During the past few weeks there has been a good deal of discussion on campus about maintaining the "quality" of the Dartmouth education without driving the College, parents, and students into bankruptcy. And most often the conclusion seems to be that the College, faced with increased operating costs and rising inflation, will soon be forced to consider making radical changes in the style, and implicity in the quality, of the education it offers its students.

In recent years the College has, like most others, become an inflationary casualty; in the past decade operating costs have risen at a rate of 11 per cent annually. Fortunately, however, the effects of the national economic crisis on the quality of education and student life here have so far been negligible.

Several recent developments, however, indicate that the student at Dartmouth will soon be feeling more and more of the impact of the College's financial burdens. The latest tuition hike, announced following the January meeting of the Board of Trustees, together with increases in room and board charges, raises the student's total average cost to $4179 per year.

While most students recognize the necessity of the increases, many will now require more financial aid, especially poor students in the Equal Opportunities Program. That program has become an unquestionable asset to the quality of education here, and has thus far been more successful than even 'he most optimistic observers had predicted. Although President Kemeny has pledged the continued expansion of the program for at least two more years, there may soon be a limit to the number of underprivileged students the College can support. A discontinuation or reduction of the Equal Opportunities Program would be a major loss in the quality of student life, but there has been no assurance that the program will be financially feasible if present economic trends continue.

At the same time, increased costs and requisite increases in financial aid for poor students are creating special burdens for middle-class students, who now face the possibility of being priced out of the institution. The establishment of long-term loan programs, similar to the one recently adopted at Yale, under which the student would pay a small percentage of his income for the rest of his life, seems to be the only hope available for the middle-class student.

But a second impact on the student, more alarming than the increase in his tuition, is the possibility that he may soon be paying more for an education which will, at best, be only as good as the one he now receives. The limitation of College resources due to inflation presents the threat to the student and the College that many of the anticipated improvements in the quality of education here may no longer be feasible under the present concepts of plant use and academic scheduling.

The devaluation of the Third Century Fund is a prime reason for the threat. Although the TCF drive was an immense success in topping its goal of $5l million, it now falls far short of the College's needs after inflation. Inflation, decreases in federal spending, imprecise planning, and a 40 per cent increase in building costs since the drive was initiated have raised the estimates for the planned components from $51 to $80 million. As a result, many of the projects have been "shelved."

Ironically, many of the projects which have been shelved—the science center, the renovation of Dartmouth Row and Silsby Hall, construction of three levels of new stacks for Baker Library, a new dormitory and dining facility, the squash and handball courts, the ice arena, and two or three planned Third Century professorships—are the ones which have the greatest direct effect on the quality of undergraduate education.

Lack of funds for expanding the undergraduate program, however, presents an even more serious difficulty. At a time when 82 per cent of the student body and most of the faculty and administration agree that the addition of 1000 women to the College would greatly enhance the quality of education for everyone concerned, it may not be economically feasible to make such an improvement. Most alumni, and many students, are opposed to a reduction in male enrollments in order to maintain the present student body size, but with a lack of funds for the necessary plant expansion, the alternatives are limited. The result may merely be an education which is more expensive, but not much better.

Therefore, the College is on the threshold of making a few major decisions which will drastically alter both the style and quality of student life. There seem to be two basic alternatives. First, the College may tighten its belt a couple of notches and head into the storm in an attempt to maintain the present quality of the Dartmouth education against an economic background which has yet to brighten.

This approach, often referred to as the College's period of "stability," would limit expenditures while retaining the features seen as advantageous, such as the small-college atmosphere, and a good student-faculty ratio. But there is no assurance that this approach, highly contingent on the national economy, will work. Already there have been small faculty cutbacks, and some new positions for next year will remain unfilled. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that there will be no more tuition increases, and no guarantee that programs such as the Equal Opportunities Program will be able to survive the financial crisis.

The second alternative involves a sweeping change in the whole "style" of the Dartmouth education in order to retain its present high quality. Basically this proposal, formulated by the Committee on Educational Planning (CEP), involves a 25 per cent increase in the size of the student body, with students attending the College on a year-round rotating basis, making full use of the Summer Term. In effect, the size of the student body on campus during any one term would not be significantly increased, while greater revenues would permit al2 per cent increase in the size of the faculty, and would hopefully alleviate other financial burdens. In addition, the 25 per cent increase in student enrollment could easily consist of women, avoiding the decrease in male enrollments which would be required in the maintenance of the status quo.

The primary justification for this change in the "style" of the Dartmouth education seems to be that such a change is the only way of maintaining what is considered the "quality" of the present system, i.e:, small student body, good student-faculty ratio, uncrowded facilities. Thus far the debate has centered around the problem of procedure, often without a genuine reexamination of the concept of a quality education.

Under the CEP proposal, however, changes in the quality of education are implicit in changes of style. By spending several terms away from the College, for instance, the student would have an opportunity to examine his future plans, and the relation of his college career to those plans. There would be a greater opportunity for flexibility in the planning of a student's educational program.

In addition, by spending consecutive terms away from the College, the student would have better opportunities for obtaining gainful employment in financing his education. Long-term research projects and honors work would become more feasible, and hopefully more common.

Finally, the proposal would require that a student spend at least one term engaged in an off-campus project, such as the Foreign Study Program, or a teaching internship under the Tucker Foundation. The success of these off-campus projects in the past underlines their value as a potential integral part of a Dartmouth education.

Not all of the qualitative changes seem favorable. Many students, for instance, view the proposal for a rotating student body with suspicion. One of the chief complaints of transfer students and students returning to the College after a leave of absence is the sense of "rootlessness" they develop. Under the CEP plan lasting friendships would admittedly be interrupted, and perhaps difficult to form. The phenomenon of the closely knit College community and that thing sometimes called the "Dartmouth fellowship" might be threatened.

These implicit qualitative changes, which may be economically imperative in the future, point out the incongruity of a discussion of changes in style which does not involve a reevaluation of the concept of "quality."

Most students would agree that without a major improvement in the national economy, more cutbacks and tuition increases are imminent. And it may happen that very soon the simple advantages of uncrowded facilities, a sense of community, and an available teacher will no longer be worth the price. Having reached the point where economic burdens are directly affecting the student, it now seems time to reevaluate our concept of quality. In a day when we are poor despite our wealth, perhaps we have to look elsewhere for our dollar's worth.

Linda Appleton of Wellesley College is crowned Dartmouth Carnival Queen byDean Carroll Brewster at the ice show. Linda is the daughter of Arthur I. Appleton '36 of Northbrook, Ill., and the sister of James K. Appleton '70.

This year's center-of-campus snow statue was a full-rigged clipper ship.

"Thirst for Knollege" won the fraternity prize for Alpha Chi Alpha.

It was rainy and misty but the Winter Carnival jump went off on schedule.

Eric Kankainen '72 running the slalom.

Don Cutter '73 in the same event.

Dartmouth jumpers in the Carnival meet were (from left) Ken Stowe '74, AndyWexler '74, Glenn Roundy '74, Captain Teyck Weed '71, Don Cutter '73, GeorgePerry '72, Tom Kendall '72, and Dick Trafton '71.

Larry Manley, who comes from Belmont, Vermont, is an honors student inEnglish and during the past year hasbeen Executive Editor of The Dartmouth. He plans to do graduate workin English next year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE FINANCIAL CRUNCH

March 1971 -

Feature

FeatureART AT NOON

March 1971 By PETER D. SMITH, -

Feature

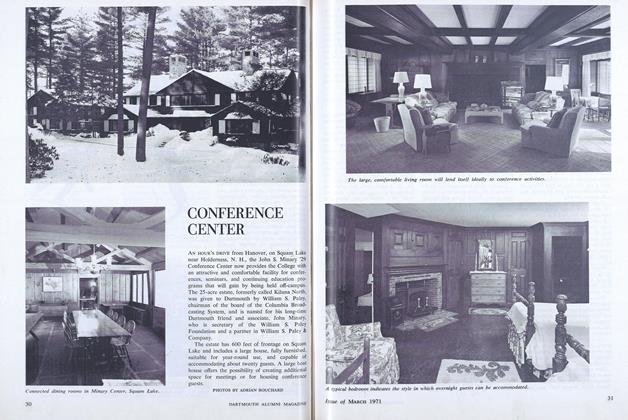

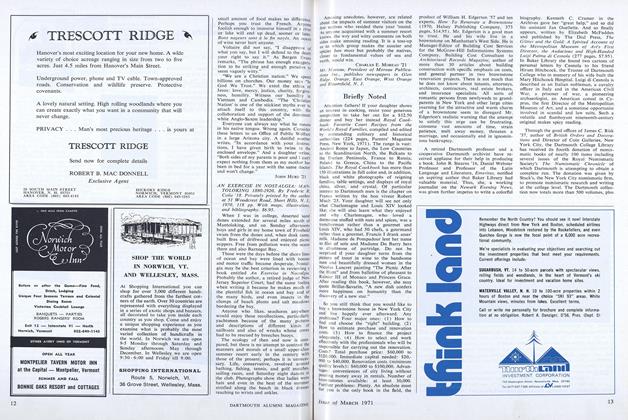

FeatureCONFERENCE CENTER

March 1971 -

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

March 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1971 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

March 1971 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, C. HALL COLTON

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE STATE OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

August, 1911 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Vacancies

February 1941 -

Article

ArticleArthur R. Upgren Named New Dean of Tuck School

February 1953 -

Article

ArticleBriarcliff President

January 1960 -

Article

ArticleChanges

SEPTEMBER 1988 -

Article

ArticlePROF'S CHOICE

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Professor Blanche Gelfant