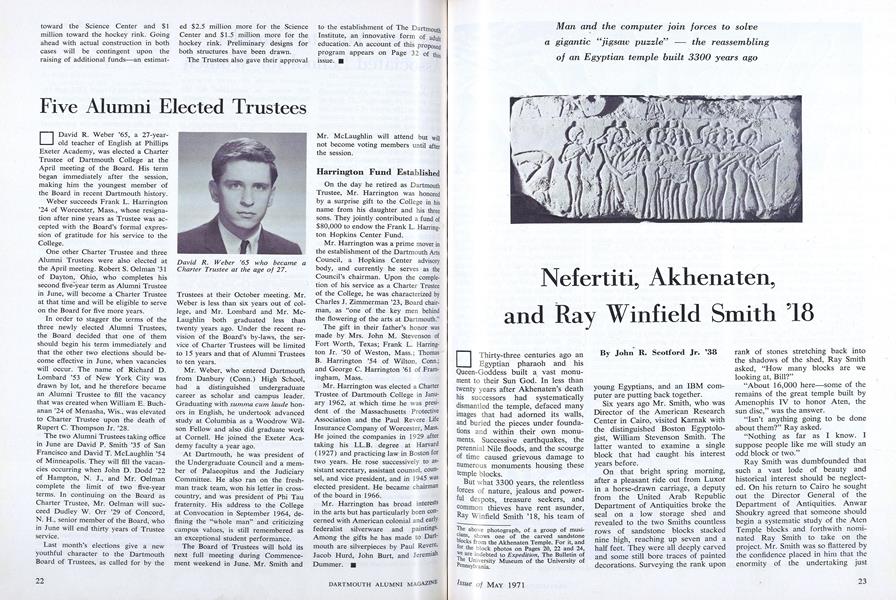

Man and the computer join forces to solvea gigantic "jigsaw puzzle" - the reassemblingof an Egyptian temple built 3300 years ago

Thirty-three centuries ago an Egyptian pharaoh and his Queen-Goddess built a vast monument to their Sun God. In less than twenty years after Akhenaten's death his successors had systematically dismantled the temple, defaced many images that had adorned its walls, and buried the pieces under foundations and within their own monuments. Successive earthquakes, the perennial Nile floods, and the scourge of time caused grievous damage to numerous monuments housing these temple blocks.

But what 3300 years, the relentless forces of nature, jealous and powerful despots, treasure seekers, and common thieves have rent asunder, Ray Winfield Smith '18, his team of young Egyptians, and an IBM computer are putting back together.

Six years ago Mr. Smith, who was Director of the American Research Center in Cairo, visited Karnak with the distinguished Boston Egyptologist, William Stevenson Smith. The latter wanted to examine a single block that had caught his interest years before.

On that bright spring morning, after a pleasant ride out from Luxor in a horse-drawn carriage, a deputy from the United Arab Republic Department of Antiquities broke the seal on a low storage shed and revealed to the two Smiths countless rows of sandstone blocks stacked nine high, reaching up seven and a half feet. They were all deeply carved and some still bore traces of painted decorations. Surveying the rank upon rank of stones stretching back into the shadows of the shed, Ray Smith asked, "How many blocks are we looking at, Bill?"

"About 16,000 here—some of the remains of the great temple built by Amenophis IV to honor Aten, the sun disc," was the answer.

"Isn't anything going to be done about them?" Ray asked.

"Nothing as far as I know. I suppose people like me will study an odd block or two."

Ray Smith was dumbfounded that such a vast lode of beauty and historical interest should be neglected. On his return to Cairo he sought out the Director General of the Department of Antiquities. Anwar Shoukry agreed that someone should begin a systematic study of the Aten Temple blocks and forthwith nominated Ray Smith to take on the project. Mr. Smith was so flattered by the confidence placed in him that the enormity of the undertaking just served to whet his well-demonstrated appetite for a tough problem. He knew that the task of reassembling, even on paper, more than 35,000 blocks of stone was a jigsaw puzzle of gigantic proportions, something bigger and more difficult than any archaeologist had ever attempted before.

One special problem was that all of the blocks were of just two types. Each block is about two feet long, ten inches high, and ten inches deep. They are carved and painted on either the long side and laid up as "stretchers," or on the end and laid up as "headers." The walls of the temple were made up of alternating rows of stretchers and headers.

A second big problem was that the blocks were not all in one place. In addition to the several storehouses full at Karnak, thousands were piled up in the open at Luxor. Aten Temple blocks were still being pulled from the interior of the later Ninth Pylon at Karnak, one of ten such ceremonial gateways making Karnak one of the most imposing ruins in the world. And numerous other individual blocks had been smuggled out of Egypt by pilferers and lay in museums in many countries.

Obviously the customary techniques of reassembly would take too many people too many years and cost too much. An actual reconstruction was out of the question. Early estimates indicated that the temple might have stretched over a mile into the desert, and its location is uncertain. No, the temple would have to be reconstructed on paper. While this would not result in an imposing monument like the Temple at Luxor, it would, however, be just as meaningful, perhaps more so, to scholars all over the world, and would inspire large segments of the general public.

The blocks piled up at Karnak and Luxor and those being freed from their hiding places in the Ninth Pylon could be photographed and described one by one. Data on the blocks in museums elsewhere could be gathered. But the result would still be a great hash of unrelated facts. Some way must be found to bring it all together. For it was only as a unity that the Aten Temple would begin to make sense and reveal the thinking and artistry of those who built and decorated it.

Ray Smith turned to the electronic age for help. He knew a vast amount of data could be recorded and, more importantly, digested, compared, and retrieved at superhuman speeds by modern computers. His reputation as a scholar who has added so much to man's knowledge of ancient glass and his connections in the worlds of business and diplomacy made him uniquely able to enlist the cooperation of a great team of institutions and people.

With the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania as institutional sponsor (he was appointed a Fellow), the present expedition has the financial support of the Foreign Currency Program of the Smithsonian Institution. The National Geographic Society has provided further funds and invaluable photographic counsel, and has published one Ray Smith article about the project in the November 1970 issue of National Geographic. The International Business Machines Corporation gave freely of their expertise in helping Mr. Smith reorganize the data for reassemblies, using their computer procedures.

James Delmege of Rome was put in charge of photographing the blocks. Each one was photographed with the lens of the camera exactly opposite the block face so there would be no distortion of the image, and from exactly the same distance so all blocks would be to the same scale. Black and white film was used but the colors of the painted decoration were carefully recorded with other identifying information as each block was photographed. A nine-digit number was placed on each block so that it appeared in the photograph and would never be separated. As Delmege and his crew perfected their procedure they could shoot as many as 400 blocks a day. When the photographs were developed and printed, Ray Smith's Cairo staff went into high gear. This group of young graduates in Egyptology from the University of Cairo transcribed the data recorded for each block as it was photographed and added to the coding sheets all the significant visual details to be seen in the photograph. The IBM Computer Center in Cairo transferred this information to punch cards and then to magnetic tape.

Few details about the builders of the Aten Temple are known to historians. Akhenaten ruled, from 1367 to 1350 B.C., a world empire that embraced Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and the Sudan. Prior to his reign Egyptians like most of the rest of the world worshiped many gods. But Akhenaten developed an interest in one god, Aten, a deity represented by the sun disc. As his faith in monotheism and his belief in Aten crystallized he changed his name from Amenophis, meaning "Amun is satisfied," to Akhenaten or "beneficial to Aten." The historian James Breasted has identified him as "the world's first idealist ... the earliest monotheist, and the first prophet o f internationalism—the most remarkable figure of the Ancient World before the Hebrews." That he was an idealist in more than just philosophy is proven by his choice of a bride. He chose as his Queen a girl whose beauty has become legend, Nefertiti, whose name is translated as "The Beautiful One Is Come." Even today the famous sculptured head of Nefertiti in the Egyptian Museum in West Berlin radiates an aura that erases the centuries and fascinates the viewer with her loveliness and queenly bearing.

Ray Smith now traveled to Europe and America to examine and photograph the Aten Temple blocks that had been spirited out of their homeland to enhance the world's great museums and private collections. In some cases the blocks had disappeared but photographs had usually been taken and pertinent data catalogued.

Meanwhile back at project headquarters in Cairo information on enough of the 35,000 blocks had been computerized to see if the space-age system for matching up the jigsaw puzzle would work. Data on the fugitive stones and those still in Egypt were fed to the computer. To facilitate the matching, 19 categories of scenes were given specialized computer "lists": figures; sunrays; hieroglyphs; animals; architectural details; defacements, and so forth. These lists were then subdivided— the figure list, for example, into kings, queens, princesses, priests, courtiers, and slaves.

Mrs. Asmahan Shoucri and Dr. Sayed Tawfik of the Cairo staff started with the photograph of a header block on which was carved Akhenaten's right elbow. The computer was asked to help find the stretcher block next above. Some 218 blocks were listed by the computer as showing parts of the King in the proper scale. The choice was successively narrowed down by the additional criteria of: profile facing right; cut off at shoulder height; rays of the sun parallel to upper arm; until just one choice remained. That print was brought from the file and it matched! Going on to the header with the rest of his crown, and to the other blocks around the figure, was easy as staff workers asked the right questions about remaining paint flecks, size of details, angles of the sunrays, and logical matching hieroglyphs. One of the first match-ups completed the inscription "The god's heart is pleased." An auspicious beginning.

The work in Cairo is still going on. Ray Smith flew back to Egypt last October to rejoin the forces in the field and to devote eight more months to concentrated work on his thriller chase. Now that they know the computer technique will work, much scholarly attention is being given also to the newly revealed details of the lives of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and to the new understanding of this period of history.

It is known that as the Aten Temple was being built the pharaoh changed his name to honor his The characters spelling out his original name Amenophis were scratched out in the earliest parts of the temple and the name Akhenaten was substituted. In later parts it is clear that the characters spelling Akhenaten are the original carving. The emergence of Nefertiti as a Queen-Goddess is reflected in the vast pillared courtyard that celebrates "The Beautiful One" and her daughters. The decorations in this courtyard and its dozens of square columns are dedicated exclusively to Nefertiti and the princesses. Nothing masculine appears— no mention of Akhenaten, no male slaves or courtiers, not even male animals are depicted. A unique tribute to femininity, an honor rendered to no other Egyptian queen.

Apparently the area of Thebes was too closely associated by Akhenaten with the rejected god Amun, God of the Empire. As the Aten Temple was nearing completion, Akhenaten moved his court to Tell el Amarna, 240 miles down the Nile, and there on an uninhabited site built a new capital. The Amun priests were surely offended by his treatment of their god and probably felt that his preoccupation with an opposing religion was bringing about a neglect of the affairs of state. Rebellion in Western Asia was growing and by the time of his death, only seventeen years after he had succeeded his father, Amenophis III, the Egyptian empire was collapsing.

He was succeeded by Smenkhare, who reigned briefly, and then by the husband of one of his and Nefertiti's daughters—Tutankhamun (King Tut of the Sunday supplements of the early twenties). The Egyptian court reverted to unbridled polytheism and returned to Thebes. The pharaoh Ay followed Tutankhamun and was followed swiftly by the commonersoldier Horembeb. He built the mighty Second Pylon of Karnak and used the blocks of Aten in it. He was careful never to use the blocks where their decorations could be seen. They were inserted like dominoes in a box inside the Second Pylon. Slices of the Nefertiti pillars were brought from the temple, stone by stone, to the Second Pylon, where they were carefully reassembled in their original juxtapositions. This is most puzzling, because they would remain hidden from human eyes forever. The explanation is to be found in the obviously contemptuous treatment of Nefertiti. Segments of pillars were placed under the massive exterior pylon walls, symbolically crushing the Queen by the enormous weight of the walls. Other segments were turned deliberately upside down, undignified treatment of a beautiful woman. Faces and bodies of Nefertiti were viciously defaced. Obviously Horembeb was sensitive about his own earlier relation to Akhenaten, and was determined to convince his nation that their new pharaoh was uncompromisingly opposed to the old order. Probably, also, he harbored a particular contempt for Nefertiti herself.

Throughout history many tyrants have tried to erase the records of their predecessors. And while such vandalism is always to be deplored, perhaps in this case we are the gainers. If the Aten Temple had remained standing, time and weather would have loosened its painted decorations, the wind-blown sands would have eroded the carvings. Earthquakes and the Nile would have added to the destruction. Also, the unused temple, over thirty-three centuries, would have been steadily plundered. Perhaps by trying to bury evidence of the reign of Akhenaten and Nefertiti the pharaoh Horembeb preserved it for Ray Smith, his team of Egyptologists, and their computer to rebuild on paper for us all.

That "rebuilding" job is moving steadily ahead, according to the latest word from Ray Smith in Cairo. From the massive photo file of more than 35,000 decorated blocks, thousands of blocks have already been matched and in some cases as many as forty stones have been put together in a photo mosaic that enables the staff to visualize the whole scene with great accuracy. It is Mr. Smith's expectation that some of these scenes will be physically reassembled, to take their place with the greatest treasures from ancient Egypt. But anything near a full-scale recreation of the Aten Temple, which had an estimated two miles of sculptured scenes, will have to be done on paper. There are tentative plans to publish the results of the project in one or more volumes, with color plates, and this in itself will be one of man's finest archaeological achievements—a monument to the fascinating reign of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, to the superhuman speed of the computer, and to the scholarly direction and unflagging enthusiasm and effort of Ray Winfield Smith. The above photograph, of a group of musician, shows one of the carved sandstone blocks from the Akhenaten Temple. For it, and for the block photos on Pages 20, 22 and 24, we are indebted to Expedition, The Bulletin of the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania.

This deeply chiseled block depicts cattle being slaughtered for sacrifice to the god.

One of the scenes from nature, a female jackal runs with her mate, partly shown at lower right.

The famous sculptured head of Nefertitiin the Egyptian Museum, West Berlin.

In this temple block, Akhenaten is shown offering a figure of Maat, goddess oftruth, to the Sun-disc, central symbol of his monotheistic religion.

Artist Leslie Greener, with, carefully researched details provided by Ray Smith, has recreated the courtyard honoring Nefertitiwho is shown inspecting her monument as it neared completion The outer faces of the colored pillars repeat the sceneof Nefertiti facing herself across an offering table. The other sides show the queen-goddess being blessed by Aten's rays, each terminating in a hand. Establishing the existence of the courtyard, decorated exclusively with female figures, is one ofMajor discoveries of the Akhenaten Temple Project.

This block, especially wellpreserved in its details, waspart of one of the manyscenes of offerings beingmade to the Sun-disc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Institute

May 1971 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Vote to Consider Associated School for Women

May 1971 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1971 By JOEL ZYLBERBERG '72 -

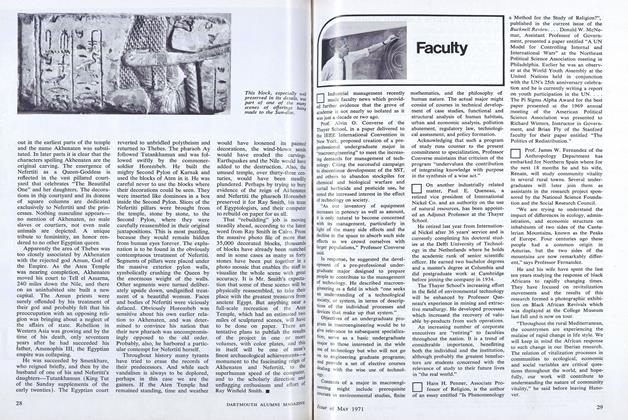

Article

ArticleFaculty

May 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleHanover's Famous May "Murder"

May 1971 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

May 1971 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, GEORGE PRICE

John R. Scotford Jr. '38

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

JUNE 1959 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

November 1976 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

JUNE • 1986 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

FEBRUARY 1991 -

Books

BooksSHOW ME THE WAY TO GO HOME.

January 1960 By JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. '38 -

Feature

FeatureThe Green Curve of the Future

JANUARY 1969 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38

Features

-

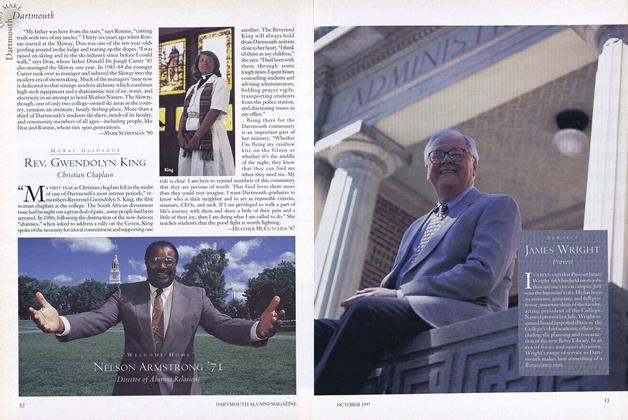

Cover Story

Cover StoryJames Wright

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

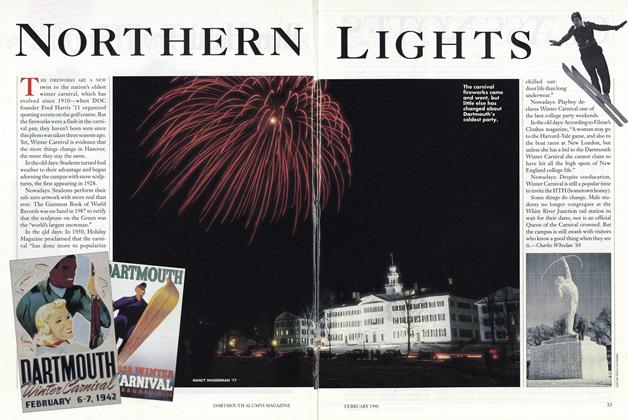

FeatureNorthern Lights

FEBRUARY 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

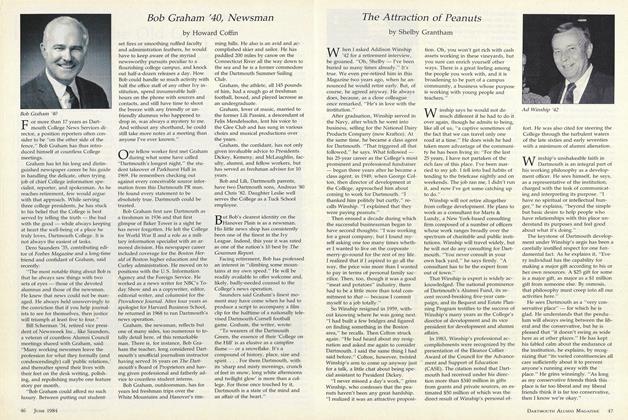

FeatureBob Graham '40, Newsman

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Howard Coffin -

Feature

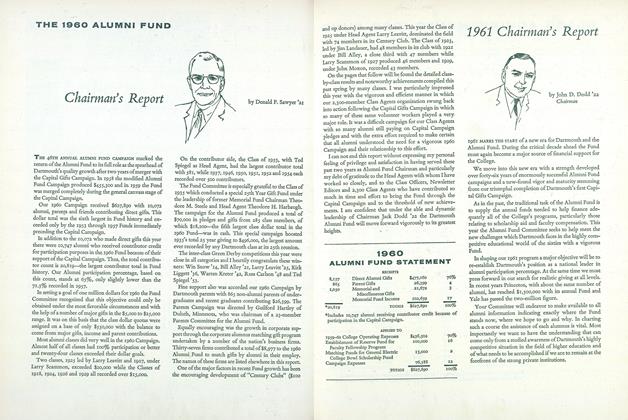

Feature1961 Chairman's Report

December 1960 By John D. Dodd '22 -

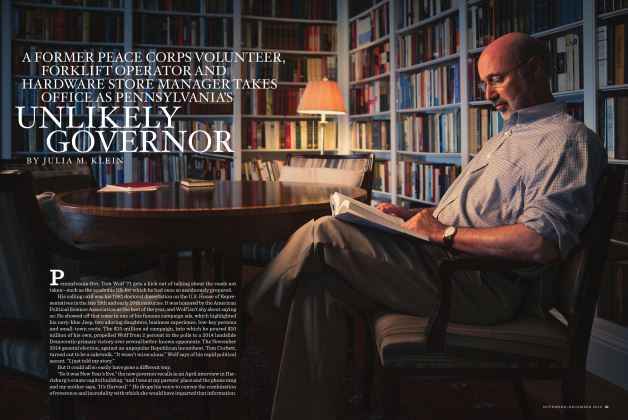

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Unlikely Governor

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

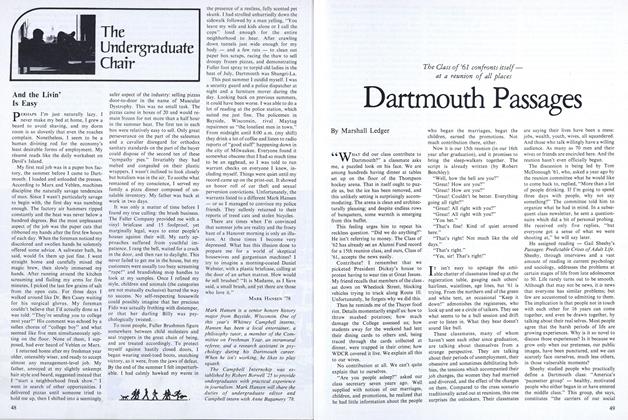

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Passages

SEPT. 1977 By Marshall Ledger