It means a slowdown in growth,but not a cutback in quality

The colleges and universities of this country have a long-standing acquaintance with financial problems, and over the years they have developed a certain adeptness in wrestling with them. But nothing in past experience has prepared them for the severity of the financial crunch that exists today and is predicted to get worse; nor have so many institutions, including even the richest, ever before been involved in the hard times that have overtaken U.S. higher education with a rush in the past two years or so.

Reports of actual or projected deficits running into the millions have been coming from some of the country's leading universities, but it was the December report of the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education that presented the crisis in its true dimensions by disclosing that two-thirds of all U. S. colleges and universities are in financial difficulty or are on their way to that critical state. Shortly after the Carnegie study was made public the Association of American Colleges released its estimate that deficits at independent colleges for the four- year period 1967-1971 will total nearly $370 million. The financial troubles of American higher education today are clearly serious and widespread, and everyone expects them to get worse next year.

Dartmouth College is not immune to the prevailing financial pinch. At a general meeting of the Dartmouth faculty in January, President Kemeny reported that the problem here is "serious but not catastrophic." Much depends this year on achieving the Alumni Fund's stepped-up goal of $2.5 million, for that amount will enable the College to balance its books. For next year, the Trustees have worked out a strategy they are counting on to avoid a projected deficit of at least $500,000.

Dartmouth's financial problem, while serious enough m relation to the College's resources, does not at present or for the immediate future appear to be as critical as the problems faced by her sister universities in the Ivy League, Harvard possibly excepted. Princeton, for example, expects to run a deficit of $2.5 million this fiscal year, on top of a $1-million deficit last year. In order to reduce what would otherwise be a $5.5-million deficit next year, Princeton has announced higher tuition fees (as has Dartmouth and nearly every other college), a cut of 100 persons from its payroll, and "severe restraints" on faculty salaries.

Columbia has announced a five-year program to eliminate its current operating deficit of $15.3 million. Drastic curtailment of services and programs has been announced for the coming year, and a cumulative cut of 15% in these categories through the fiscal year 1973-74 is planned in order to arrive at a balanced budget by that time.

The Yale trustees, after a two-year deficit of $4.3 million, have ordered a $5.25 million cut in the 1971-72 budget in order to reduce what would otherwise be a deficit of $8 million. And since that decision, Yale has announced a $500 increase in the annual student fee and a plan that allows students to defer part of their tuition for as long as 35 years in return for a fixed percentage of future annual income. The payment of as much as $100 a year can be postponed, and for each $1000 deferred the student would contract to pay back 0.4% of his annual income over a maximum of 35 years.

Cornell's current deficit is reported to be $2.5 million, Brown's $1.8 million, and Pennsylvania's $1.3 million. Even Harvard, with its huge investment portfolio of $1.3 billion, is struggling with the gap between costs and income, and a special study committee recently described the university's financial outlook as "dismal."

The big problem for all colleges and universities caught up in what the Carnegie Commission report calls a "depression" for higher education is that costs are rising at a steady upward rate while income is growing at a declining rate. Inflation and the economic downturn, which has reduced both gifts and investment revenue, have been two prime factors in the financial tailspin. And universities that have been getting a substantial part of their operating income through federally financed programs have been hard hit by the cutback in government funds for education and research. Dartmouth can take some comfort in what turns out to be the good fortune of not having gone in very heavily for federally financed programs.

The Dartmouth Situation

Assuming that the 1971 Alumni Fund will fulfill the crucial role assigned to it and make it possible to balance the 1970-71 books, the pressing financial problem for the College is what to do about the coming year, and the year after that. The strategy approved by the Trustees can best be described as one of "slowed growth." It can be carried out, President Kemeny says, without adulterating the quality of Dartmouth's educational program.

Over the past 17 years, Dartmouth's budget has had an average annual increase of 11%. In addition to great improvement in faculty and staff salaries, the introduction of new programs, and the building of new facilities, it is estimated that 3% of that annual increase came about through inflation, and 1% through larger enrollment. There also was a sizable growth of the faculty, which in the last ten years has increased from 210 to 285 (or 36% ) for the Faculty of the Arts and Sciences. For the general faculty, including the associated schools, the growth of 50% has been even greater. More generous financial aid, involving a rising percentage of the student body, has also been a factor in the annual 11% increase in the budget during the past 17 years.

The 11% growth each year was financed by steady annual increases in endowment income, up 9½%; student fees, up 9%; the Alumni Fund, up 9½%; gifts for current use, up 12%; and sponsored activities, including those federally supported, up 25%.

For the current fiscal year, that growth rate has been reduced to 6.6%, and in order to accomplish that much, free funds will have to increase over last year's by 10.8%.

The College is prepared for harder times next year. One factor being taken into account is an expected drop of $200,000 in endowment revenue. Last year for the first time the College used the total-return concept, which combines the dividend and interest yield on endowment with a prudent portion of any capital gains, figured on the basis of three or more prior fiscal years. The downturn in the stock market will adversely affect the College's total return from investments next year. Along with this, the free funds earmarked from the first capital gifts campaign are being exhausted this year, and funds that have been supporting the Kiewit Computation Center are also being exhausted in 1970-71. These three items mean $450,000 less income. Higher costs for Social Security, postage, oil and a host of other things jump the deficit to an estimated $570,000 before faculty and staff compensation enters the picture.

To meet this upcoming problem, the College has announced a $270 increase in tuition next year (from $2550 to $2820), along with a $50 increase in board (from $740 to $790) and a $35 increase in the average room rent (from $534 to $569). It has been decided to expend in four years instead of five the $5-million component of the Third Century Fund that was designed to provide general-use funds until the Third Century Fund could be fully collected and become fully effective in the financial operations of the College. Hopes are also pinned on a resumption of the annual growth of the Alumni Fund, which leveled off during the three years of the TCF campaign.

In announcing next year's increases in tuition, room, and board, President Kemeny stated that the College's financial aid policy will continue to help students to meet the burden of these higher charges; but in order not to have too large a part of the tuition gain wiped out by increased financial aid, as has happened before, a greater portion of the additional aid this time will be in the form of "self help" (loans and jobs). Over the past three years, as College charges have risen and the equal opportunity program has expanded, the total amount of scholarship awards has increased from $1.31 million to $2.33 million, and the number of undergraduates getting such grants has grown from 879 (28%) to 1180 (36%). An increasingly larger percentage of scholarship money has had to come from the College's unrestricted funds—57% this year compared with 42% three years ago—and it is for the purpose of slowing this down that loans will play a larger part in the upward adjustment of financial aid for the coming year.

In outlining the steps taken to help meet the deficiency in next year's income, President Kemeny at the general meeting of the faculty in January also announced that as important parts of the College's financial strategy there would be a slowdown in faculty salary increases for a two-year period and that there would be a relatively small reduction of from five to seven members in the Arts and Sciences faculty, brought about by the attrition of retirements and departures for other reasons.

In the new salary policy, President Kemeny specifically exempted the college staff, such as secretaries and clerical and maintenance employees, whose pay scales he pledged to raise in his inaugural address one year ago. Senior faculty members and administrative officers could expect normal salary increases for the coming year, he said, but there would be no increases the year following. During the years of economic stringency salaries will be reviewed on this two-year basis rather than every year, as in the past. For faculty below the rank of associate professor the policy of annual salary review will be continued, but raises will be less than in recent years. It is possible, President Kemeny added, that in some cases these annual raises might not be large enough to meet the rise in the cost of living, should the current inflation go on unabated.

As part of the slowing growth, he said, normal replacement hiring would be conducted in line with the reduced size of the Arts and Sciences faculty, and unfilled vacancies would be utilized to adjust faculty-student ratios within departments.

"I want to stress here," President Kemeny said in his faculty talk, "that what we're talking about is a slowdown in the rate of growth. We are not cutting back, which could only be achieved at the expense of the quality of the educational programs at Dartmouth. That, as I have said before, I would strenuously oppose."

Closing on an optimistic note, he recalled that periodically in its 200-year history Dartmouth has confronted serious financial troubles and has always prospered in adversity and come out stronger than before. "I have every confidence," he said, "that when we weather this financial storm, we will once again be stronger and better."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureART AT NOON

March 1971 By PETER D. SMITH, -

Feature

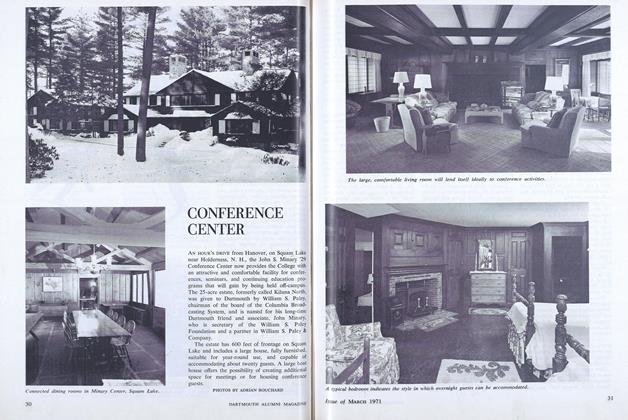

FeatureCONFERENCE CENTER

March 1971 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1971 By LAWRENCE G. MANLEY '71 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

March 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1971 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

March 1971 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

JULY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1970 -

Cover Story

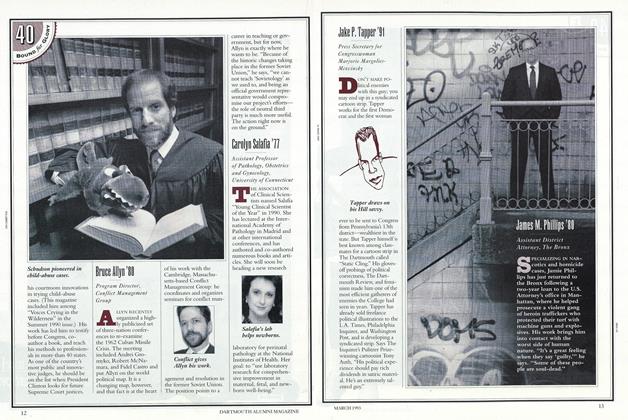

Cover StoryJake P. Tapper '91

March 1993 -

Cover Story

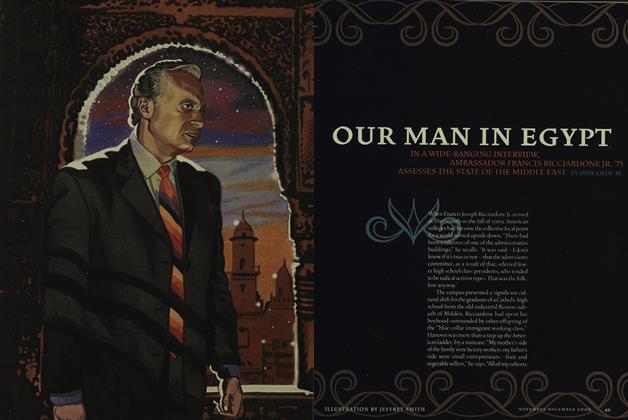

Cover StoryOur Man in Egypt

Nov/Dec 2006 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Cover Story

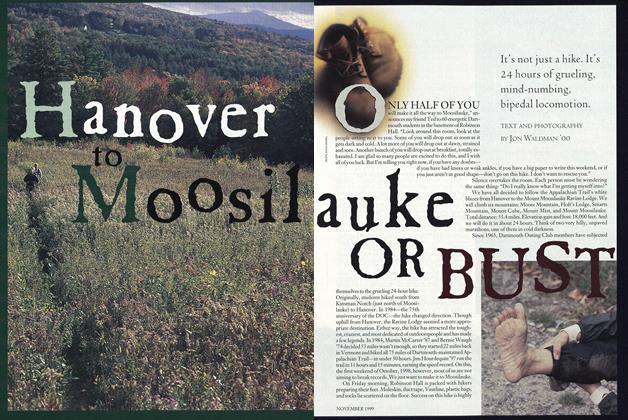

Cover StoryHanover to Moosilauke or Bust

NOVEMBER 1999 By Jon Waldman ’00 -

Feature

FeatureTaking God's Word For It

APRIL 1990 By Karen Endicott