By John Wilmerding (Associate Professor of Art). With an Introduction by Charles D. Childs. PeabodyMuseum of Salem and Boston PublicLibrary, 1971. 123 pp. $20.

It has long been the custom to regard pictures of ships as of interest only to spraysoaked zealots who value above all a tedious exactitude. There are reasons, such as the thousands of gawky "owners' portraits" of particular vessels, sailing broadside to the viewer across rock-candy waves. Yet the same sort of patron-coddling delineation makes nearly all portraits of persons just as dull. Only a few emerge as anything more notable than laborious likenesses.

Seven or eight years ago Professor John Wilmerding began his one-man campaign to convoy overlooked American painters marines out into the main stream of our art He did so first, and with decisive competence, for Fitz Hugh Lane. His new book jogs back a generation further to the more difficult subject of British-born Robert Salmon, who spent his highly productive last fifteen years mostly in Boston. Here again Wilmerding demonstrates what should have been self-evident: that any picture's distinction rests upon its own merits as a creative performance, whether its subject is afloat or ashore, outdoors or in. Fifty-six plates-six of them in color— have been excellent; selected to support his thesis. We get in addition a hitherto unique bibliographical resource: the first printing of the Boston Public Library's script copy of Salmon's probably lost inventory giving some information upon nearly 400 of his oils and drawings. A diligent job of newspaper scanning has produced also a perhaps complete record of auction sales and exhibitions.

Except for Salmon's catalogue there is no evidence of a search in manuscript archives for the one thing I miss in an otherwise exceptional performance: a sense of this important painter as a human being. Perhaps there is nothing to be found. Unfortunately, the author himself feels the lack and has tried to compensate with information about the purchasers of his subject's pictures that is superfluous and sometimes wrong. He tells us (page 45) that Thomas Handasyd Perkins "was elected to the United States Senate eight times between 1805 and 1829"—a self-evident absurdity. Perkins was never a U. S. Senator. There are other evidences of haste on the periphery. It is stated on page 28 that William Falconer's Shipwreck, one of Salmon's sources for pictorial ideas, "was first published in 1806." The Philadelphia edition of 1774 (not the first by twelve years) is in Baker Library.

Senior academic types,' by gleefully exposing such unimportant lapses, are supposed to buffet their juniors into a reverence for precision. That is not really my purpose, so much as it is to urge John Wilmerding to steer clear of surrogates for his best talent, which he uses in the last three chapters with confident authority. The earlier chapters tend to be repetitive. What they present of real fact is valuable, but it does not need to be stretched by such speculations as this: "in 1837 he was able to paint no more than ten pictures, none of which seems to have been sold. Conceivably he took sick, or made an unaccounted trip home." (Page 41.) I think there is a definite explanation in the financial panic of that year, which wiped out the fortune of one of Salmon's best customers. Robert Bennet Forbes.

Except for a few references to dories in paintings that display no dories at all, I can find nothing to grouse about in the second half of the book, where Wilmerding's aesthetic soundness as a critic and brilliance as a teacher strongly emerge.

Retired Dartmouth Professor of BelleLettres, Emeritus, Mr. Laing is the well-known novelist, poet, and essayist. His latestbook, "American Ships," has just beenpublished.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

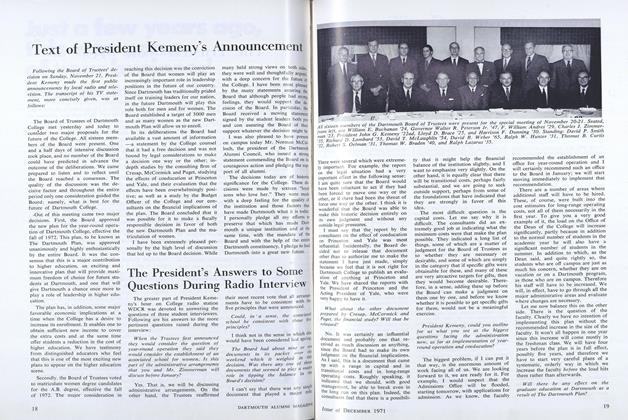

FeatureSome Views About Dartmouth Athletics From the Man Who Directs the Program

December 1971 By Clifford L. Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

December 1971 -

Feature

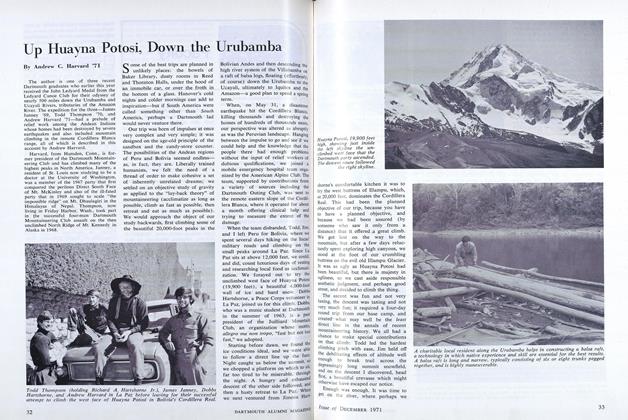

FeatureUp Huayna Potosi, Down the Urubamba

December 1971 By Andrew C. Harvard '71 -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees Vote "Yes"

December 1971 -

Feature

FeatureText of President Kemeny's Announcement

December 1971

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Books

BooksUNDERCLIFF. Poems 1946-1953.

May 1954 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksEUGEN ROSENSTOCK-HUESSY: BIBLIOGRAPHY-BIOGRAPHY.

December 1959 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleVirtuous Pagan

January 1960 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksCOLLECTED POEMS 1930-1960.

February 1961 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleBelinda

MARCH 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksFITZ HUGH LANE.

MARCH 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Notes

October 1947 -

Books

BooksMORE THAN MERE LIVING,

May 1940 By F. L. Childs '06 -

Books

BooksCHRISTIAN FAITH IN BLACK AND WHITE: A PRIMER IN THEOLOGY FROM THE BLACK PERSPECTIVE.

May 1974 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45 -

Books

BooksKAZANTZAKIS AND THE LINGUISTIC REVOL UTION IN GREEK LITERATURE.

JUNE 1973 By KATHERINE LEVER -

Books

BooksDEMOCRACY IN A CHANGING SOCIETY.

NOVEMBER 1965 By WALDO CHAMBERLIN -

Books

BooksBASIC DATA OF PLASMA PHYSICS.

January 1960 By WM. P. DAVIS JR