The Inaugural Address of President John G. Kemeny, Delivered at his Installation as 13th President of Dartmouth College

IN AN AGE of student protest, one listens and one hears at least two major themes. One is a cry for a diversity in the educational process, and one is the demand for each person to be treated as an individual and to participate in a first-rate undergraduate education. One of these great cries is answered by large universities which are able to provide the maximum of diversity in the educational process, while the other is answered by the small liberal arts college. And one cannot help feeling there ought to be institutions that combine the best of both worlds.

Dartmouth College provides a broad liberal arts education for undergraduates. It provides professional training in mediring, cine, enginee and business administration. We are in the process of instituting a range of Ph.D. programs of some considerable breadth and we are fortunate to have great facilities, including a magnificent center for the creative arts, a superb library, and a unique computation center. We are, in the truest sense of the word, a university with all the diversity that the name "university" implies. And yet we are small.

There are very few true small universities in the entire nation. Yet I have hope that these small universities may represent a significant new third force in higher education between the great universities and the small liberal arts colleges.

I take considerable pride in the fact that amongst universities with the diversity I have described we are the smallest in the nation and smallness in this age is a major virtue. We have many other advantages: We are small enough that we still can function as a single community in which scholars with highly diverse backgrounds can cooperate and can do joint research. We are still predominantly an undergraduate institution; indeed, to me the historic decision to keep the name "Dartmouth College" rather than a university name is symbolic of ah eternal pledge that at least at one major university undergraduates will forever remain first-class citizens. When one adds to that our physical location in an area of natural beauty, in a part of the world where one can still breathe clean air and which is somewhat removed from the daily pressures of urban life, we are indeed a unique institution. And this uniqueness presents us with an opportunity - and I would say, therefore, an obligation - to set an example for higher education.

Let us consider what the priorities of such an institution should be. First of all any institution is a collection of people, and the quality of the institution cannot be better than the quality of the people who serve it. Clearly this says that we must have a first-rate faculty, but there are nearly 2,000 People serving this institution, and therefore we cannot limit our attention just to the faculty. I can say from my personal experience that the devoted secretary or the janitor who takes pride in the building he serves can contribute as much to quality of life on campus as the most senior professor. Therefore, my first priority will be to provide a decent standard of living for all those who serve the institution.

My second priority will be to work very hard on the improvement of the quality of student life: This is a topic that is highly complex, and I hope to discuss it another time. Let me simply say that this is one area in which there is still a great deal to be done until we can rest in peace knowing that we have really done all we can to improve life on the campus.

Third priority, of course, goes to the continual improvement of the quality of the educational program. We live in an age of rapid change. It is a constant challenge for Dartmouth, and similar institutions, as to how they can retain the best of their traditions and yet respond to the need for change.

Fourth and finally there are needs for physical facilities in order to implement the other priorities, both to enable educational programs to grow and to help improve student life.

Once a new president states such priorities, he cannot help asking himself whether the institution has the necessary financial resources to implement them. I have worked very hard in the past five weeks to try to reassure myself on that topic. We are nearing the end of a highly successful capital fund drive, and I have no doubt at all in my mind that this drive will go over the original goal set for it. I have no doubt in my mind that our alumni, who have been exceedingly generous with their support in the past, will continue to be so. Therefore, I can say to you that we do have the necessary financial resources - but just barely.

And it is here that perhaps the greatest challenge to the institution will come. We must be willing to make difficult - I will even say occasionally painful - decisions in order to be able to mount progress for the institution and yet at the same time live within the limitations of our financial resources.

We cannot proliferate new programs indefinitely without destroying the institution. No matter how attractive the suggestions may be, we cannot be all things to all people. We must, of course, consider new programs because this is an age of change. We have set a course for the establishment of Ph.D. programs which is only half complete - with the humanities and most of the social sciences still left out. And yet, as we consider new Ph.D. programs, we must be willing to reconsider the existing programs, as we must be willing to reconsider all programs, to ask whether the goals for which they were set up are still of paramount importance to the institution and whether those specific programs are really better than others that may be substituted for them. Similarly, as we work for new undergraduate programs, we must ask whether, to make room for these, it is possible to reduce some existing program or even to eliminate one here or there, not necessarily because it is bad but because one must make room for newer and more urgent needs. In short, I hope that we can pledge that no existing program is sacred, that there is none we are not willing to reconsider.

These are very difficult issues to decide, and therefore one of the fundamental problems that concerns me is how an institution like Dartmouth College can make such difficult and far-reaching decisions. Of course, it is part of the role of the president to play a leading part in the setting of institutional priorities. At the same time, I would find it intolerable if these priorities were imposed from above without the entire community sharing in the discussions and debates which lead to the setting of institutional priorities. It therefore will be my policy to make necessary facts widely available so that all segments of the community can share in the making of these difficult and perplexing decisions. I have already instituted measures that hopefully will improve the way our budget is presented publicly, so that it will not take quite as much of an expert to understand fully what is possible and what the limitations are upon our decisions. So much for the role of the president.

I feel that the faculty must bear a significant share of the burden of deciding the fundamental priorities of the institution, tution, and I have very reluctantly reached the conclusion that the present organization of the faculty is a serious hindrance toward carrying out this goal. The faculty is too fragmented; there are too many walls. Because there are too many fragments, it is difficult to provide the strong continuous leadership necessary for the decision-making process.

As I said in the beginning of my talk, we are one of the very few institutions that have the full breadth of the university and yet are small enough to work as a single com- munity. But our faculty is divided into four separate faculties and I find that intolerable. I feel that the time has come for Dartmouth to have a single faculty, organized into reasonable units with close and strong intellectual ties, with a continuity of strong leadership, with significant staff support for the chairmen of the various units, and with as few barriers as possible among them. Such a faculty could assume a truly major role in shaping the priorities of the institution.

I am not naive enough to believe that mere administrative reorganization will solve problems. But I am convinced that having an organization that does not meet the needs of today can be a very serious handicap in any effort towards the solution of problems and can prevent the solutions from occurring. As a matter of fact, at the very beginning of the reorganization, I am confronted with a constitutional dilemma in trying to bring about a single faculty for Dartmouth College: we seem to have no organ within the existing organization that could even sit down and talk about it. I am therefore appointing a presidential commission on the organization of the faculty which will be charged to work on these problems and which will be given up to twelve months to come in with constructive plans for the reorganization of the faculty.

lET me now turn to the role of the students. We, of course, all know the great dilemma that at the time when students are asking for more of a voice in the decision-making process the student body is so diverse and has such highly different motivations and interests that no student today is representative of the student body. Indeed, this is probably the reason that representative student government has essentially disappeared from this campus. Therefore it seems to me that one must look for new and imaginative approaches to enable students to participate in the great debate. First of all, I hope to open new avenues as well as use existing avenues to distribute as much of the necessary information to the student body as possible. At the very least the students should feel that they have been completely informed. Secondly, I hope that all agencies at the College involved in decision-making will invite student opinions, and that we will open channels through which students can be heard. And finally we must find the means, even though we don't have representative student government, for placing students on some key decision-making committees. I was very much encouraged by the imaginative article written by the chairman of one of our key committees and a member of the senior class in a recent Dartmouth Review. That article, I felt, had in it a number of suggestions that at least point the way toward having students involved on many more committees. I therefore urge the Committee on Operation and Policy and the Campus Conference to make it a high priority item for the next twelve months to work out a means by which students can participate in the decisionmaking process at Dartmouth and to find means by which students can have a feeling that they are fully informed and that their voices are being heard.

As long as I talk about the role of the student in decision-making, I must ask questions about the-nature of the student body. In thinking about this it occurred to me that perhaps the greatest change in the last half century in Ivy League universities has been the fact that there has been a great diversification of the composition of the student body. I see at least three major forces which have brought this about:

The first was the institution of a broad scholarship policy which enabled students to attend a major university irrespective of their families' financial situation.

The second great change came about as a result of the upgrading and improvement of secondary school education. Students with special talents and great motivation could work their way ahead of the class, come to college as advanced placement students, and be at least a year if not two years ahead of the other freshmen. This" actually presented a significant educational challenge to an institution that is predominantly an undergraduate institution, to make sure that we had sufficiently exciting intellectual undertakings for these students to keep them stimulated for a period of four years.

We are now faced with a third major force and a new challenge when Dartmouth College decided to admit students not only irrespective of their financial situation but even if society had deprived them of an opportunity to attend a first-rate secondary school. This is a new challenge to us and one for which we are not as well prepared. I feel that we have a great deal to learn about the education of disadvantaged students. We made some honest starts this year, some of which proved to be false starts, and we hope we will do a great deal better next year and hopefully even better the following year. But I want to say to you that although we must build a meaningful bridge between where secondary schools left students through no fault of their own and where Dartmouth hopes they can enter - it is not enough to build an educational bridge alone. Unless we can find the means to make these students feel a part of the Dartmouth family, we should not admit them in the first place. And this is the greatest challenge: we must somehow find the means whereby every student no matter what social background he comes from, once he is a student at Dartmouth, feels he is a full member of the entire community.

Not only do we have students with diverse backgrounds, but they come to us with a great diversity of goals that sometimes puzzles us. As a result of this, questions are continually raised about the meaning in general of a liberal arts education and in particular about the bachelor of arts degree.

I think I find it easier to say what to me the bachelor of arts degree should not be. It is not the mastering of a prescribed body of knowledge. Human knowledge is too vast and too complex to be able to cut out so many pieces of it and say this is what you must master. It is not thirty-six pounds of well-packaged education. It is not the accumulation of a grade-point average. At the other extreme, it is not the accumulation of a smattering of knowledge from all fields whose sole use is that the recipient of it can make occasional intelligent remarks at a cocktail party.

I have tried to think of a way of answering what a B.A. should mean in the year 1970, and here is a first attempt at it. It means to me four years spent at Dartmouth College in preparation for a meaningful life. At the end of the four years, we certify that the student has made the most of his opportunities at Dartmouth. This should certainly include the acquisition of an appreciation of the totality of human knowledge. It should at some point include a concentrated effort, in an area of the student's own choice, which will stretch his intellect to its ultimate limit. And above all, it should include the chance to work out one's own values and arrive at a meaningful goal for life.

As we have diversity of students and diversity of goals, We must have diversity of means. First and foremost the university is the guardian of civilization and the guardian of human knowledge. We must therefore provide the opportunity and the peace of mind necessary for scholars to' carry out their scholarship and research. Some students who wish to follow in these paths and elect traditional professions will therefore find the normal majors provided by professionals as the most stimulating part and the most significant part of their undergraduate education. Still others will find that it is active participation in the creative arts that provides the road to a rich life of fulfillment.

To me, the great challenge is somehow to allow each student to find his own way of preparing himself for life. I was extremely pleased to hear that our Committee on Educational Planning is even now working on means to open up more freedom for students to work out their own educational programs, and I urge them during the next twelve months to come with their recommendations to the faculty.

I must say one more thing about the present generation of students. While I have the greatest admiration for the genuine dedication they have for solving the problems of society, I also have a deep-lying worry of turning out a generation of students who have all the best motivations and are totally untrained to do anything about the problems of society.

It is therefore my personal feeling that it should not be the destiny of Dartmouth College to be the actual agent for the solution of the problems of society, but rather it is the role of this institution to train the future leaders who will solve these problems. It should train leaders who will enlarge human knowledge, leaders who will work in high office, leaders who will guide great corporations to new services to society, leaders who will work to wipe out poverty and disease, and I hope leaders who will lead their people out of the ghettos.

When I speak of this great diversity of students, I must pause for one moment, to note a peculiarity. Dartmouth College, which has such a superb record in the admission of all minorities, does not today consider for admission a majority of high school seniors.

It is my personal opinion that if we were refounding Dartmouth College today, we would, of course, not discriminate on the basis of race or religion. But I believe that if we were refounding the institution today, we would also not discriminate on the basis of sex.

It is therefore the dilemma of this institution, as it is of some of our sister institutions, that we have a 200-year tradition - which I can only describe as extremely male - with given facilities, given resources, and given styles of life. As you may have read in the papers recently, one of our sister institutions has discovered that the grafting on of a feminine component to an all-male institution carries with it some problems of its own. And yet, although there are many problems that I can foresee and that we have talked about earlier this year, I have a deep conviction that some-how solving this problem is one of the great secrets of improving the quality of life on campus. I therefore say that while we may not at this moment know the solution, we need an imaginative new approach that perhaps is even now being worked out. We may have to try avenues that have not been tried before, but I feel resolving the question of coeducation is one of our most urgent tasks.

I have tried to indicate to you that there are many major questions facing us. I for one welcome this challenge. I ask that we dedicate the next twelve months as a year of faraching debate and institution-wide soul searching. Let us freely discuss what our educational priorities should be and ponder the quality of life on campus. As my contribution to this debate, I will urge all segments of the community to take part. I will urge existing agencies on to greater effort. I will help to create new forums for discussion and debate. I will provide the information that you will need to keep the debate within the realm of reason, within that which is possible, but I will fight to prevent institutional inertia from stalling the debate.

I have the greatest hopes for a year of such wide-ranging debate, and yet I must issue a warning. During this year, you will hear the voices of those who have lost faith in man's ability to improve his institutions. You will be told that the road to change is through confusion, through confrontation, and through coercion. These are the voices of doom. Do not listen to them. If we can avoid the traps that these voices present, you have my solemn promise that in a year of peaceful and constructive debate we can bring about decisive change.

Dartmouth College is beginning a new century in its history. I am offering you an opportunity to work together to reconsider the fundamental nature of the university. Let us act for the next twelve months so that historians may some day record that a small college in the North Country played a significant role in opening a great new era for higher education.

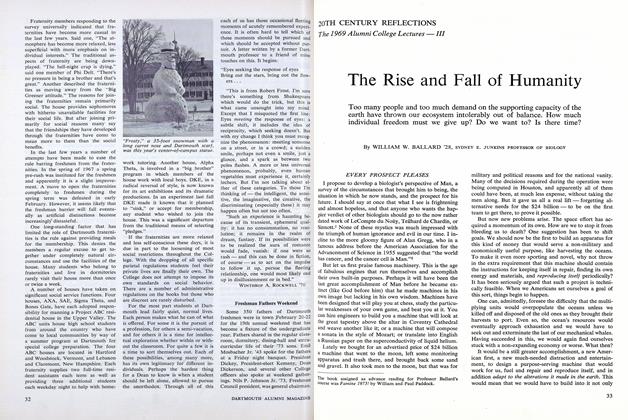

The Wentworth Bowl, symbol of the Dartmouth presidency,is passed from John Dickey to John Kemeny at March 1ceremony. The Flude Medal worn by President kemenywas also presented to him as a symbol of office.

Further coverage of the inaugural ceremony, with texts andPhotos, will appear in next month's issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Rise and Fall of Humanity

March 1970 By WILLIAM W. BALLARD '28, -

Feature

FeatureTHE DICKEY ADMINISTRATION ENDS BUT NOT ITS PERVADING IMPRINT

March 1970 -

Article

ArticleThree Students Argue for Coeducation

March 1970 By CHERYL CAREY, Coed, RANDY PHERSON '71, RICHARD ZUCKERMAN '72 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '7O -

Article

ArticleAn Antidote to Hugeness

March 1970 By CARLOS H. BAKER '32 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1970 By EDMUND H. BOOTH, DONALD L. BARR

Features

-

Feature

FeatureImpacts simply positive

MAY 1982 -

Feature

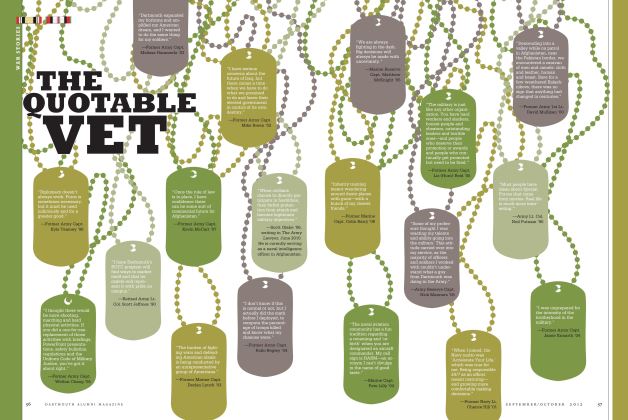

FeatureThe Quotable Vet

Sep - Oct -

Cover Story

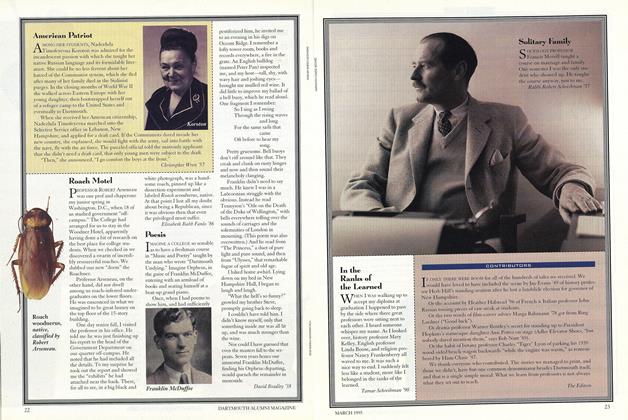

Cover StoryAmerican Patriot

MARCH 1995 By Christopher Wren '57 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO IMPROVE YOUR VISION NATURALLY

Sept/Oct 2001 By GLEN SWARTWOUT '78 -

Feature

FeatureChange and Challenge

JULY 1965 By HAROLD KING DAVISON '15 -

Feature

FeatureChanging Values in College

JANUARY 1959 By PHILIP E. JACOB