"It is, sir, an exceptional seat . . ."

"Sit isn't just hype," said my friend. I told him that it was by no means just hype, and tried to assure him that, indeed, the most important things about it were impervious to hype. Most of all, I needed to make him understand the great mistake of allowing his skepticism about extravagant claims to deprive him of the chance to enjoy it, and benefit from it, and be made better by it.

The six-fold "it" in the first paragraph is the Royal Shakespeare Company's stage adaptation of The Life and Adventures ofNicholas Nickleby. That production is not the subject of this column, for I am sorry to say that I simply do not know how to write well enough to tell my admiration for it as I would want it told. In any case, it's hard to see how the production itself, 500 minutes of total theater and utter delight, can be made to assume any relevancy to Dartmouth College and the purposes of its alumni magazine. The hype about the production, though, is another matter.

One cannot help wondering how Dickens would have written about the American treatment of this production. It would be a good competition for one of our intellectual weeklies, if we had any, to invite readers to create an imaginary letter from Dickens to a friend or a couple of paragraphs from a new novel in which the hypers are dealt with as so many other carriers of the minor vices were dealt with, immortally, by the master himself. (One can assume that whatever else he might have done, Dickens would surely have drawn some attention to a phrase in the advertisements that gives us the apotheosis of the extravagant claim: "Every seat," the blurb says, "is exceptional." Just think about that for a moment.) More important, Dickens' reaction would have helped us see the hazards of hyperbole, the subject of this little essay.

One of the hazards was raised in my first sentence: A person who would love what is being hyped, who would appreciate it from top to bottom, may well never try it because of a distaste for the way it is hyped and a distrust for anything which the hypers give the full treatment to.

Just about as bad is what happens when people buy the hype rather than what is being hyped, and then end up with something they've never given any thought to and don't know what to do with. I'm told that in the early days of young Nickleby's run at the Plymouth Theatre it was not uncommon for people to leave during the performances or not to come back after intermissions. Frankly, I find this almost impossible to believe, so universally irresistible does this production seem to me to be. If such incredible goings-on did occur, the only explanation that I can think of for them is that those people simply went because they had been told "it" would be the experience of a lifetime and because they thought that the $100 tickets would somehow guarantee that it would be; but they went to the theater itself on their chosen day without the slightest idea of what "it" was that they were getting into. And they didn't like or couldn't understand or wouldn't yield.

Then there's the business of what the hype does to the hypers as well as to that which is hyped. Surely, it destroys some valuable part of them. Take the business of the $100 seats. It is true that every seat is worth $100 because you can see the stage from every seat, and what's on stage is at least $100-worth wonderful. But every seat is not exceptional (assuming that the phrase means anything at all). Perhaps it's more in the spirit of things to use an appropriately Orwellian turn of phrase and to say that some seats are more exceptional than others. In the process of finding their hyped-up phrase, the hypers have done something to the language, and they've told their nasty little lie in behalf of a show which doesn't in the least need it.

And what, you may ask, has all of this to do with Dartmouth any more than Mr. Lillyvick and Madame Mantalini and the Infant Phenomenon have? Well, there are a few who wonder whether some of us at the College aren't getting a bit carried away in our self-congratulation, aren't beginning to believe our own slogans a bit too readily. Periods of fund-raising campaigns are especially hazardous, it seems, for nobody wants to hear about doubts or dilemmas or intractable problems of the kind that money can't take care of. Nobody wants to dig too deeply at such a time for whatever truth may lie behind that old image we have to live with. The trouble is that while it's one good thing to rally round the flag, it's something else to run the flag so far up the pole into the sunlight that we can't see whether or not it's tattered. And what of the good students who don't apply because they don't trust extravagant claims, or those who come without knowing that the reality behind them is something they're not prepared for?

It isn't easy; nobody's saying it is. Any more than it can have been easy for the Nickleby importers. Even worse than the worst of the results of the hype would have been unbought seats for a show which so deserves to play to full houses. Given all that Dartmouth has to offer, of course, it would be a far greater crime to see its enrollments decline or its support fall away than to exaggerate its virtues. But somehow these hypers leave me wondering whether they really know just how good the things they're hyping are. Can't they see, we want to cry out, that it doesn't need their encomiums? Can.'t they see that it's so much better than anything they can say about it? Don't they know that it has only to be and the people who will love it will find it? Can't they forget their perfection-implying slogans?

One last thought strikes me as I write those words. Implying perfection is, for me at least, entirely excusable when it comes to The Life and Adventures of NicholasNickleby, for there are such things as perfect works of art, and if this production isn't one of them it surely comes mighty close. But perfect lives, alas, there are not; nor perfect institutions, either.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

December 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureAmerica's First Hostage Negotiator

December 1981 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeatureFirst Five Months

December 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

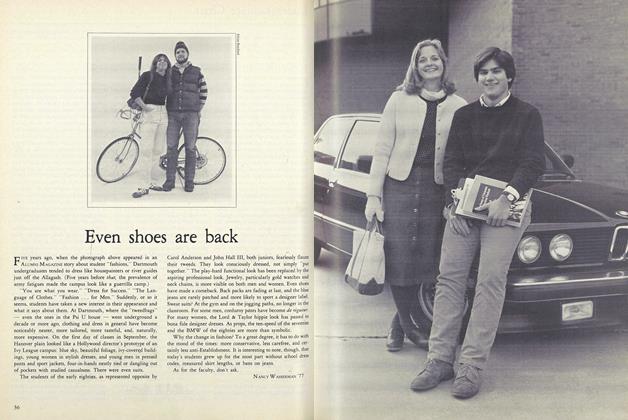

FeatureEven Shoes Are Back

December 1981 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleA Skeptic in Simian Clothing

December 1981 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Sports

SportsAn Unexpected Pleasure

December 1981 By Brad Hills '65

Peter Smith

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1980 -

Article

ArticleFilm Director

FEBRUARY 1970 By PETER SMITH -

Article

ArticleCaution: Explosive Device

NOVEMBER 1981 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksPeace and War

DECEMBER 1983 By Peter Smith -

Books

BooksWords of Wisdom

MAY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Books

Books"One Man in His Time..."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith