By Richard Eberhart '26. New York: OxfordUniversity Press, 1960. 228 pp. $6.00.

Two of Dick Eberhart's previous books are designated in their titles as "Selected" - which may explain the failure to use the same word again for this, a third and a larger selective gathering. Younger readers who are fascinated by his recent work should have a chance to acquaint themselves with the poet's substantial first book, A Bravery of Earth, here represented by only three pages of excerpts. A volume properly entitled "collected" should include it. And yet there is no eminent recent poet whose work in the long view stands more in need of selection. Dick has been ungovernably productive. Friends of his who share a strong hope of his ultimate endurance as a major figure in poetry share also a deep worry over the seeming failure of selfcriticism which permits him in the first place to put such terse, miraculous poems as "Rumination" and "'I Will Not Dare to Ask One Question'" in the same book with the prosy and lumbering "Of Truth." From the book in question, Burr Oaks, nine of the thirty poems have been omitted. It is comforting to be able to agree that all of these should have gone, and that "Of Truth" has not survived into the newest selection. But "The Ineffable" has, and it has always seemed to me to be just that, in both the primary and the variant senses: it deals with what is "incapable of being expressed in words" (I quote Webster) and demonstrates the proposition.

A sequential reading of this new selection does give encouraging evidence that a greater concentration upon the poet's durable virtues, is under way. It seems to me that Dick's chief talent is for a ruthless kind of metaphysics that uses concrete symbols: the lamb, the tree in the arm, the groundhog. His perilous flaw is pure abstraction. He loves, as a poet ought to do, all the great central words, but he tends in many poems to use them in a lax context, with the result that the meaning is hopelessly indefinite.

There could not be a better exercise in contrast of method and effectiveness than the two last poems in the volume which I have reread with care for the purpose of judging the principle of selection: BurrOaks. "At the End of the War" is, a long abstract exhortation which succeeds in saying only a fraction of what is conveyed in the much more restrictive scene of the following, somewhat shorter "A Ceremony by the Sea." Both survive among the present selections. Dick knew that the latter was the better, because he chose it to close the earlier volume. He does, not seem to realize how remarkably it is the better.

"The Moment of Vision," which after many readings seems still the most successful of Dick's forays toward the ineffable, may be his poetic credo, the justification for his evident trust of the inspirational moment, unexamined. It contains lines as different in quality as, In this pleasurable though unpredicable predicament and Went up through hitched forests to a gold plateau.

The fifty-one new poems reveal a continuation of the puzzling variation of quality. This time the last poem, "The Incomparable Light," presents the same dilemma of the ineffable; but another near the end, "Equivalence of Gnats and Mice," is - despite a small grammatical problem — on the level of Dick's beautiful, metaphysical best. That is to say, the level of the best poetry now being written by anyone.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dollop of Yankee Talk

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeatureNow They're Flicks, Not Movies, But The Nugget Still Carries On

February 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureDr. Myron Tribus of UCLA Named Dean of Thayer School

February 1961 -

Feature

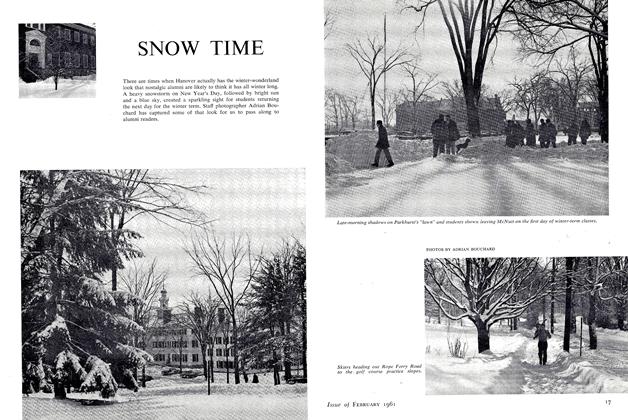

FeatureSNOW TIME

February 1961 -

Article

ArticleProblems of Land Development in the New African Nations

February 1961 By BARRY N. FLOYD,

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleHakluyt in Hanover

October 1939 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleCOLLECTED VERSE PLAYS.

JANUARY 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksNOTES FROM A BOTTLE FOUND ON THE BEACH AT CARMEL.

APRIL 1964 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksTHE STRIDE OF TIME.

APRIL 1967 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksFITZ HUGH LANE.

MARCH 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

June 1917 -

Books

BooksTHE ISLANDS

June 1936 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksGAUGING PUBLIC OPINION

June 1944 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Books

BooksECONOMIC PRINCIPLES IN PRACTICE

June 1939 By G. W. Woodworth -

Books

BooksTHE CUBAN FISCAL SYSTEM,

February 1940 By J. M. McDaniel -

Books

BooksHOW TO LIVE LIKE A RETIRED MILLIONAIRE ON LESS THAN $250 A MONTH.

November 1968 By JOHN HURD '21