THE FIFTY-YEAR ADDRESS

MORITURI TE SALUTAMUS, Mr. President. While these 1920 gladiators may not be fixing for a fight, and even though we may be looking over the abyss, we are very much alive to the issues facing the Dartmouth of today. We share as much in the Dartmouth fellowship and, indeed, in the conflicts as do the graduates of this day.

Dartmouth 1920 has the unique distinction of being the first 50-year class formally to welcome John Kemeny as the President of the College. While we came first, to be admitted and admonished, instructed and inspired by the College that then was, you came as President to the College that now is, to be concerned and confronted with the complexities of students of this strange generation beset with impulses and motives we of an older generation do not, and sometimes do not really try to, understand.

One of the world's great musicians for whom I have an old affection is Artur Rubinstein. Recently he was asked by a young student what he thought of modern music. "I do not understand it," he replied, "and what I do not understand I cannot explain." We, the seventy-year-old remnants of the class that left this campus fifty years ago now look at the College and try to relate every aspect of it to the College of our experience. The conclusion becomes inescapable that to know this Dartmouth we must know the student. What is at the heart of the matter, the compulsions and the motivations, and hopefully the solutions that lead him, and us along with him, out of the morass and bewilderment to a rationale that enables him to live better with himself?

Mr. President, we are privileged to tell you of the respect we have for your accomplishments; of the high hopes we have for the College under your leadership; of the undying affection of the alumni body of which we are only a fragment, and of the concern we have for the preservation of the Dartmouth identity, and what that means each one of us will have to define in his own terms.

To most of us, I think, it means maintaining the vigor and something of the homeliness of the instruction of Eleazar Wheelock: preserving the spiritual force of Dr. Tucker in the life of the contemporary campus; applying the wisdom and that discerning evaluation of the opportunity that Ernest Martin Hopkins saw in the Dartmouth of his day; understanding the comprehensiveness of mind and relentlessness of purpose of John Dickey. The pedestals on which these men stood compose the traditions and heritage of the College, and they ought not to be unreasonably demolished.

Dartmouth 1920 came to Hanover in sultry September of 1916. We were the first class to matriculate in that first year of Dr. Hopkins' presidency. I arrived in Hanover in a Model T Ford driven by my grandfather, a Baptist preacher on his way to a meeting. I was deposited with an old steamer trunk in front of College Hall, and abandoned, without ever having seen the place or knowing a soul, and without the formality of having made an application for admission. Directed to the Ad Building, I produced my credentials from high school and was summarily admitted. I quiver at the jaundiced eye which Eddie Chamberlain would cast upon such preposterous effrontery today.

The recollection of those years crowd in upon each one of us. Few can here be recalled. The uncanny ability of misanthropic sophomores to make life miserable for our race of manifestly superior pea-green freshmen. The hikes in the hills and the shouts of "Coxey's Army" coming from the Deke House piazza as we weary outing-clubbers struggled up West Wheelock Street. The utter magnificence of the strawberry shortcake manufactured as only Doc Griggs could make it. Not only was he a great teacher, but who could have had the company of Leland Griggs without learning to respect and to love the land, the woods and the streams from which he could always conjure as fine a string of squaretails as ever went into a frypan?

Who is there with soul so dead as not to remember Doc Bowler's smut class? He it was who introduced us to some of the mysteries of the human body, male edition, and who raised a son who as surgeon, teacher and a founder of the Hitchcock Clinic scaled the summits of his profession. You got with it, yelling your head off at the sleight-of-hand of Jack Cannell and the chicanery of Pat Holbrook and Zack Jordan. We were famous for great inventions: the flying tackle of the immovable Gus Sonnenberg; Newton's laws of prestidigitation. There were the records, celebrated in their day, set by Tommy Thomson and Laddy Myers and made by the simple process of trying harder. There were records we should have envied more thany many of us did - those of the scholars, the brains "of 1920: Al Frey, Did Pearson, Phil Gross, Amsden and Dudley, and their select company.

At the Sesqui-centennial we turned out for Dartmouth Night, and some of us ate roast pig at Moose Mountain, and in Webster Hall listened to the anniversary ode, to the felicitations of Hike Newell, Governor Bartlett, Yale's Dean Jones, and to Hoppy's epilogue. The College was then 150 years old; it is 200 years old now.

If we were asked what experience came from the life on this campus that changed our perspective, that provided a sense of direction, that altered our course, our conduct and our attitude toward this country and to each other, each of us would have an answer and each one would be his own. For myself it would relate to great teachers — to Griggs, to Curtis Hidden Page, to Charles Haskins and Jim Richardson, to Francis Lane Childs and, especially, to W.K. Stewart who exposed you to arch-heresy and left you to escape from it as best you could.

This was the Hopkins era, and it created for us and for the generations of Dartmouth men whom he matriculated an understanding of the purpose of the liberal arts college. A little over twelve years ago on the occasion of honoring him at an alumni national dinner in New York, I brought to mind an instance of the adroitness of the Hopkins mind. When a member of the faculty criticized the decision by Judge Webster Thayer, a Dartmouth alumnus incidentally, in the Sacco-Vanzetti Case in 1921, an irate alumnus offered Hopkins $50,000 if he would fire him. Hopkins told the professor, "Now don't get excited. If you quit, I will too, and we will split the $50,000."

"Hoppy's greatest gift to Dartmouth is an indefinable legacy. It was he who made the Dartmouth fellowship the most contagious and flourishing phenomenon in this generation of college men. It was he who fused an alumni body, and warmed its affections, and bent it long since to the task of underwriting year by year the broadening influence of Dartmouth College upon its day and age."

These few minutes can be given over to reminiscence and the recollections of Hoppy's and our day, but we are too well aware that they appear to have little relationship to this campus and this Dartmouth. I venture to say, Mr. President, that most of us would find it a difficult task to convey to you an appreciation of what this institution has meant to us in our lifetime. Just as difficult it is to tell you what we think of what is happening to it today. Dartmouth, in the measure that we became a part of it, and that it became a part of us, has preempted a place in our lives, provided a deep well of experience from which we have often refreshed and renewed ourselves, from which we have sought support and encouragement, and from which we have derived courage and inspiration to keep us on and upward, sometimes in the face of frustration and defeat.

And so, we have always wanted Dartmouth to be the best, to be administered by the best president in the land, to be sought by the best students in the country, to be taught by the best faculty that could be found, to be soundly and conservatively managed, to be liberal and intellectually expanding, and always to afford for every student an educational experience excelled by no institution in America. And this is the way we want it to continue to be. This purpose is shared by virtually every man who sometime left his footprints on this old campus.

What we see here may be less distinct, what we say here less articulate, but where I believe the center of gravity of opinion rests, these men of Dartmouth expect this college to move, and that, in moving, those who determine its policies will demolish some of even the most sacred traditions. This will wrench the hearts of many of us. How, for example, shall we adapt the cadence of Men of Dartmouth to Men andWomen of Dartmouth? Lest the old traditions fail. What traditions?

We are well aware that coeducation for Dartmouth poses the probability of reordering the structure of the College. We are conversant with the argument the President has made for its support. His mathematics is unassailable. Most of his premises we shall have to accept. And still, in the examination of alternatives relating to the composition of the student body, what evidence is there that there are not a sufficient number of top quality students who prefer to come to a men's college? Dartmouth has never gone with the drift of things without a reasoned self-persuasion. The College has sought the solution that best promoted the essential purposes of this institution of learning. If the conclusion and the course were unique, they were Dartmouth's. In our time, this college has never been thought of as any second-rate place of learning.

Dartmouth 1920 cannot be accused of having any prejudice about women. But being opposed to coeducation begins to be something like being opposed to motherhood, an institution that seems to be falling into some disrepute lately. When a woman can enter a hospital and, for the asking, rid herself legally of an unborn child, another old tradition begins to tumble down. So we face up to the inevitabilities of the new generation and the new Dartmouth. Accepting the fact that good men students benefit from the stimulation and competition of good female students, and that good male students are now seeking institutions that provide such social and intellectual opportunity, we are reduced to asking: Is there still a place for one superlatively good men's college, and cannot that college be Dartmouth?

For myself, that question has still to be answered. When I face the choice between Dartmouth declining and Dartmouth undying, I'll take coeducation. But most men of the College will want this issue sharpened up and clearer cut. Let's hope it may be, before the choice becomes irrevocable.

Neglect of other and more overriding issues indicate no unawareness of them. It is not so good a time to lecture students. It is a time to try to understand them. But were I a teacher (and I am not without having served some apprenticeship in the art), I should try to put the weight of my experience behind the proposition that the institution we call government is infinitely better than chaos or anarchy, and that curing the ills of what we have is likewise better than substituting for it a vacuous remedy. There are means of getting the government to do what you want provided there are a sufficient number who agree with you, and are willing to organize and work persistently, relentlessly and intelligently to attain it. The chief ingredient of success is not noise, but work.

This is an imperfect government of the majority. Slowly, agonizingly, it is being perfected within the capabilities of a people practicing the art of the possible. Liberty, and equality, still so painfully being born, are put on the political auction block when the loyalty of the people is lost. We shall need the strength of that loyalty, as we need it now, and these boys and girls on today's campus will need it for whatever course they may elect to pursue for this nation and for themselves.

For Dartmouth men of our generation, a hard lesson we have to learn is that the loyalties are different; the focus of allegiance has moved. What the traditions and heritage of the College meant to us may mean little to most of the faculty on campus today. Their loyalties are to their profession and their professional attainments, to research and to their publications, to the business of learning and teaching. That is where their loyalties belong. And yet there has been something more to a Dartmouth education than learning, and that nebulous something has made all the difference. This has been the Dartmouth identity. Among the hopes we of this class hold for this college, Mr. President, is the yearning that you keep alive and meaningful that identity. For succeeding generations of Dartmouth students we want nothing quite so much as the opportunity for them to share in the richness of the experience we have enjoyed and which has added so much to the fullness of our lives.

In Robert Frost's Reluctance he closes, as I shall do, with these lines.

Ah, when to the heart of man Was it ever less than a treason To go with the drift of things, To yield with a grace to reason, And bow and accept the end Of a love or a season?

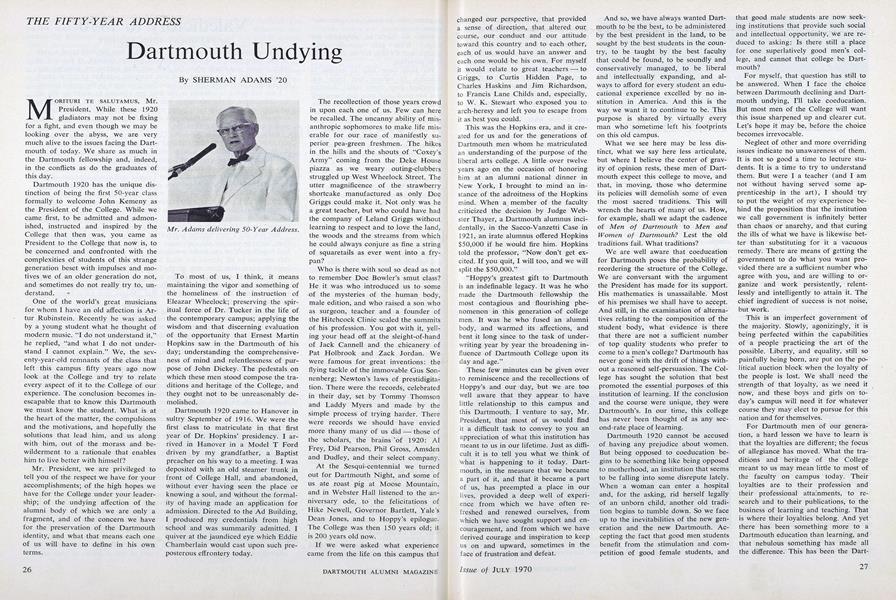

Mr. Adams delivering 50-Year Address.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHYBRIS AND SOPHROSYNE

July 1970 By WILLIAM AYRES ARROW SMITH, LITT.D. '70 -

Feature

FeatureDero A. Saunders '35 Elected President of Alumni Council

July 1970 -

Feature

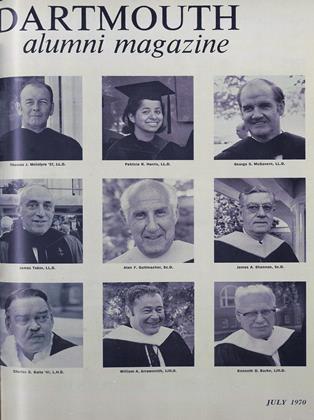

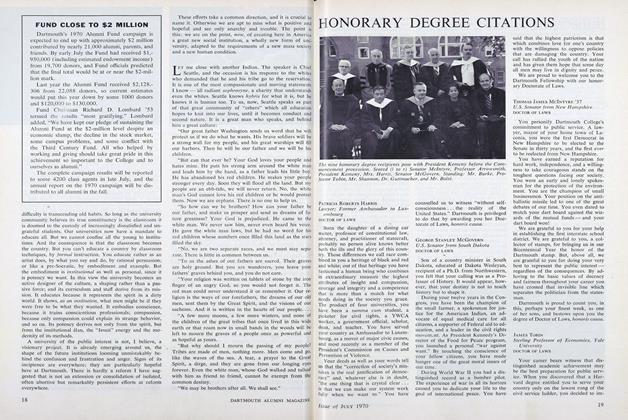

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1970 -

Feature

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

July 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

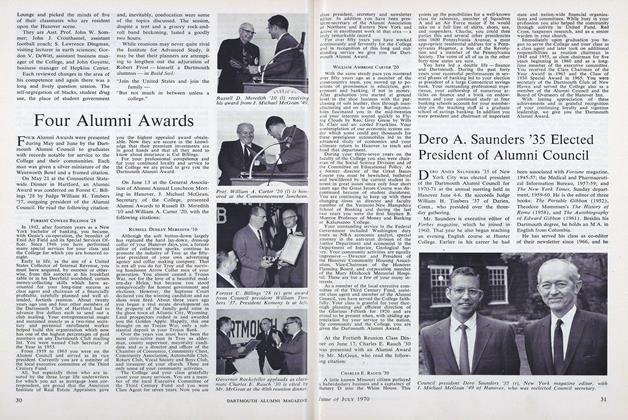

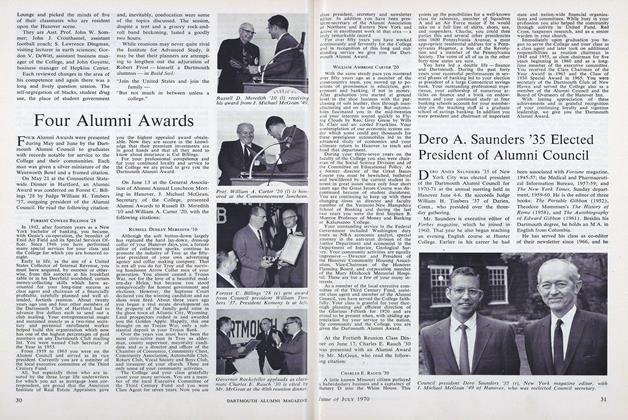

FeatureFour Alumni Awards

July 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1970 By CRAIG JOYCE '70

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1966

JULY 1966 -

Cover Story

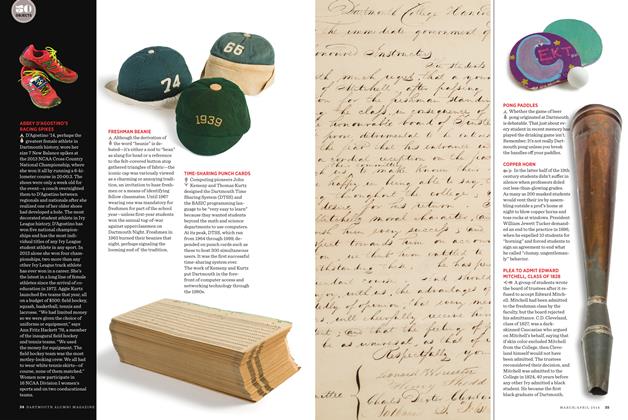

Cover StoryTIME-SHARING PUNCH CARDS

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May/June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

FEATURES

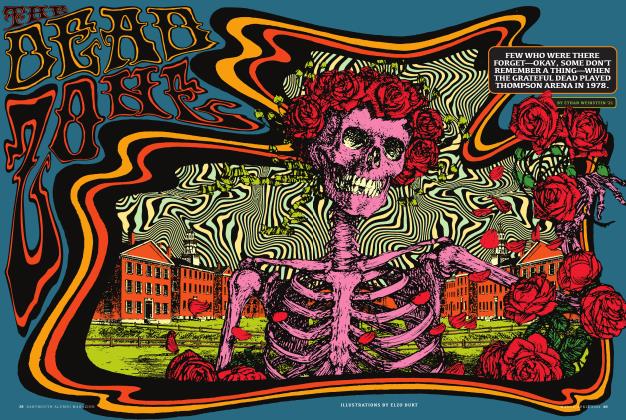

FEATURESThe Dead Zone

MARCH | APRIL 2022 By ETHAN WEINSTEIN '21 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Invented Dog Running

June 1989 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

FeatureJournal of a Long Season

March 1974 By TOM EGGLESTON