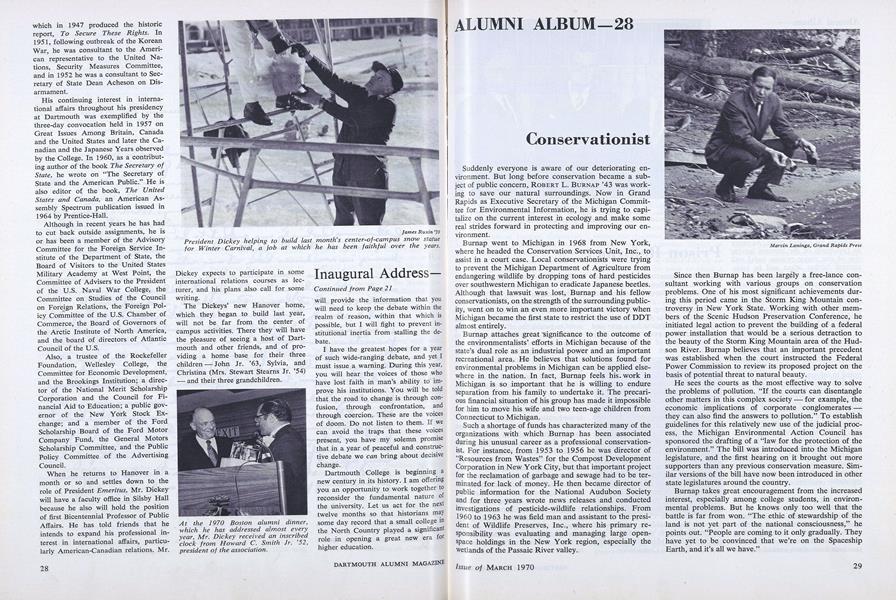

Suddenly everyone is aware of our deteriorating environment. But long before conservation became a subject of public concern, ROBERT L. BURNAP '43 was working to save our natural surroundings. Now in Grand Rapids as Executive Secretary of the Michigan Committee for Environmental Information, he is trying to capitalize on the current interest in ecology and make some real strides forward in protecting and improving our enviroment.

Burnap went to Michigan in 1968 from New York, where he headed the Conservation Services Unit, Inc., to assist in a court case. Local conservationists were trying to prevent the Michigan Department of Agriculture from endangering wildlife by dropping tons of hard pesticides over southwestern Michigan to eradicate Japanese beetles. Although that lawsuit was lost, Burnap and his fellow conservationists, on the strength of the surrounding publicity, went on to win an even more important victory when Michigan became the first state to restrict the use of DDT almost entirely.

Burnap attaches great "significance to the outcome of the environmentalists' efforts in Michigan because of the state's dual role as an industrial power and an important recreational area. He believes that solutions found for environmental problems in Michigan can be applied else-where in the nation. In fact, Burnap feels his. work in Michigan is so important that he is willing to endure separation from his family to undertake it. The precarious financial situation of his group has made it impossible for him to move his wife and two teen-age children from Connecticut to Michigan.

Such a shortage of funds has characterized many of the organizations with which Burnap has been associated during his unusual career as a professional conservationist. For instance, from 1953 to 1956 he was director of "Resources from Wastes" for the Compost Development Corporation in New York City, but that important project for the reclamation of garbage and sewage had to be terminated for lack of money. He then became director of public information for the National Audubon Society and for three years wrote news releases and conducted investigations of pesticide-wildlife relationships. From 1960 to 1963 he was field man and assistant to the president of Wildlife Preserves, Inc., where his primary responsibility was evaluating and managing large open-space holdings in the New York region, especially the wetlands of the Passaic River valley.

Since then Burnap has been largely a free-lance consultant working with various groups on conservation problems. One of his most significant achievements during this period came in the Storm King Mountain controversy in New York State. Working with other members of the Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference, he initiated legal action to prevent the building of a federal power installation that would be a serious detraction to the beauty of the Storm King Mountain area of the Hudson River. Burnap believes that an important precedent was established when the court instructed the Federal Power Commission to review its proposed project on the basis of potential threat to natural beauty.

He sees the courts as the most effective way to solve the problems of pollution. "If the courts can disentangle other matters in this complex society - for example, the economic implications of corporate conglomerates — they can also find the answers to pollution." To establish guidelines for this relatively new use of the judicial process, the Michigan Environmental Action Council has sponsored the drafting of a "law for the protection of the environment." The bill was introduced into the Michigan legislature, and the first hearing on it brought out more supporters than any previous conservation measure. Similar versions of the bill have now been introduced in other state legislatures around the country.

Burnap takes great encouragement from the increased interest, especially among college students, in environmental problems. But he knows only too well that the battle is far from won. "The ethic of stewardship of the land is not yet part of the national consciousness," he points out. "People are coming to it only gradually. They have yet to be convinced that we're on the Spaceship Earth, and it's all we have."

Marvin Laninga, Grand Rapids Press

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Rise and Fall of Humanity

March 1970 By WILLIAM W. BALLARD '28, -

Feature

FeatureTHE DICKEY ADMINISTRATION ENDS BUT NOT ITS PERVADING IMPRINT

March 1970 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Priorities for 1970

March 1970 -

Article

ArticleThree Students Argue for Coeducation

March 1970 By CHERYL CAREY, Coed, RANDY PHERSON '71, RICHARD ZUCKERMAN '72 -

Article

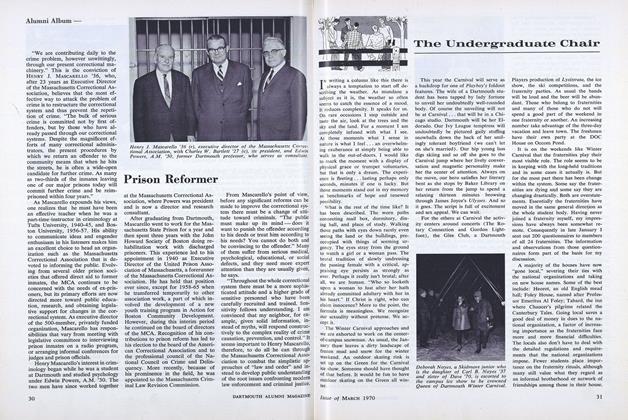

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '7O -

Article

ArticleAn Antidote to Hugeness

March 1970 By CARLOS H. BAKER '32

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

July 1919 -

Article

ArticleREPORT OF TRUSTEES' MEETING

October 1919 -

Article

ArticleEnglish Climbing Boys

November 1949 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleA Norse Appraisal

December 1945 By Johs. Johnson -

Article

ArticleVox

June 1975 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Article

ArticleA Teacher with Chemistry

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Kathryn McKenna '91