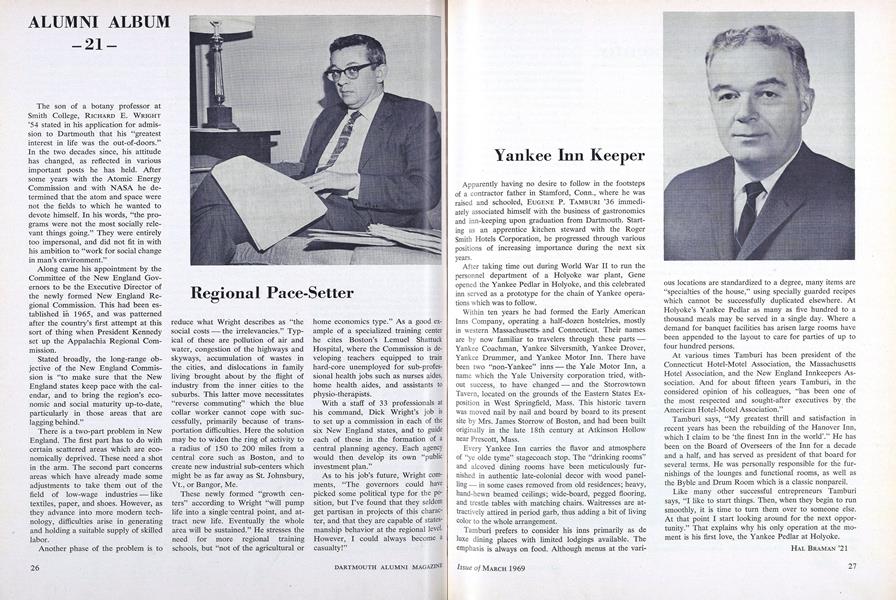

The son of a botany professor at Smith College, RICHARD E. WRIGHT '54 stated in his application for admission to Dartmouth that his "greatest interest in life was the out-of-doors." In the two decades since, his attitude has changed, as reflected in various important posts he has held. After some years with the Atomic Energy Commission and with NASA he determined that the atom and space were not the fields to which he wanted to devote himself. In his words, "the programs were not the most socially relevant things going." They were entirely too impersonal, and did not fit in with his ambition to "work for social change in man's environment."

Along came his appointment by the Committee of the New England Governors to be the Executive Director of the newly formed New England Regional Commission. This had been established in 1965, and was patterned after the country's first attempt at this sort of thing when President Kennedy set up the Appalachia Regional Commission.

Stated broadly, the long-range objective of the New England Commission is "to make sure that the New England states keep pace with the calendar, and to bring the region's economic and social maturity up-to-date, particularly in those areas that are lagging behind."

There is a two-part problem in New England. The first part has to do with certain scattered areas which are economically deprived. These need a shot in the arm. The second part concerns areas which have already made some adjustments to take them out of the field of low-wage industries like textiles, paper, and shoes. However, as they advance into more modern technology, difficulties arise in generating and holding a suitable supply of skilled labor.

Another phase of the problem is to reduce what Wright describes as "the social costs the irrelevancies." Typical of these are pollution of air and water, congestion of the highways and skyways, accumulation of wastes in the cities, and dislocations in family living brought about by the flight of industry from the inner cities to the suburbs. This latter move necessitates "reverse commuting" which the blue collar worker cannot cope with successfully, primarily because of transportation difficulties. Here the solution may be to widen the ring of activity to a radius of 150 to 200 miles from a central core such as Boston, and to create new industrial sub-centers which might be as far away as St. Johnsbury, Vt., or Bangor, Me.

These newly formed "growth centers" according to Wright "will pump life into a single central point, and attract new life. Eventually the whole area will be sustained." He stresses the need for more regional training schools, but "not of the agricultural or home economics type." As a good example of a specialized training center he cites Boston's Lemuel Shattuck Hospital, where the Commission is developing teachers equipped to train hard-core unemployed for sub-professional health jobs such as nurses aides, home health aides, and assistants to physio-therapists.

With a staff of 33 professionals at his command, Dick Wright's job is to set up a commission in each of the six New England states, and to guide each of these in the formation of a central planning agency. Each agency would then develop its own "public investment plan."

As to his job's future, Wright comments, "The governors could have picked some political type for the position, but I've found that they seldom get partisan in projects of this character, and that they are capable of statesmanship behavior at the regional level. However, I could always become a casualty!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJames Marsh, Dartmouth, and American Transcendentalism

March 1969 By Douglas M. Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureFaculty Votes Reduced Status for ROTC

March 1969 -

Feature

FeatureReaching Out from Hanover

March 1969 By Ron Talley '69 -

Feature

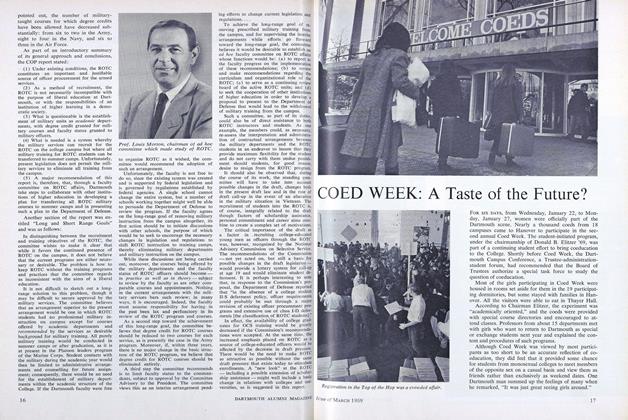

FeatureCOED WEEK: A Taste of the Future?

March 1969 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

March 1969 By WALTER S. YUSEN, WILLIAM C. VAN LAW JR.