Prof.Henry L. Roberts (History). New York:A. A. Knopf, Inc., 1970. 332 pp. $6.95.

To publish or perish isn't the only option open to an astute academician. He can republish old essays behind new boards, thus build his bibliography, and survive very well. Henry L. Roberts of Dartmouth has done this in a collection of Eastern European studies published in scholarly journals over the last two decades. Historians, as well as all serious students of foreign affairs, may be grateful that he has done so.

One is struck first by his modesty. At. a time when any ten-day visitor to Moscow may put out a shingle as a Kremlinologist, the distinguished former director of Columbia's Russian Institute and Institute on East Central Europe is candid enough to admit astonishment at Khruschev's sudden ouster, and to disdain all retroactive readjustments of his old (and sometimes faulty) insights: "Over the years I have become increasingly reluctant to play the Sovietologist (I never aspired to Kremlinology)," he explains disarmingly, "or to be an international ambulance chaser. This is partly a matter of temperament, but in my work as a bibliographer I have been struck by the disconcerting transience of most such endeavors."

As for the temptation to revise former views, he adds: "... I found in reviewing these pieces, that I simply could not tinker with them seriously. My present intellectual stance is not identical with the one I had five, ten or twenty years ago. If I am not to start anew, they must appear as conceived, warts and all."

The warts are minor. Even where Roberts misjudged the trend of events his careful, onion-skin dissection of men and their times wears very well indeed. He follows that soundest rule of a good reporter to beware of finding what he is looking for, is constantly peeling off the good reasons to find the real ones, and brings out in masterful elaboration of detail and motive the complex nuances behind seemingly simple events and policies.

This quality in Roberts is seen at its best in his study of Maxim Litvinov, in the decade of his verbal showdowns with the Fascist aggressors in the League of Nations, when he became the hero of a whole generation of idealistic anti-fascists who saw him as a sort of Jewish Gary Cooper stalking the Nazi blackhats in an eternal High Noon (who can forget his magnificent, merciless dissection of the Hoare-Laval hypocrisy over "non-intervention" in bleeding Spain: "Non-sense, even when repeated three times by parrots, is nonetheless nonsense"?).

With all hypnotic fascination of a mystery writer piecing together fragments of clues, Roberts hunts for the "real" Litvinov, and the "real" Soviet policy, behind the facade of Litninov's "permanent trademark [of] unrevolutionary reasonableness," his endless demands for "complete disarmament" as a sure-cure preventive for war, his eloquent promises of Soviet support for the Czechs if France would also move under their joint pact. Whether either Litinov or the Soviets ever intended actually to aid the Czechs, Roberts cannot fully answer, but leaves a preponderant doubt: Litvinov's constant reminders that France must act first, and also obtain Polish and/or Rumanian permission for Soviet troops to pass through; his 1939 prophecy to Britain's Sir William Seeds that Hitler would attack Britain before the U.S.S.R. and "to succeed he will prefer to reach an understanding with the U.S.S.R."

Roberts is equally absorbing in his discussion of the labyrinthian motivations and corkscrew turnings of Balkan politics and policies. These small states, like the whetstone before the wheel of Great Powers on all sides, must always bear in mind the aphorism: "We have three kinds of friends, our friends, our friends' friends, and our enemies' enemies," as well as the Cypriot saying: "When the rock falls on the egg—alas for the egg! When the egg falls on the rock—alas for the egg!" Roberts notes that this makes Balkan leaders adept at "what is called, in alpinism, 'chimneying': working one's way up a crevice between two opposing cliffs by wedging oneself between both sides." When single-minded Americans were hailing the Soviet triumph over brutal Nazism, realistic Balkan leaders were steeling themselves against Soviet brutality to come.

The difficulty that such apprehensions place upon ever building adequate pacts of mutual protection is traced by Roberts in his detailed study of how all such efforts, like the Little Entente between Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Rumania (later linked with France) inevitably came to grief. They could find no common determination on meeting threats from great powers, because each was afraid of a different one: Czecho-slovakia of Germany, Rumania of Russia, Yugoslavia of Italy. Similarly the Balkan Entente—Yugoslavia, Greece, Turkey and Rumania—had to omit irridentist Bulgaria, and provided for mutual defense "against a Balkan aggressor only, and not a great power." As in some macabre quadrille, each advanced to its inexorable doom, prevented, like so many sleepwalkers, from acting to save one another.

This difficulty of discovering real interests as distinguished from emotion, ideology or theology (including Marx), is not confined to the Balkans. The "two atomic colossi . . . doomed malevolently to eye each other indefinitely across a trembling world" (in Eisenhower's words) still see each another through the distorting lenses bequeathed them by Wilson and Lenin, "neither of whom knew much about the other's country," with the result that "Russian-American relations since that time—in addition to all the real differences between the two powers—have displayed the peculiar quality of two people talking past one another." This results in a "strange failure of communication, not verbal or semantic, but in basic principles."

In the case of both Wilson and Lenin we feel that their view of diplomacy and world politics was a projection of domestic considerations outward upon the international scene. The very universality of their prescriptions for a world order betrayed a parochial origin.

This parochialism persists today, says Roberts in his chapter on "Soviet-American Relations," in three persistent fallacies in making our national policy decisions: "the failure to think in context, the oversimplification of the problem, and the demand for omniscience and omnipotence." Illustrating the penchant for "tentative hypothesis," he cites a recent "suggestion to study the requirements of American policy over the next decade under two differing assumptions: (a) that the Soviet regime remained strong and cohesive, (b) that the Soviet regime suffered internal strains and disintegration. Unfortunately, most of the problem lies precisely in these assumptions, and it is evident that the answers resulting from such a study would be of little use."

Approaches which might be of considerable use are spelled out by Roberts in wise, realistic, hard-headed detail, which the present planners of Foggy Bottom would do well to study carefully.

Now a business associate of Ralph Lazarus'35, the Dartmouth Trustee, Mr. Miller, aformer chief editorial writer of the New York Herald Tribune, covered World War IIin Europe for the Cleveland Press.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

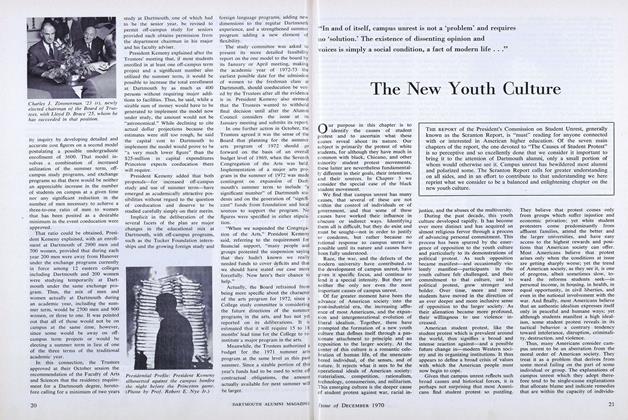

FeatureThe New Youth Culture

December 1970 -

Feature

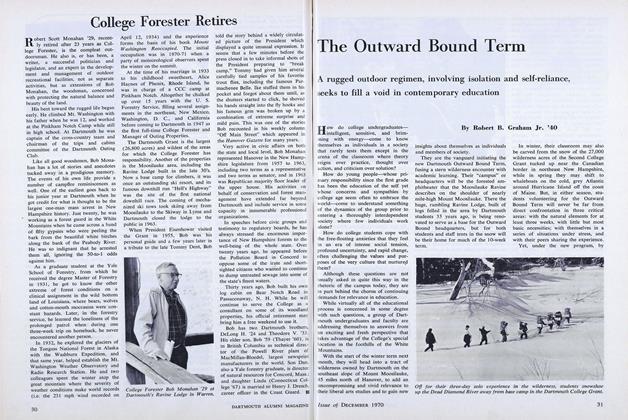

FeatureThe Outward Bound Term

December 1970 By Robert B. Graham Jr. '40 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Reenact 1770 Board Meeting

December 1970 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1970 By CHRISTOPHER CROSBY '71

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

January 1922 -

Books

BooksA SALESMAN TAKES AN INTEREST.

April 1953 By Albert W. Frey '20 -

Books

BooksMEXICO:

February 1945 By F.Cudworth Flint. -

Books

BooksA SHORT HISTORY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE, VOL. 1: FOUNDATIONS OF AMERICAN LITERATURE,

January 1952 By H. G. R. -

Books

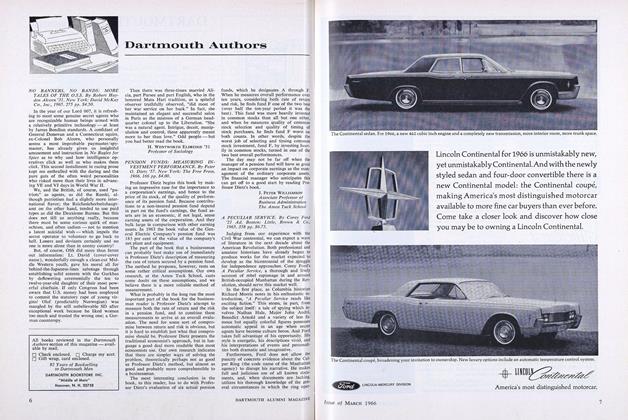

BooksA PECULIAR SERVICE.

MARCH 1966 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55 -

Books

BooksOF A HUNTER, NOW!

May 1945 By Vernon Hall Jr.