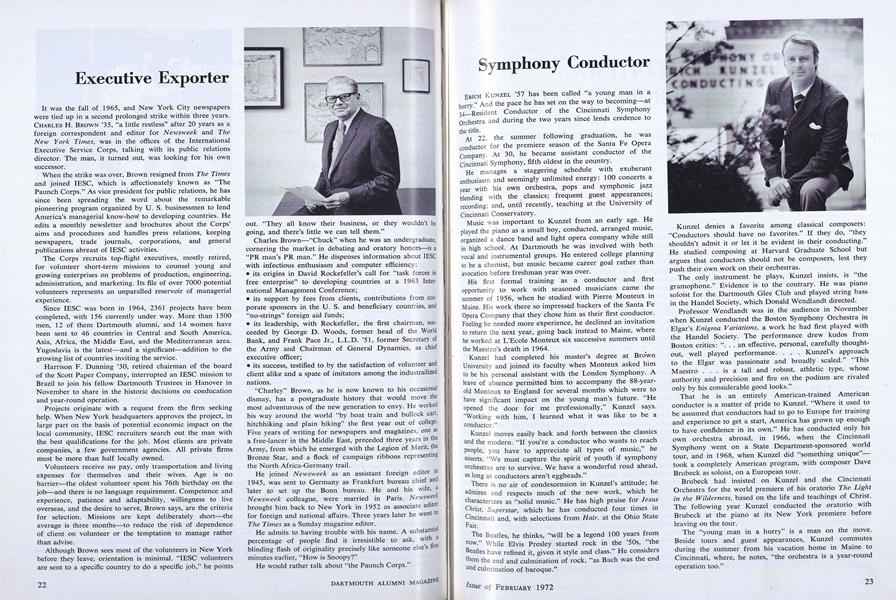

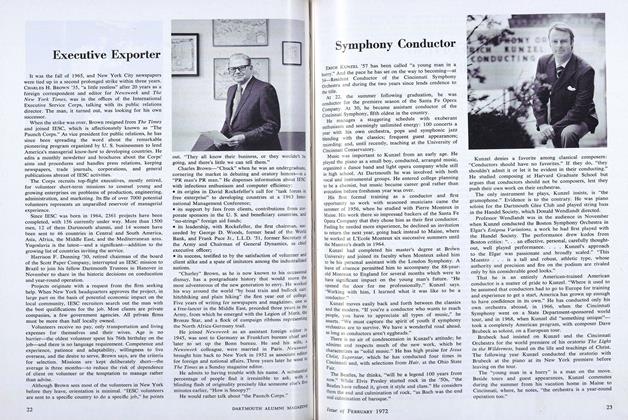

Erich Kunzel '57 has been called "a young man in a hurry." And the pace he has set on the way to becoming—at 34-Resident Conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and during the two years since lends credence to the title.

At 22, the summer following graduation, he was conductor for the premiere season of the Santa Fe Opera Company. At 30, he became assistant conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony, fifth oldest in the country.

He manages a staggering schedule with exuberant enthusiasm and seemingly unlimited energy: 100 concerts a year with his own orchestra, pops and symphonic jazz blending with the classics; frequent guest appearances; recording; and, until recently, teaching at the University of Cincinnati Conservatory.

Music was important to Kunzel from an early age. He played the piano as a small boy, conducted, arranged music, organized a dance band and light opera company while still in high school. At Dartmouth he was involved with both vocal and instrumental groups. He entered college planning to be a chemist, but music became career goal rather than avocation before freshman year was over.

His first formal training as a conductor and first opportunity to work with seasoned musicians came the summer of 1956, when he studied with Pierre Monteux in Maine. His work there so impressed backers of the Santa Fe Opera Company that they chose him as their first conductor. Feeling he needed more experience, he declined an invitation to return the next year, going back instead to Maine, where he worked at L'Ecole Monteux six successive summers until the Maestro's death in 1964.

KunzeS had completed his master's degree at Brown University and joined its faculty when Monteux asked him to be his personal assistant with the London Symphony. A leave of absence permitted "him to accompany the 88-year-old Monteux to England for several months which were to have significant impact on the young man's future. He opened the door for me professionally," Kunzel says. "Working with him, I learned what it was like to be a conductor."

Kunzel moves easily back and forth between the classics and the modern. "If you're a conductor who wants to reach people, you have to appreciate all types of music, he asserts. "We must capture the spirit of youth if symphony orchestras are to survive. We have a wonderful road ahead, as long as conductors aren't eggheads."

There is no air of condescension in Kunzel's attitude; he admires and respects much of the new work, which he characterizes as "solid music." He has high praise for JesusChrist, Superstar, which he has conducted four times in Cincinnati and, with selections from Hair, at the Ohio State Fair.

The Beatles, he thinks, "will be a legend 100 years from now." While Elvis Presley started rock in the '50s, ' the Beatles have refined it, given it style and class." He considers them the end and culmination of rock, "as Bach was the end and culmination of baroque."

Kunzel denies a favorite among classical composers: "Conductors should have no favorites." If they do, "they shouldn't admit it or let it be evident in their conducting." He studied composing at Harvard Graduate School but argues that conductors should not be composers, lest they push their own work on their orchestras.

The only instrument he plays, Kunzel insists, is the gramophone." Evidence is to the contrary. He was piano soloist for the Dartmouth Glee Club and played string bass in the Handel Society, which Donald Wendlandt directed.

Professor Wendlandt was in the audience in November when Kunzel conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Elgar's Enigma Variations, a work he had first played with the Handel Society. The performance drew kudos from Boston critics: "... an effective, personal, carefully thoughtout, well played performance.... Kunzel's approach to the Elgar was passionate and broadly scaled." This Maestro... is a tall and robust, athletic type, whose authority and precision and fire on the podium are rivaled only by his considerable good looks."

That he is an entirely American-trained American conductor is a matter of pride to Kunzel. Where it used to be assumed that conductors had to go to Europe for training and experience to get a start, America has grown up enough to have confidence in its own." He has conducted only his own orchestra abroad, in 1966, when the Cincinnati Symphony went on a State Department-sponsored world tour, and in 1968, when Kunzel did "something unique" - took a completely American program, with composer Dave Brubeck as soloist, on a European tour.

Brubeck had insisted on Kunzel and the Cincinnati Orchestra for the world premiere of his oratorio The Lightin the Wilderness, based on the life and teachings of Christ. The following year Kunzel conducted the oratorio with Brubeck at the piano at its New York premiere before leaving on the tour.

The "young man in a hurry" is a man on the move. Beside tours and guest appearances, Kunzel commutes during the summer from his vacation home in Maine to Cincinnati, where, he notes, "the orchestra is a year-round operation too."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

February 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

February 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

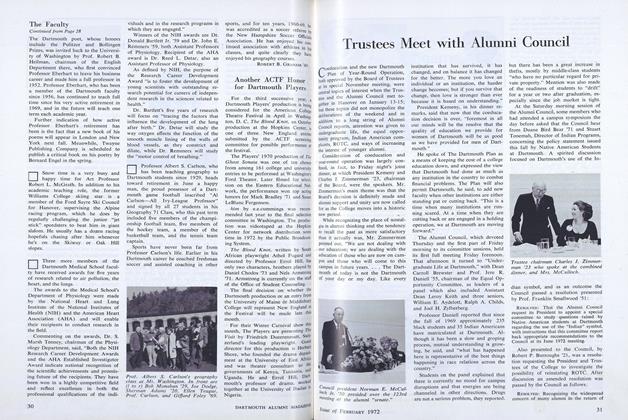

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureExecutive Exporter

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

February 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1972 By MARK HELLER '70

Features

-

Feature

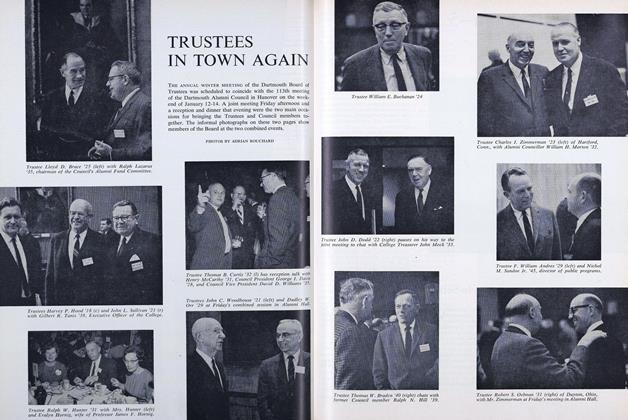

FeatureTRUSTEES IN TOWN AGAIN

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

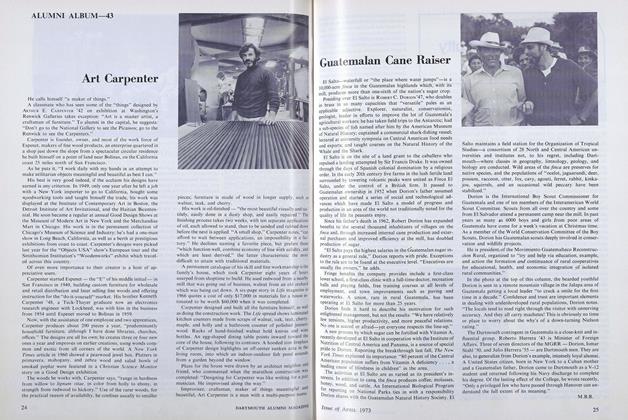

FeatureArt Carpenter

APRIL 1973 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1970

JULY 1970 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureFinancing Higher Education

MARCH 1972 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2012 By Llewelynn Fletcher ’99 -

Feature

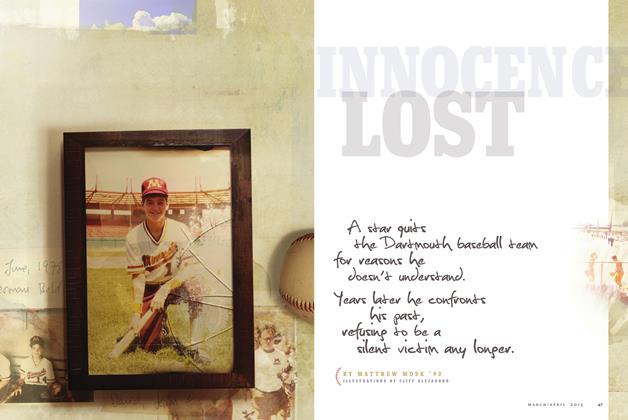

FeatureInnocence Lost

Mar/Apr 2013 By Matthew Mosk ’92