Mexican diplomat and novelist Carlos Fuentes was a Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth from January through July of 1981. Brian Phillips was a junior that year, and his comments were part of the three-page letter he wrote to the Montgomery Endowment Committee to express his "immense gratitude for the opportunity to have worked with this wonderful man, as his student and as his friend."

Kenneth Montgomery '25 and his wife Harle, the donors of the endowment, say they receive frequent expressions of thanks not only from students and faculty, but also from the famous people they have made it possible to bring to Hanover. "Each one we have talked with has expressed surprise at just how stimulating an experience it has been to be at Dartmouth," says Harle Montgomery. "All of them arrive not exactly sure what is expected and they all come away with the exuberant feeling of having achieved something and been exposed to wonderful students and an exciting faculty."

"We had originally hoped no further than providing the students with a great opportunity," says Kenneth Montgomery. "That, we are delighted to see, has happened. The program is unique and the students like it. What we hadn't foreseen was the way it would stimulate the intellectual life of the faculty and the community as well."

The Montgomery Endowment was conceived in the mid-seventies, and those involved all recount a favorite tale about its origins: A worried president was conferring with his librarian before a dinner party in New York with Kenneth and Harle Montgomery. John Kemeny explained to Edward Lathem that he had done some studying, the upshot of which had been an awkward realization: what the Montgomerys wanted to do couldn't be done for the one million dollars they were offering the College. The president was not looking forward to explaining to the Montgomerys that they would have to cut back the scale of the project or raise the ante.

The Montgomerys arrived. Pleasantries were exchanged. Drinks were ordered. "Before we get onto anything else/ said Kenneth Montgomery, "I want to tell you that Harle and I have concluded that what we've been talking about can't be done for a million dollars. So we've decided to give you two."

A few months later the details were hammered out, and Dartmouth's Trustees approved the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Endowment, a gift enabling the College to bring to campus some of the world's most distinguished people. It was, as a happy president explained to the press, an endowment as imaginative as it was magnificent.

The Montgomerys did not offer the College $2 million in cash. Instead, the gift came in the form of a donation of royalty interests in several Texas oil fields, thus making it one of the most unusual as well as most munificent gifts Dartmouth has ever received. The operating expenses of the Montgomery Fellows program are paid from a portion of this royalty income, with the balance set aside to establish an endowment that increases in size each year. The plan, explains Paul Paganucci '53, the College's vice president for finance, is designed so there will be sufficient assets on hand to support the program in perpetuity after the useful life of the wells. The royalties were valued at $2 million at the time of the gift, but oil interests have been good things to own lately, and Paganucci estimates that by the time the wells peter out probably in the late eighties the College will have benefitted to the tune not of two, but of five million dollars. Last year, the Montgomery program cost about $210,000, and at the end of fiscal 1983, the endowment assets (excluding roy- alties) were up to $2.7 million. (Four million dollars' worth of endowment is required to support $200,000 of annual expenditure, according to Paganucci.)

Kenneth Montgomery went to Harvard Law School after he graduated from Dartmouth and in time became a highly successful corporation attorney in Chicago. He was 60 when he inherited part of the Post cereal fortune, and since that time he has been a generous patron to several of the country's institutions of higher education. Dartmouth had already received a number of gifts from him before the endowment was created, explains Lathem, a personal friend of both Montgomerys, a prime mover in the complex crafting of the endowment, and currently its executive director. Lathem mentions a sociology-of-the- family laboratory, $10,000 gifts to the library ("mad money for the librarian," he recalls with a smile), commissioned portraits, various publications, and a handsomely-appointed computer terminal room for the library.

But, continues Lathem, the time came when the Montgomerys decided they wanted to do something to make a major impact at Dartmouth. As a result of a good deal of brainstorming among the Montgomerys, Kemeny, Lathem, and the College's provost, Leonard Rieser, a plan evolved for a program that would enhance the undergraduate experience at Dartmouth by bringing to the campus distinguished artists, academics, and public figures "creative and innovative thinkers without restriction as to field or endeavor" who would be in residence long enough to make a significant educational contribution and to permit students to get to know them "The idea was," explains Kenneth Montgomery, "that nothing would be demanded of the Fellows except that they like students and not be recluses.

We wanted to encourage an intermingling of students and Fellows, who would spend time together discussing the problems of life."

The Montgomerys were firm about wanting the visitors to be people who enjoyed working with students outside as well as inside the classroom and who would make themselves easily accessible to undergraduates. Kemeny felt strongly that such a program would require a residence. The hardest thing about attracting distinguished people to a campus for any length of time, he explained, is not having a suitable place to house them and their families. The president's arguments were convincing, and the Montgomerys turned their considerable joint energies toward the acquisition of a suitable house, one close enough to campus to facilitate easy interchange with students and elegant enough to tempt the luminaries of the world.

Leonard Rieser, who served for five years as chair of the Montgomery Endowment steering committee, recalls the ups and downs of the long search: "It's important to realize that the Montgomerys are not people who drop their money and run. When they understood that a house was desirable, a house became an overriding concentration for them. We and they looked for over a year; we even considered building. Then Adelbert Ames' widow, Fanny Ames, died, and their home on Rope Ferry Road came on the market. It was an extremely wellbuilt house with landscaped gardens backing onto Occom Pond a unique property." Dartmouth secured the house, according to Rieser, "by the skin of its teeth." At one point in the negotiations, apparently, the Ames family became uncertain about wanting to sell the house at all, and it was the Montgomerys' willingness to hang the cost that made the difference.

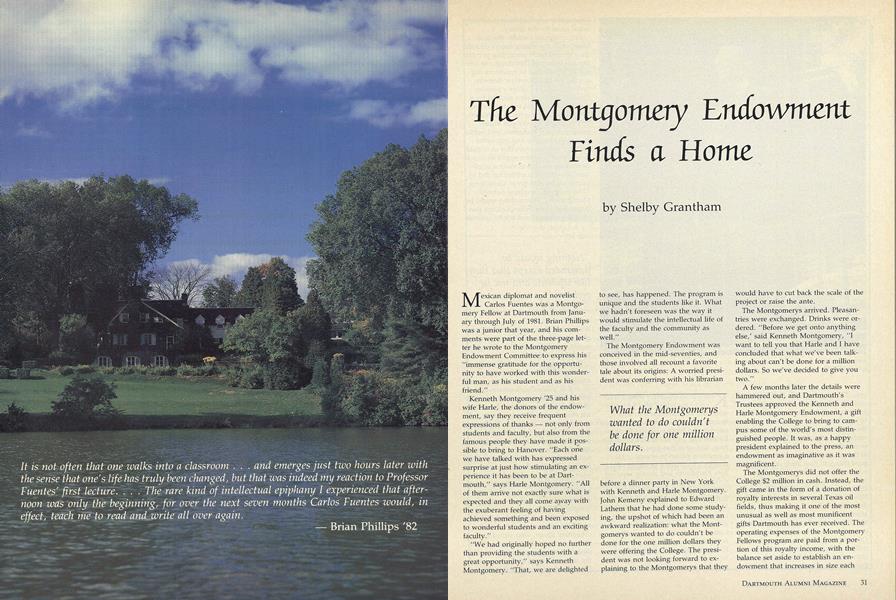

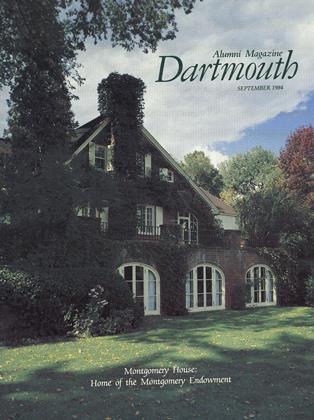

Montgomery House is an elegant brick-and-clapboard residence whose large rear windows overlook a series of terraced gardens leading down to Occom Pond. The gardens, walled in red brick and recently restored to some of their original glory, change from cultivated beds near the house to birch-studded meadowlands rich in wildflowers at the edge of the pond.

Very little renovation was necessary, says Lathem, except to do. away with the butler's pantry in order to enlarge the kitchen. The six-bedroom house was, however, completely redecorated and refurnished, at a cost of some $70,000; and when it was later discovered that the asphalt roof needed replacing, the decision that the house deserved a slate roof was unhesitating, despite the expense.

There are two studies in the house, one of which is becoming something of a Fellows Library, since it houses the collection of printed works inscribed by the residents in a thank-you gesture that has become a tradition at Montgomery House. Some inscriptions are perfunctory "Toni Morrison, Montgomery Fellow 5.26.1982," reads the flyleaf of a copy of Morrison's novel Tar Baby, for instance and others are more personal, such as the one inside a copy of The Sirens of Titan by Kurt Vonnegut, who signs himself "a pampered and contented guest in Montgomery House, April 26-May 1, 1983."

A modernized kitchen, a handsome dining room with a fireplace, and a pleasant sunporch off the formal living room make the house versatile and comfortable. The wallpapers chosen by the Montgomerys' decorator are wonderful, from the plain dark gray used with white trim in the master bedroom to the delicate blue-on-white colonial design in the kitchen and the big, bold modernist radishes on a white ground in the back bath. The furnishings, some modern, some antique, include many beautiful leather-bound editions a red Dickens, a blue Voltaire, a rust-colored Poe though a comfortable selection of less august volumes has also been included. The Story of jimmy Durante sits cheek-by-jowl with the leather-bound Dante, for instance, and the shelves of the Fellows Library are filled out with such intriguing titles as Farewell to Foggy Bottom, People's Wants and How to Satisfy Them, and Ask Me Anything.

The house was furnished "minimally" in the beginning, explains Harle Montgomery, because of a lack of time before the scheduled arrival of the first Fellows sociologist Elise Boulding and her husband, economist Kenneth Boulding. "We hope," says Mrs. Montgomery, "to add to the furnishings bit by bit, as suitable antiques turn up." Already several friends, as . well as other members of the Montgomery family, have made gifts of furnishings and art works for Montgomery House. Another long-term project initiated by Mrs. Montgomery is the acquisition for the house of student works of art a project that has delighted everyone connected with the endowment.

Perhaps the most impressive place in the house is the basement-level room known as the Pine Room. It is a grand, pine-paneled hall with a baronial fireplace and arched windows overlooking the pond. The Pine Room is used now for classes and films hosted by Fellows, and a small kitchen has been installed off of it to make entertaining students there easy.

Montgomery Fellows stay at Dartmouth for varying periods of time, from a few days to as much as a calendar year, explains Barbara Klunder, assistant to the provost, who manages the house and schedules its occupants. She tries to dovetail visitors' particular interests with events on campus in an effort to promote as much interaction between Fellow and College as possible. She contacts departments that might be interested in having some of a Fellow's time and sets up appointments with members of the College community who express an interest in meeting with a given Fellow. Klunder schedules her shortterm visitors relentlessly, to give them the greatest exposure possible, but her ideal Fellow is one who comes for a whole term and teaches a class. "Then things are more relaxed, the Fellow is more like a regular faculty member, and all sorts of requests can be accommodated." One of the hardest parts of her job, she says, is figuring out the energy levels of her charges "Edward Heath wanted even more interaction with students than I had scheduled him for, and he got the students to take him on a 'pub crawl,' whereas someone else complained that I left him no time to jog in the mornings." The other thing that gives her headaches is trying to guess the size of the draw for the public lectures Fellows often give, so that she can book the proper auditorium on campus. "It's psychologically important to fill the auditorium but, of course, not to overfill it," she says. "Sometimes you guess wrong."

Rieser found his most difficult task the securing of acceptances from the famous people invited to become Fellows. Leonard Bernstein, he says, has been the biggest challenge so far, because of conflicting schedules, and, in fact, College and composer have put their ill-starred attempts to get together on hold for the moment. Rieser found British immunologist Peter Medawar, invited as part of a Montgomery Endowment series on issues in the natural sciences, the easiest to engage. He recalls deciding one evening, after a long spell of pondering approaches, simply to telephone and ask. "A woman answered and I said, 'Mrs. Medawar?' She replied that she was, indeed, Lady Medawar. I explained that I was calling for a strange reason that we would like for her husband and her to come to Dartmouth for a week. 'We're expensive,' she said, 'because my husband is in poor health and we have to travel first class.' I said that was fine. 'Would you please explain the invitation to my husband directly?' she asked. I did.

He listened and then said, 'Fine. We'll be there on the ninth.'"

One amusing story Rieser tells involved two statesmen invited as part of the same series on the American presidency that also brought former President Gerald Ford to Dartmouth. "Both former British Prime Minister Edward Heath and former Under Secretary of State George Ball had telephone calls from Henry Kissinger while they were here," recalls Rieser with a grin. "Kissinger seemed somewhat surprised that the people he was trying to reach were always at this odd number in New Hampshire. He must have wondered, too, why he wasn't here."

Although the first year of the program was, as one would expect, tough going, the ever-lengthening list of notables has become very impressive. Montgomery Fellows are company people like to keep. Rieser cannot think of any distinguished visitor program just like Dartmouth's, nor can the Montgomerys. "What is unique," says Rieser, "is the combination of a fellows program and a house devoted solely to the program. Kemeny's hunch was right. It's wonderful leverage to be able to say to a prospect, 'You will stay in an elegant house.' I remember how delighted Lady Medawar was when I told her that. 'Oh, wonderful!' she said. 'We like elegant houses.' "

The endowment receives national coverage from time to time these days, the latest occasion being a New Yorker interview by Philip Hamburger with Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Barbara Tuchman, who was at Montgomery House in February of this year. "We are just back from a wetek at Dartmouth," she is quoted as saying. "I was a Montgomery Fellow. One gets the royal treatment! A limousine to drive us from Cos Cob to Hanover, a house all to ourselves, appearances everywhere. I hate to lecture to rows of students with glazed eyes, but this was a whirlwind of seminars and group meetings, ranging from modern American to British history, and even getting into The Iliad and Plato. A mixed bag. Oh, and I met with humanities students, and touched on military history in the Second World War. I enjoyed myself, and I loved the perks."

Everyone is pleased about the Montgomery Endowment including the Montgomery's. "The association with the College, with Fellows, with the faculty and the students has been wonderful for us," they declare. "We have personally gained more than anyone else out of the fun we have had with this program."

It is not often that one walks into a classroom... and emerges just two hours later with the sense that one's life has truly been changed, but that was indeed my reaction to Professor Fuentes' first lecture.... The rare kind of intellectual epiphany I experienced that afternoon was only the beginning, for over the next seven months Carlos Fuentes would, in effect, teach me to read and write all over again.

Sherman Adams, former U.S. chief of staff, was a Fellow at Montgomery House in the spring of 1980.

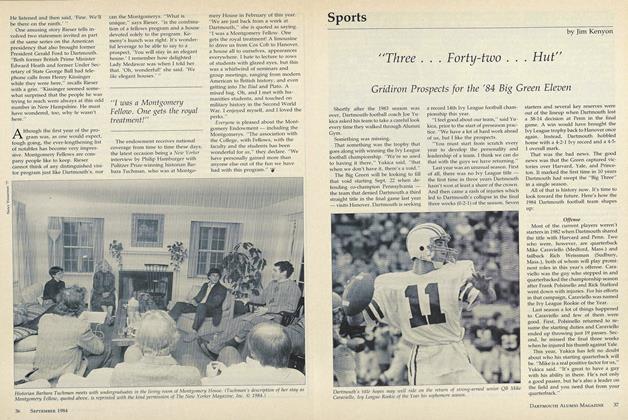

Historian Barbara Tuchman meets with undergraduates in the living room of Montgomery House. (Tuchman's description of her stay as Montgomery Fellow, quoted above, is reprinted with the kind permission of The New Yorker Magazine, Inc. 1984.)

What the Montgomerys wanted to do couldn't be done for one million dollars.

"Nothing would be demanded except that they like students and not be recluses

"Edward Heath got the students to take him on a pub crawl.' "

"I was a Montgomery Fellow. One gets the royal treatment!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

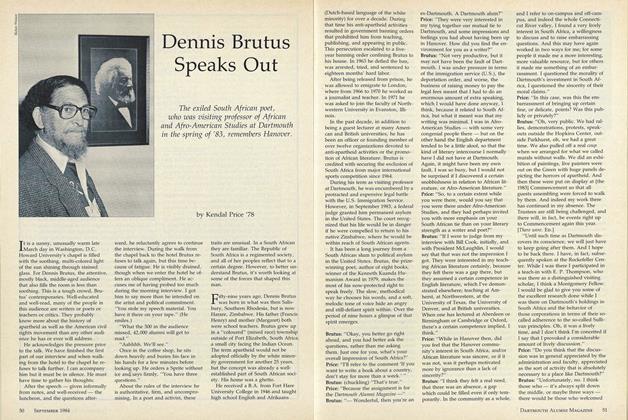

FeatureDennis Brutus Speaks Out

September 1984 By Kendal Price '78 -

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

September 1984 By Jay Parini -

Feature

Feature"Three ... Forty-two ... Hut"

September 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Innocent Ardor and Delight": A Tribute to Richard Eberhart

September 1984 By James Melville Cox -

Article

ArticleRumblings On Fraternity Row

September 1984 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Article

ArticleBob Blackman: Tackling Retirement in Hilton Head

September 1984 By Mary Ross

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

NOVEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

DECEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth at the Movies!

November 1982 -

Feature

FeatureDOCTORS, ESKIMOS and DOGS

November 1954 By DR. ERWIN C. MILLER '20 -

Feature

FeatureA Fulbright Year in France

November 1960 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2005 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureMAIN STREET

JUNE 1982 By Nancy Wasserman -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Nov/Dec 2008 By TIM FITZGERALD