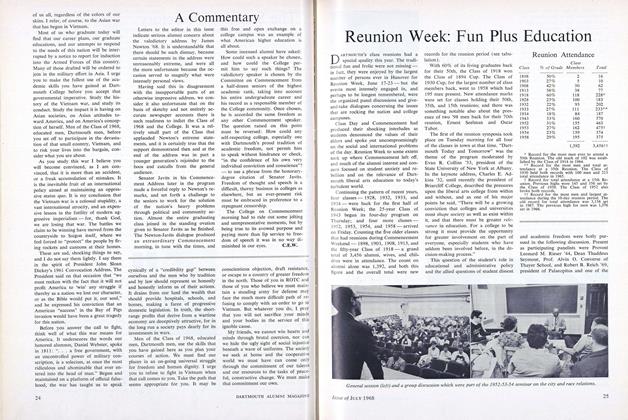

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

January 1921 -

Books

BooksEXPERT SKIING.

February 1961 -

Books

BooksAPOLLINAIRE: POET AMONG THE PAINTERS

MARCH 1964 By GEORGE E. DILLER -

Books

BooksSCENERY OF THE WHITE MOUNTAINS.

MARCH 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksMARKETING MANAGEMENT.

January 1962 By Louis P. BUCKLIN '50 -

Books

BooksGOVERNMENT REGULATION OF BUSINESS: A CASEBOOK.

FEBRUARY 1966 By WILLIAM L. BALDWIN