"Education for Moral Responsibility

THE William Jewett Tucker Foundation, created by the Dartmouth Trustees "to support and further the moral and spiritual work and influence of the College," was formally inaugurated last month with an academic convocation during which Prof. Fred Berthold Jr. '45 was installed as the first Dean of the Foundation.

In addition to the installation ceremony which opened the four-day program, having the theme "Education for Moral Responsibility," four addresses were given by prominent men and three discussion meetings were held. The speakers and their subjects.were Dr. Philip E. Jacob, Professor of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania, "Changing Values in College"; Dr. Gordon W. Allport, Professor of Psychology at Harvard, Discrimination on the Campus"; Charles P. Taft, vice president of the National Council of Churches of Christ and former mayor of Cincinnati, "Self-Advancement"; and Lewis Mumford, author and philosopher, "The Moral Challenge Facing Democracy."

One of the three discussion groups was jointly led by Dr. Edward D. Eddy, Provost of the University of New Hampshire, and Dr. Kenneth Underwood, Professor of Government at Wesleyan University, whose topic was "Should the Classroom Instructor be Concerned with 'Education for Moral Responsibility'?" Another dealt with "Discrimination on the Campus and was led by Professor Allport. The third discussion, on "Student Self-Education, was led by Miss Sheila Slawsby of Wellesley, J. Robert Hillier of Princeton, and Kurt Wehbring '59 of Dartmouth.

At the installation ceremony in Rollins Chapel opening the convocation on Thursday evening, November 13, the sermon was preached by the Rev. Henry Pitney Van Dusen, president of Union Theological Seminary. The other speaker was Dean Berthold, whose response appears in full on the next page.

Rollins Chapel was the scene also of the convocation's concluding event Sunday morning, when a College Worship Service was held, with the Rev. David A. MacLennan, minister of The Brick Presbyterian Church, Rochester, N. Y., as guest preacher.

The convocation produced a variety of approaches to the general theme of "Education for Moral Responsibility." In the following excerpts from Dr. Van Dusen's sermon and the four main addresses of the convocation, we present some of the ideas heard by the Tucker Foundation audiences of students, faculty, alumni and guests of the College.

Dr. Van Dusen

THIS service marks the meeting point of two of the most powerful and persistent concerns of the human spirit: the enterprise of education, dedicated to the quest for truth, in the confident assurance that it is truth which sets men free; and the heritage of religion, declaring its guardianship not of all truth to be sure, but of the ground and principle of truth.

"However these two great interests of the human spirit - education and religion - may differ, however far apart their paths may at times appear to diverge, they profess a common allegiance to a single sovereign, truth. It is obvious that, if each rightly apprehends that sovereign and his command upon them, they should find themselves yokemates, fellow warriors in a common battle against ignorance and error. The relations between religion and education, therefore, must always be primarily a matter of truth - the liege-lord to whom both profess an absolute allegiance. By the same token, if there be strain or misunderstanding between education and religion, it must be basically because of divergent conceptions of truth, whether that divergence be overt or hidden.

"No one will question, I think, that we stand today just beyond another point of decisive transition. We have already moved far into a day when religion has again become a major concern of the American people. Yes, and of the American undergraduate. It is a day which opens the possibility of achieving something of a synthesis of the valid truths of both the initial thesis and the recent antithesis - the sound principles which guided the launching of American education and the vast achievements of the immediate past. Indeed, I think we may say that the two most obvious - and most important - features of the present position with respect to our topic are just these: (1) increased concern for the role of religion in education, and (2) deepening confusion and uncertainty as to the rightful relation of religion and education.

"To the most basic query of all: 'Why should education find a place for religion within its total program?' a partial answer may be discovered in at least four considerations:

"1. The first is the recognition that religion has been, and is, one of the most widely prevalent, pervasive and powerful forces in the life of humanity — in all ages, among all peoples, at all stages of cultural advance. To be unaware of that fact — and of its most characteristic expression, in common worship — is to be without one of the essentials for intelligent human living.

"2. Second, and more particularly, in the society of which we are immediate heirs - Western civilization in general - the Judaeo-Christian religion has been probably the most single formative influence.

"3. Third, religion has to do with the most elemental, the most universal, and, in the end of the day, the most important issues of human existence - its origin, its nature, its meaning and purpose, its destiny; especially with the inescapable and determinative events which mark and mould each person's life - birth, love, parenthood, death.

"4. Lastly, there is the more theoretical but even more basic issue, to which I referred at the outset, of the nature and ground of truth - the elemental recognition that if there be a God at all, He must toe "the ultimate and determinative Reality, through which all else derives its being; and the truth concerning Him, as best man can apprehend it, must furnish the keystone to the ever incomplete arch of human knowledge."

Professor Jacob

DARTMOUTH'S attempt to reunite liberal learning and moral purposefulness in a way which has relevance for college students in the second half of the twentieth century is an audacious undertaking, considering the environment of student values with which it must come to terms.

"I expect that President Tucker, in the appeal which now expresses the aim of this new venture, spoke to a responsive body of students and to an American college community which broadly shared his concern and underlying assumptions. Today, the prevailing pattern of student values appears markedly inhospitable to the linking up of higher education with moral responsibility. A dominant characteristic of American college students in the 1950's - always allowing for a minority who differ - is their moral irresponsibility. Of equal significance is the way their moral control tower - the mechanism by which they reach value judgments - is sealed off from the influx of intellectual communications. A hiatus seems to have split the educational process from the real life of many students, the world of knowledge and reason from the world of vital personal choices, the student's learning from the values he holds.

"These two features of the contemporary pattern of campus values - moral irresponsibility and the imperviousness of student values to the tutelage of the mind - obviously challenge the very heart of the concept to which the Tucker Foundation is dedicated. The question which must haunt President Dickey, Dean Berthold and their student and faculty associates is whether they are caught in an irreversible sweep of student disposition, or whether these circumstances can be changed by the right kind of educational leadership. * * *

"The pivot of the value system which pervades the campus is an absorbing selfinterest. Students appear overwhelmingly dedicated to the pursuit of happiness - for themselves. They intend that what they do in life shall contribute directly to their personal enjoyment. They do not expect to derive much satisfaction from activities which are concerned with the needs of others, in their communities, their nation or the world at large. Nor do they plan to waste much of their time or substance on such activities. Each choice - of job, of associates, or residence, of personal conduct, even of mate and size of family - is governed by one well-calculated and candidly admitted criterion 'What will it do for me?' * * *

"This preoccupation of students with themselves does not make them antisocial. They intend no injury to others in the pursuit of their own enjoyment. These are not the grasping acquisitors of America's Iron Age. They do not expect to gain their personal satisfactions through squeezing others out of theirs. But why care about someone else? What he wants and does should be his business. Each for himself, but the devil need not take the hindmost because there is enough of the good life for any who want it enough to seek it out. At least there is enough to go around among the college-educated.

"Far from making them anti-social, the students' pursuit of self-satisfaction in tire American environment draws them into an extraordinary dependence upon the social groups with which they are identified or with which they hope to be identified in the future. They take for granted that they will have to realize their personal aspirations in conjunction with others - even if they are not really concerned for the welfare of others. The price they must pay for the enjoyment they wish for themselves is to get along well with other self-seekers in our highly organized, grouporiented society. * * *

"The picture is of course a composite, a portrayal of features characteristic of the mass. It does not accurately describe any particular student. Nor does it apply even in a general way to all students. Individuals differ in many respects, and a sizable number of students hold values so difFerent from those described that no one could recognize them in the composite. Many of these deviators from the norm, these individuals who do not conform to the student stereotype, are potential recruits for a venture in the development of moral responsibility. Some are already at the forefront of responsible student leadership. Some are caught in a tangle of inward tensions which block creative effort. They are a lonely minority, often tagged with the label of 'odd-ball.' The mark of their oddness is more likely than not to be their readiness to join causes and otherwise demonstrate interests beyond themselves. The fact that such are identified as the odd ones simply confirms what is the prevailing pattern."

The Dartmouth Alumni Magazine hopesto print in next month's issue the fulltext of Professor Jacob's address.

Professor Allport

I HAD the privilege of teaching for four years at Dartmouth. As a matter of fact, I had the special honor of teaching your President psychology. But while my subject at that time was and still is social psychology, I cannot recall a single dis- cussion group that we had in those years on the problem of discrimination or prejudice. I don't think anybody thought about bringing it up.

"Now conditions have changed very, very drastically. I find that it is a subject of considerable concern on the Dartmouth campus, as it is indeed in the nation at large and the world at large.... What's happening on our campuses is only a reflection of what is going on in the nation.

"Discrimination is the act of placing some groups of people at a disadvantage in respect to voting rights, housing, transportation, recreational facilities, education, or admission to social clubs. . . . Prejudice has two ingredients. The first is a feeling state. You can be prejudiced for or you can be prejudiced against. Spinoza speaks of a love prejudice or a hate prejudice. But much more important is the second ingredient. Prejudice is a matter of false generalization, or of false categorizing - usually over-categorizing. The best single definition that I have run across that has these two ingredients in it is from St. Thomas Aquinas. St. Thomas, or at least one of his translators, has phrased it this way: 'Prejudice is thinking ill of others without sufficient warrant.'

"Everything of these matters that has been discussed recently has a tremendous international significance. Why should a local campus problem, or our personal prejudices, or Little Rock, or anything else have a bearing upon America's place in the world? Well it does, and I can speak with some feeling because in Africa the situation was clear to me. The colored races that comprise three-quarters of mankind are watching very closely. They are wise and they know perfectly well that our American creed is ideal. They love the Declaration of Independence and our democracy as much as we do. They know what it is and they also know the details about school integration. They also know that communism promises equality too. . . . And which are they going to believe? They're listening and they're watching. Therefore I say with the utmost sincerity, we have a limited time to make the American creed work. We have a limited time to make it seem not hypocrisy. That is the knife edge we're balancing on. They don't expect it to be solved overnight, but they do expect firm, steady progress and living up to protestations. * * *

"What does that have to do with the campus? Only the obvious moral: If we cleaned up our own neighborhood, whether it be a fraternity, campus practices, or literally our home neighborhood, then the national scene would clear and the international scene would greatly improve; and America's relations in the world would move toward equi-mindedness, order, and peace."

Mr. Mumford

PERHAPS the ultimate challenge to American democracy is, are we still capable of a critical self-examination? Have we enough detachment, enough courage, to stand off and look at ourselves and understand where we are and what we are doing, where we are going?

"The founding fathers of our country were keenly aware of democracy's checkered history. But. . . our fathers more or less took the moral basis for democracy for granted. Their main efforts were to give our governmental institutions sufficient flexibility to provide for a concentration of power in emergencies and a redistribution and dispersion in normal conditions. In particular they guarded against central authoritarian control over the channels of information and communication - anything which could limit intelligent public appraisal, curb public criticism or stifle moral judgment and protest. The new protestant heresy, the right of private judgment, was the ultimate safeguard against collective or governmental pressures; and that remained the foundation stone of American law and American morality. * * *

"But for all their historic insight and their historic foresight as well, the framers of our Constitution could not foresee the changes that have actually taken place in our day. And it is these changes that constitute the main moral challenge, it seems to me. . . . Our founders could hardly anticipate that effective political and economic power would be sucked out of the local communities and small groups and be drawn into the great monolithic organizations, mechanical collectives, business corporations, trade union organizations, and political and military bureaucracies. They could not anticipate that such organizations, commanding vast energies and productivities, would establish the mass standards for a mass society, mechanically operating in a moral vacuum. Even less could they have believed, in advance of the fact, that in these circumstances large areas of our central government would pass out of all popular surveillance and control and would operate in secret, defiantly withholding and adulterating the information needed by a democracy in order to pass judgment on the work of its offices. * *

"But all these things have happened in our time; and they have taken place without effective democratic resistance because the very organs of our response, our residual democratic groups, have gone the same way; and our own personalities, each and every one of us, have been affected. We have passed so smoothly that we have hardly marked the passage into an increasingly totalitarian mass society, sometimes called, in all too blatant imitation, a people's capitalism. * * *

"By and large the most vital issues that confront our democracy have not been discussed and, under the kind of private and governmental supervision exercised in our mass media of communication, there is little likelihood that they will be. * * *

"Without men, without morally responsible men, democracy cannot live. We need men at the bottom as well as at the top - vigilant men, ready to challenge the totalitarian processes and the autonomisms that have gotten out of hand.... The only way to govern large organizations apart from decentralizing them and giving greater autonomy to local groups is to insert active human agents, trained to register human responses and make moral decisions at every point in the whole process, people capable of answering back.... We need audacious, self-respecting men, ready, as the Quakers say, to speak truth to power, able to intervene in every automatic process ... or to change to goals themselves."

Mr. Taft

CHARLES P. TAFT, former mayor of Cincinnati and vice-president of the National Council of Churches, spoke on the involvement of individuals with community affairs, a concern which he considered much more rewarding and more in step with Christianity than just a narrow drive toward self-advancement. "This is where William H. Whyte in The OrganizationMan went too far," he asserted, "by im-plying that you should stay away from the big organizations."

He further stated, "You can't get away from self-advancement when you go into the world, but don't let it become the most important thing. You have to submerge yourself in some community goals in which you believe; you must lose yourself to an extent in groups that do something for the community. In these groups you will find good, solid satisfactions."

Mr. Taft felt that "most churchmen today give wholehearted support to capitalism and self-advancement." However, he opposed such doctrines, feeling that these churchmen preach Plato and not Christ. "Christ is just the opposite," he stated. "These Platonic teachings are self-centered and that's the trouble with them. They are not Christianity, and they are not democracy. The Christian teaching is not a self-centered striving for immortality. It teaches us of God's love pouring down on all. This is a tough point, and we don't think it is quite right at times. But this is Christianity, and the important question is how do we respond to it."

Dr. Eddy of the University of New Hampshire and Prof. Underwood of Wesleyan leading a discussion of the moral aspects of teaching.

Another group discussion, on discrimination on the campus, was led by Prof. Allport of Harvard (center), former Dartmouth teacher.

Rev. F.W. Alden '19, Dean Jensen and Dr. Van Dusen at the installation ceremony.

Lewis Mumford, who gave the main address.

Charles P. Taft in 105 Dartmouth Hall.

Prof. Jacob talks with student delegates.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

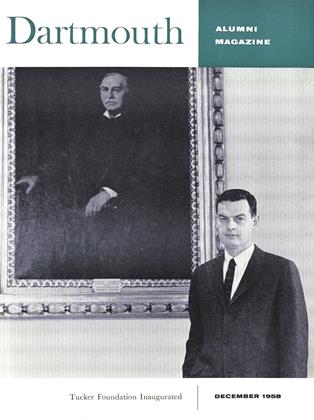

FeatureDARTMOUTH and DARTMOUTH

December 1958 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

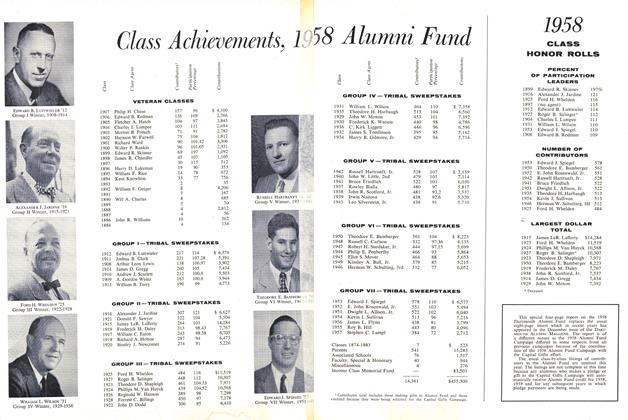

FeatureClass Achievements, 19

December 1958 -

Feature

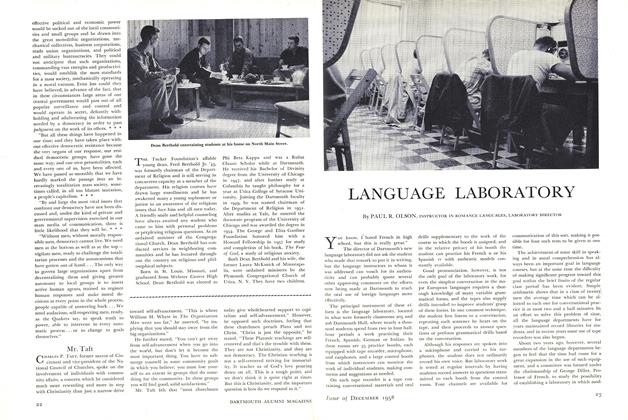

FeatureLANGUAGE LABORATORY

December 1958 By PAUL R. OLSON, INSTRUCTOR -

Feature

Feature1958 ALUMNI FUND REPORT

December 1958 By William G. Morton '28, -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI FUND PLANS FOR 1959

December 1958 By Donald F. Sawyer '21, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1958 By THOMAS E. SHIRLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE1 more ...

Features

-

Feature

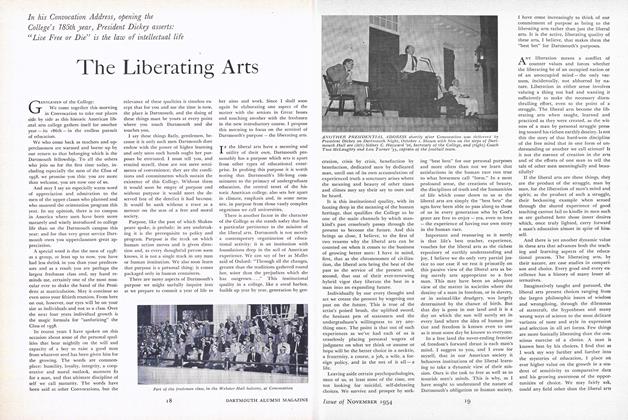

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureA New Look for Reunions

JULY 1966 -

Feature

FeatureA Landmark Goes Down

OCTOBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureMan and His Environment

JUNE 1971 By ALVIN O. CONVERSE -

Feature

FeatureThe Greatest Issue: Self-Fulfillment

July 1962 By JAMES T. HALE '62 -

Feature

Featurenotebook

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By VOSS/REDUX STEPHEN