He is, without question, a major figure in the landscape. And this holds true whether one considers the landscape to be that of his profession and art, or that of his day-to-day life. Meeting him is an experience one is not likely to forget; and by "meeting him" one means an encounter with his films as well as an encounter face-to-face. As more than one student has already told me: he's a fascinating man.

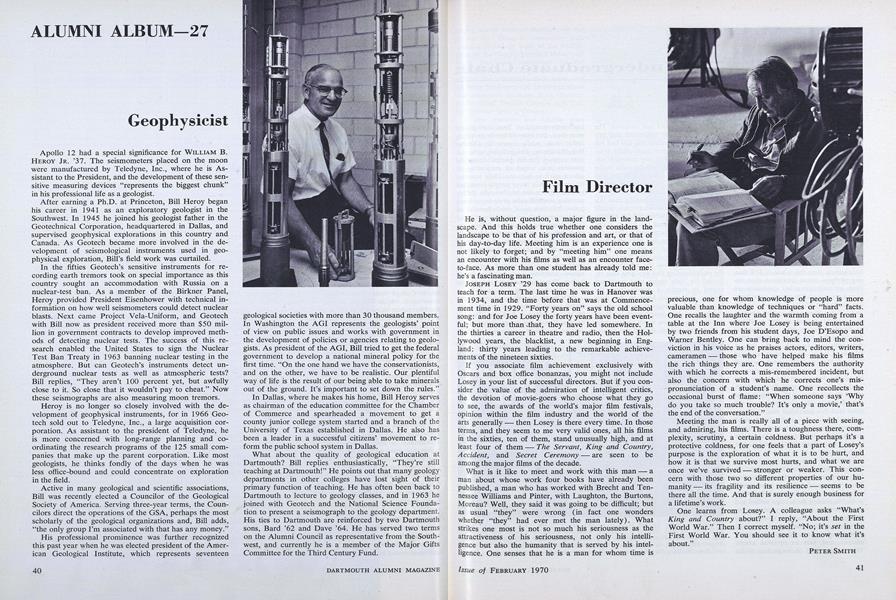

JOSEPH LOSEY '29 has come back to Dartmouth to teach for a term. The last time he was in Hanover was in 1934, and the time before that was at Commencement time in 1929. "Forty years on" says the old school song: and for Joe Losey the forty years have been eventful; but more than,that, they have led somewhere. In the thirties a career in theatre and radio, then the Hollywood years, the blacklist, a new beginning in England: thirty years leading to the remarkable achievements of the nineteen sixties.

If you associate film achievement exclusively with Oscars and box office bonanzas, you might not include Losey in your list of successful directors. But if you consider the value of the admiration of intelligent critics, the devotion of movie-goers who choose what they go to see, the awards of the world's major film festivals, opinion within the film industry and the world of the arts generally - then Losey is there every time. In those terms, and they seem to me very valid ones, all his films in the sixties, ten of them, stand unusually high, and at least four of them - The Servant, King and Country,Accident, and Secret Ceremony - are seen to be among the major films of the decade.

What is it like to meet and work with this man - a man about whose work four books have already been published, a man who has worked with Brecht and Tennessee Williams and Pinter, with Laughton, the Burtons, Moreau? Well, they said it was going to be difficult; but as usual "they" were wrong (in fact one wonders whether "they" had ever met the man lately). What strikes one most is not so much his seriousness as the attractiveness of his seriousness, not only his intelligence but also the humanity that is served by his intelligence. One senses that he is a man for whom time is precious, one for whom knowledge of people is more valuable than knowledge of techniques or "hard" facts. One recalls the laughter and the warmth coming from a table at the Inn where Joe Losey is being entertained by two friends from his student days, Joe D'Esopo and Warner Bentley. One can bring back to mind the conviction in his voice as he praises actors, editors, writers, cameramen - those who have helped make his films the rich things they are. One remembers the authority with which he corrects a mis-remembered incident, but also the concern with which he corrects one's mispronunciation of a student's name. One recollects the occasional burst of flame: "When someone says 'Why do you take so much trouble? It's only a movie,' that's the end of the conversation."

Meeting the man is really all of a piece with seeing, and admiring, his films. There is a toughness there, complexity, scrutiny, a certain coldness. But perhaps it's a protective coldness, for one feels that a part of Losey's purpose is the exploration of what it is to be hurt, and how it is that we survive most hurts, and what we are once we've survived - stronger or weaker. This concern with those two so different properties of our humanity - its fragility and its resilience - seems to be there all the time. And that is surely enough business for a lifetime's work.

One learns from Losey. A colleague asks "What's King and Country about?" I reply, "About the First World War." Then I correct myself. "No; it's set in the First World War. You should see it to know what it's about."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom the Primate Patrimony To the Fellowship of Flowers

February 1970 By JAMES W. FERNANDEZ, -

Feature

FeatureThe Pros and Cons of Coeducation

February 1970 -

Feature

FeatureSpeaking of Books

February 1970 By FRANCIS BROWN '25, -

Feature

FeaturePROF. JOHN G. KEMENY CHOSEN AS DARTMOUTH'S 13TH PRESIDENT

February 1970 -

Article

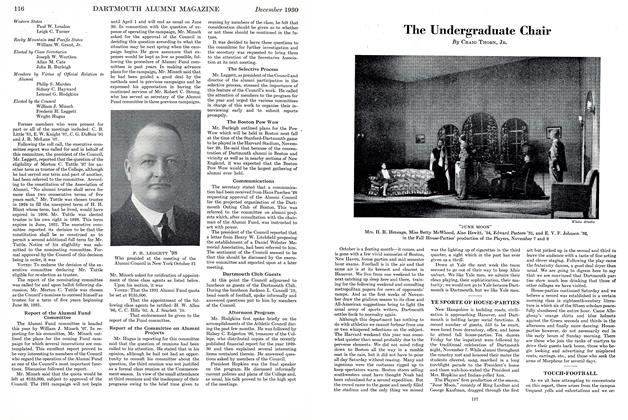

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1970 By EDMUND H. BOOTH, DONALD L. BARR

PETER SMITH

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

November 1979 -

Article

ArticleCaution: Explosive Device

NOVEMBER 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleAlms for Blissful Calm

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksAttentive Eye, Attentive Ear

November 1983 By Peter Smith -

Books

Books"One Man in His Time..."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksHow Much Freedom?

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith

Article

-

Article

ArticleDeath of "Major" Ballou

August, 1911 -

Article

Article1942 Fund Passes $75,000

June 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Way It Was

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleThe Nano Brewer

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Juliette Rossant ’81 -

Article

ArticleTOUCH-FOOTBALL

DECEMBER 1930 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleTuck School

February 1951 By H. L. Duncombe, JR.