Dartmouth's exquisite manuscripts

The curator of Dartmouth's manuscripts describes the College's collection of illuminated manuscripts as"very small but exquisite." Philip Cronenwett, a medieval historian, came to Dartmouth in 1979 as the College's first formal curator of manuscripts, and he is continually surprised by what he unearths in the bowels of Baker Library's Treasure Room. The entire

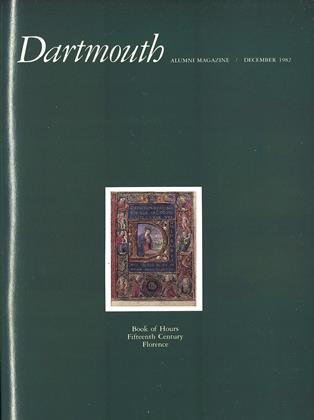

manuscript collection, some five million items, represents a continuum from the thirteenth century B.C. (cuneiform tablets) to the present day ("I throw in computer tapes," says Cronenwett). In the middle of the time span fall Dartmouth's several hundred medieval manuscripts, one of the finest of which graces our cover this month.

For about a thousand years, between the fall of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Italian Renaissance, manuscript illumination, begun in monastic communities and continued in secular workshops , was the principal form of western painting. Though the earliest surviving illustrated books are mostly works of Homer and Virgil, it was the rise of Christianity in the fourth century A.D. that provided the real impetus for the development of the illuminator's art. Christianity is a very book-oriented religion, with its popularly-disseminated Bible and its reverence for the Word. "In the beginning was the Word," reads the Gospel of St. John, "and the Word was with God, and the Word was God," and in an age in which reading and writing themselves were regarded as magical, the adornment of the sacred Word became a high form of religious expression. The art rose first in Constantinople and flourished throughout the Christian world. Italy, Ireland, and England had their pre-eminent hours on the stage, as did Germany, France, and Spain, and Flanders and the Low Countries also produced masters of illumination.

Illumination held sway as the main vehicle for painting until the end of the fifteenth century, when panel painting, and then mural and easel painting came to the fore. The arrival of printing sounded the death knell for the delicate art though it enjoyed a brief revival late in the nineteenth century, and even today a tiny handful of illuminators are still at work, most of them in religious communities, patiently weaving together text, ornament, and picture in the old way, and emphasizing, flatness, brightness, and decorative harmony over verisimilitude.

Medieval manuscripts were made of vellum, usually calfskin. The text was written in black on the unbound leaves by the calligrapher, who left blank pages and initials

that were to be illuminated and then turned them over to the miniaturist, who outlined the drawings first in pencil, then in ink. Next any gold or silver to be used was applied, and finally the brilliant colors in water-soluble pigment. Shadows and highlights came last, after which the folios, or pages, were sent to the binder.

Housed as they were between sturdy leather covers and in libraries, many illuminated manuscripts have survived in pristine condition and can serve us as tiny windows on the medieval world visual histories of medieval society and values. Paradoxically, because they have been so long in libraries, they have not been generally available to the public, a situation Cronenwett would like to remedy. Dartmouth's holdings are a teaching collection, he points out, and he does not believe in hedging them around with restrictions. "They are available to anyone with clean hands and functional literacy," he says and, indeed, for the mere asking, he will lay before you several million dollars' worth of some of the College's loveliest treasures.

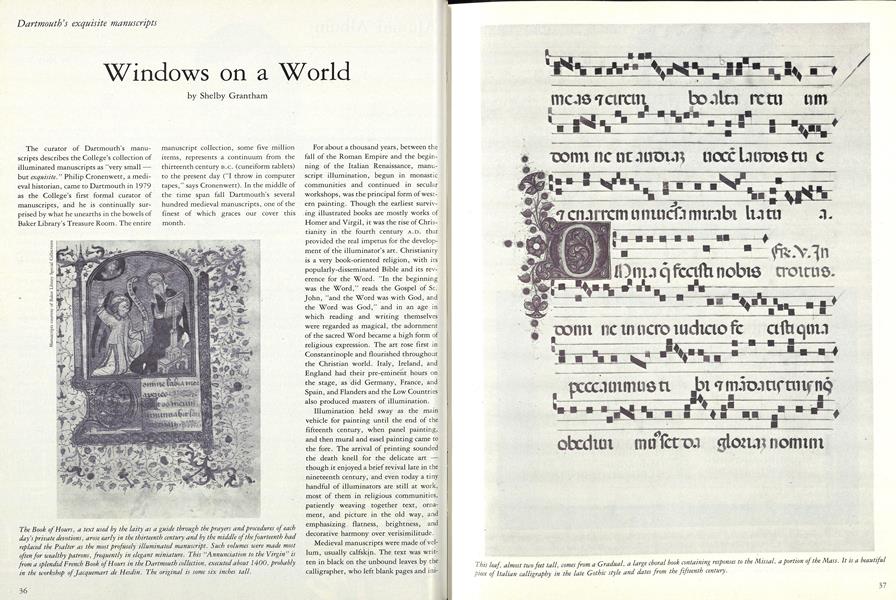

The Book of Hours, a text used by the laity as a guide through the prayers and procedures of eachday's private devotions, arose early in the thirteenth century and by the middle of the fourteenth hadreplaced the Psalter as the most profusely illuminated manuscript. Such volumes were made mostoften for wealthy patrons, frequently in elegant miniature. This "Annunciation to the Virgin" isfrom a splendid French Book of Hours in the Dartmouth collection, executed about 1400, probablyin the workshop of Jacquemart de Hesdin. The original is some six inches tall.

This leaf, almost two feet tall, comes from a Gradual, a large choral book containing responses to the Missal, a portion of the Mass. It is a beautifulpiece of Italian calligraphy in the late Gothic style and dates from the fifteenth century.

This illustration is an "Annunciation to the Shepherds" from aBook of Hours some seven and ahalf inches tall, probably thework of a French miniaturistdone around 1495, when manuscript illumination was enteringa decline. In it, the borders ofnaturalistic plants and birdscommon to the Gothic style giveway on occasion, as here, to theheavy architectural frames of thelater Renaissance style.

This magnificent book of prayers, reproduced here full-size, is believed to be unique in the annals of decorated manuscript. It was made about 1600 byDiego de Barrada, a Dominican monk, for King Philip III of Spam, and its exquisite calligraphy is neither penned nor brushed. It is cut. Each of the88 pages is a stencil, laboriously cut with some unimaginably precise tool held in an equally unimaginably precise hand. A piece of richly-colored silk - green, red, black, blue, or yellow —is sandwiched between each pair of consecutive pages, which are sealed at their edges. The whole is gathered intoan elaborately gilt leather binding, and its edges are gilt and gauffered (cut across with a design in shallow relief).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhere They Hang Their Hats

December 1982 By Steve Farnsworth and Jean Korelitz -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

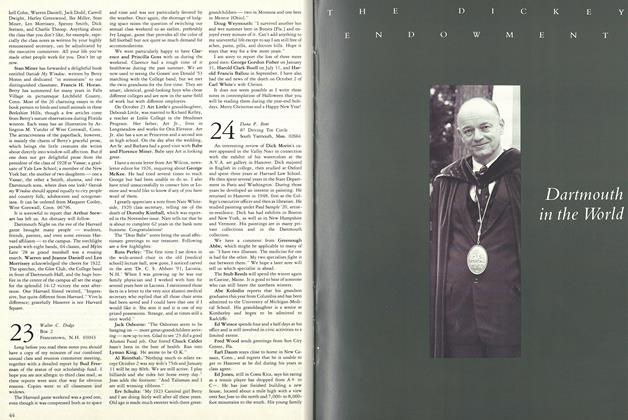

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

December 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47

Shelby Grantham

-

Article

ArticleMagic in the Museum

Jan/Feb 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

NOVEMBER 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRetirement Nears for Seven Dartmouth Professors

JUNE 1959 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth on Capitol Hill

JANUARY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT

JUNE • 1986 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SKIWAY

January 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

SEPTEMBER 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51