ByAdrian A. Paradis '34. New York: JulianMessner (Simon & Shuster), 1969. 94 pp.$3.95.

If I may be permitted an entirely unjustified paraphrasing of Prof. Paul Samuelson's remarks on Keyne's General Theory, "I must confess that my own first reaction to [Trade, The World's Lifeblood] was not at all like that of Keats on first looking into Chapman's Homer. No silent watcher, I, upon a peak in Darien. My rebellion against its pretensions would have been complete, except for an uneasy realization that I did not at all understand what it was about." As a consequence, I turned to a consultant whom I know and respect for guidance, my 13-year-old daughter Karen. The result of this happy collaboration is the following review.

Mr. Paradis has written a spritely account of random elements connected, with the history of world trade. This book, apparently aimed at an audience of 10- to 12-year-olds, is not a consistent development of any particular theme. Its unifying thread is the fact that these are stories or observations about trade arranged chronologically. And as such it is good - very good in fact. We believe that it is much more interesting than much of the social studies material the average 6th grader is forced to plod through in his study of commerce between nations. As a highly readable supplement to a basic social studies text it is recommended to teachers and students alike. It should spark an interest for further study of trade among many of its readers, covering as it does the primordial period of trade through the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans, on into the Dark Ages, the Renaissance, the discovery of the New World, and ending finally with observations on the future of the international exchange of goods and services.

We do have one technical suggestion. The glossary, while helpful, would be of greater value if it were incorporated piecemeal into the text. Certainly a word such as "monopoly" is more easily understood by the student if it is explained immediately rather than if he has to refer to the back of the book - which he won't! Also, the glossary is a bit uneven. The definition of "competition" - "rivalry between persons or firms for cusomers" is far superior to that found in most college micro-economic theory texts. On the other hand, the definition of "subsidy" as "Money given by a government to a private company to benefit the public" ignores completely subsidies such as those to the oil industry which benefit the industry at the expense of the public.

8th grader, Lyme School

Associate Professor of Economics

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

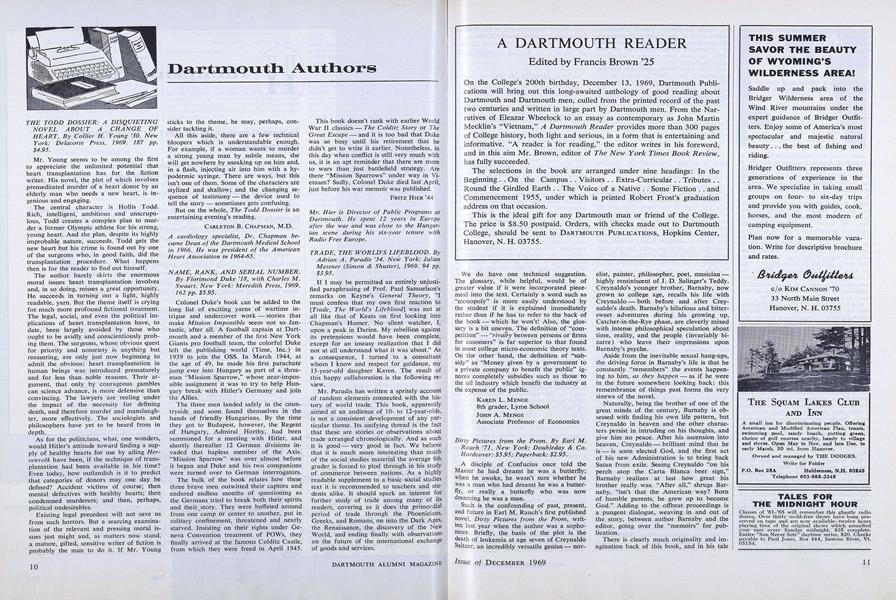

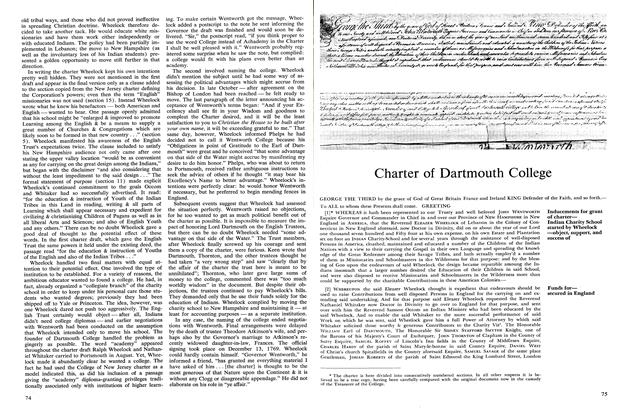

FeatureEleazar Wheelock and the Dartmouth College Charter

December 1969 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55, -

Feature

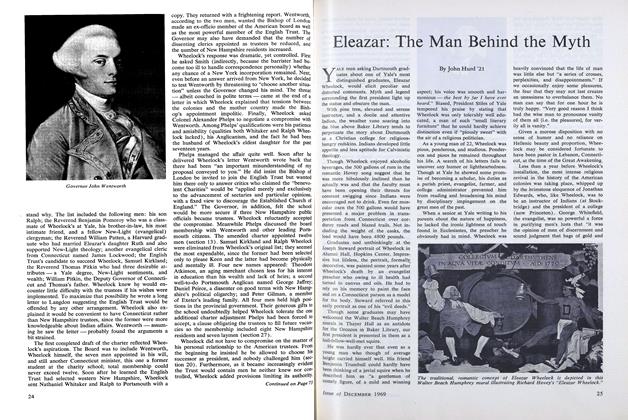

FeatureEleazar: The Man Behind the Myth

December 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

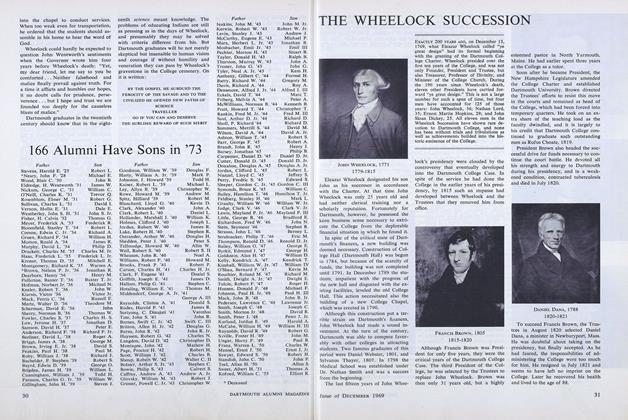

FeatureTHE WHEELOCK SUCCESSION

December 1969 -

Feature

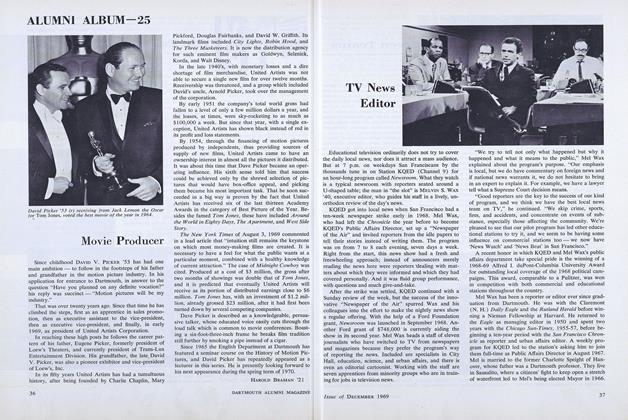

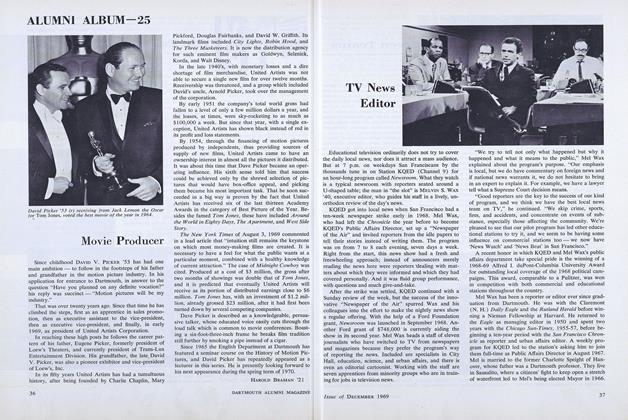

FeatureTV News Editor

December 1969 -

Feature

FeatureMovie Producer

December 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

ArticleCharter of Dartmouth College

December 1969

JOHN A. MENGE

Article

-

Article

ArticleMath Exams Wanted

December 1938 -

Article

ArticleThe Fraternities: On Probation

March 1979 -

Article

ArticleCount Rumford and DOC Fireplaces

MAY 1963 By ALLEN P. RICHMOND JR. '14 -

Article

ArticleResults of Risks

AUGUST 1929 By Ambrose W. Vernon -

Article

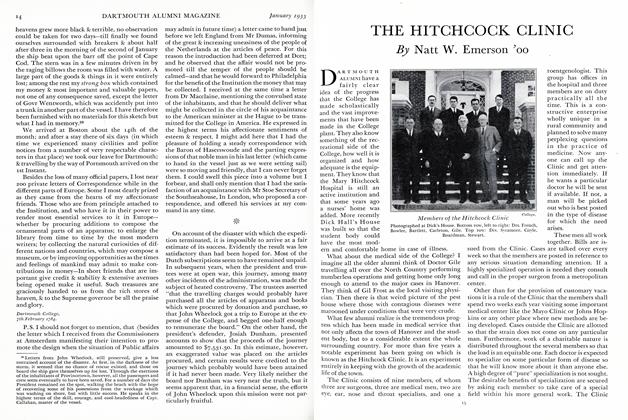

ArticleTHE HITCHCOCK CLINIC

January 1933 By Natt W. Emerson '00 -

Article

ArticleThe Harvard-Dartmouth Expeditions to Alaska

April1935 By Richard P. Goldthwait '33