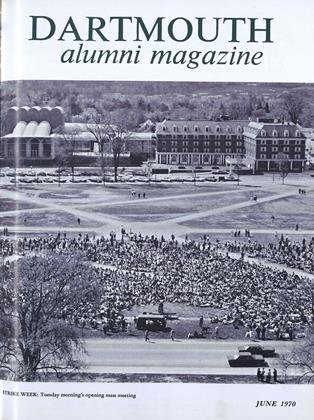

THE fabled Dartmouth community exists no more. Back in the horseand-buggy days, local farmers used to supply the College with produce and sons, the President used to swap pulpits with the preacher in Etna and the students used to go out into the countryside during the winter term to teach. Then the College approached a human and pastoral balance with the people of the Upper Valley of the Connecticut River. Today, while the College as a realtor, financial institution, and employer extends its hegemony over the region, Dartmouth stands not as a community but as a disunity. The division between the College and the staff members who serve it was demonstrated during the strike.

Before assessing the impact of the strike on the more than 2,000 permanent college workers, one must analyze their crucial role in running Dartmouth. The principal quality of the Dartmouth staff is invisibility; letters are typed, wastebaskets emptied, books searched, meals served, all services are rendered with a minimum of friction. Unfortunately, the hidden cost of these services is human hardship. There is no way to measure the high degree of loyalty which most Dartmouth workers feel towards their employer, but it is very easy to measure the economic dilemma which confronts them. Caught between the rising local cost of living which surpasses the national urban average and a regressive property tax structure which most severely penalizes the small farm and home owner, the Dartmouth staff have seen their real wages decline to 1967 and 1968 levels. The last annual wage increase for most Building and Grounds workers was less than that period's increase in the cost of food, which usually amounts to onethird of a worker's budget. In an economy move, the College has ceased to fill vacated positions since last fall, stepping up the work load for those who remain on the job. Simultaneously, an increase in number of administrative and supervisory personnel has multiplied the bureaucratic barriers for workers.

The Dartmouth worker with roots in the Upper Valley is on the cutting edge of the general economic decline of Northern New England. As the mills and factories shut down while small farmers sell out or go bankrupt, the worker has no alternative. He cannot afford to leave; neither can he afford to stay.

In allowing all staff members to participate in the week of discussion and reflection without loss of pay, President Kemeny went along with the proposals made Sunday night by the Strike Steering Committee, which assumed that during these extraordinary times Dartmouth staff members should have the same rights as students and faculty. On Tuesday, members of the Committee sought and got assurances from Kemeny that these rights included the right not to strike; specifically, a worker (like any student or professor) had the right to attend workshops, to go to work as usual, or to engage in any other activity. Striking students and faculty, in attempting to educate workers and guarantee their rights, were educated themselves about the problems of the invisible members of the community.

Some staff members took part in strike activities and some chose to take the time off. Students who pictured campus employees as gruff, stolid "Emmets" with Union-Leaders in their hip pockets were rather surprised by the number of workers at films, lectures, and discussions. Most of the workers who came didn't have much to say, like the elderly woman from Thayer Hall who had lost a son in Vietnam and wanted to know why.

Yet, the majority of the college staff chose not to participate. Secretaries remained loyal to their bosses, boilermen performed.their necessary jobs, janitors remained responsible to buildings they had served for years. Some of the staff who disagreed with the political tone and style of the strike ignored the whole proceedings, but others came to argue and debate in workshops. Many workers were motivated not to take part by fear — fear of violating the routine, fear of being put down by students, fear of what fellow workers or the boss might think, fear of possible reprisals in the future, despite President Kemeny's guarantees.

In one of the most successful operations of the strike, the Strike Committee set up a job replacement for staff members who wanted to take leave from work. Dormitories organized to collect trash, mop and vacuum, in order to liberate their janitors. The library established an extremely efficient substitution system. At Thayer Hall and the Hopkins Center snack bar, volunteers were turned away in droves after vacant positions were filled. For a brief time, students, faculty, and townspeople were exposed to a different perspective of the College. Some medical students and a local school teacher attempting to replace some second-shift employees found them overworked, extremely timid and unaware of their right to participate in the strike. Further investigation led to a call to President Kemeny who affirmed that the second-shift workers in fact were expected to remain on the job because there were no strike activities scheduled.

An important event of the strike was the workers' workshop Thursday afternoon. Organized by workers for workers to discuss the relationship between the staff and the community, the meeting was attended by over 120 employees from the library, Thayer Hall, Building and Grounds, and the offices about campus. Although several supervisors also showed up, workers were fairly candid in their remarks about the College's treatment of its staff. One janitor who had served Dartmouth for nearly twenty years spoke very movingly of his dilemma as a recently widowed father of three striving to maintain a home and a household on less than $75 a week. Despite apparent frictions between various segments of the college work force, the general consensus reached by the gathering was that Dartmouth employees must define their common grievances and organize in common to gain dignity and fair return for their labor.

The strike for the staff ended Monday morning, May 11, with the order by Director of Employee Relations Clarence Burrill returning all employees to normal working schedules. The next day President Kemeny confirmed this return to business as usual, despite the mass vote on the previous Friday, when over a thousand people called for a continuation of the strike for workers as well as students for the remainder of the term. Many staff members evaluated the whole affair as nothing more than the annual outbreak of spring juvenility. Perhaps they were right. Perhaps, however, this spring might engender an honest reappraisal of the vital function workers play at Dartmouth. For the first time, students, faculty and townspeople supported the rights of campus workers to join in the councils and events of the community.

Two images from the strike are called into mind. The first is of the Faculty meeting Friday night which helped decide the course of the strike. Three Blue Ladies from Thayer Hall, politely inquiring, were turned away from the meeting by the Dean of the College. The second image is of the green earlier that evening, as lengthening shadows crossed the baseball diamond. Playing Softball on the green, which Buildings and Grounds personnel rarely cross, were six B&G men. The first image is the unfortunate reality; the second, the plausible future.

Students manned a day nursery in theFaculty Lounge so parents could takepart in the activities of Strike Week.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFor Want of a Better Word They Called It a Strike

June 1970 By DAVID MASSELLI '70 and WINTHROP ROCKWELL '70 -

Feature

FeatureSix Professors Reach Retirement

June 1970 -

Feature

FeatureNew Environmental Studies Program To Be Launched in the Fall

June 1970 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1970 -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT KEMENY'S RADIO TALK

June 1970 -

Article

ArticleWhat the Workshops Meant

June 1970 By GUY DE MALLAC-SAUZIER