A five-year project headed by Prof. Wayne Broehl of Tuck School seeks to activate entrepreneurs to advance India's economy

The key to India's future is to be found in the same people who gave history's highest standard of living to the Western World—the entrepreneurs.

This is the belief of Wayne G. Broehl Jr., Professor of Business Administration at the Tuck School. And, like an academic David confronting the Goliath of India's poverty, he has set about to help India find and harness the power, the leverage of those special entrepreneurial people who can make the difference.

Actually, of course, his primary purpose is research, a five-year project undertaken by Dartmouth and Tuck School in collaboration with four graduate schools of management in India and supported by the Ford Foundation. But it is his hope and his conviction that his research may be helpful in practice as well as theory.

The Ford Foundation and the Government of India share this hope. Both are encouraging Professor Broehl, an authority on social issues facing business in this country and in less developed nations, to report his findings wherever possible over the five-year time span of the project so that any insights he gains can be put to work immediately in the overall effort to break the vicious cycle in India of poverty, underemployment and unemployment, illiteracy, and ignorance.

The project began because Professor Broehl asked himself the question: Can the key ingredients of entrepreneurship be identified and isolated within the matrix of the economic, cultural, religious, and traditional forces in the Indian society, or any society, and, if so, can the inculcation of those characteristics be built into the nation's formal system of training?

The problems of India dwarf anything that can be conjured even under the term Herculean. A land about one-third the size of the United States, it teems with 550 million people, or more than two and a half times the population of this country. It is noteworthy for comparison that the industrial revolution in this country not only took hold before the population surge, it was fueled by a plentiful supply of natural resources and an important proportion of literate and trained people, whose own tradition was of breaking tradition and who were abundantly blessed with what since has been called the entrepreneurial spirit.

In contrast, India, still only 25 years from colonial status, has had to try to modernize in a land so crowded that it almost literally eats up surplus capital before it can be generated. Its traditions have been fashioned in part out of resignation and fatalism and a retreat to the world of the spirit reminiscent of Medieval Europe. In India, the entrepreneurial man has never been able, as here, to ride the crest of development, but has always had a steep uphill climb through thickets of cultural, religious, and economic obstacles discouraging all but the hardiest.

Now, however, Professor Broehl says, the "Green Revolution," triggered by the development of the "miracle" seeds of wheat, rice and other grains, is producing a ferment and an awakening of hope that could unleash the human energy required to put India on an upward track. The "Green Revolution," Professor Broehl contends, is buying a few years' time and giving the entrepreneur a chance to work his own secular miracle on top of that started in agriculture by lowaborn Norman Borlaug, whose breakthrough to new highyield grain won him the Nobel Peace Prize last year.

"India desperately needs new businesses developing on a vast scale," Professor Broehl argues, "but to get them it needs to know how to get businesses started, whether small businesses in the agri-business sector in which I am now working, or large enterprises in basic industries.

"But to get that lift, India requires a large infusion of entrepreneurs, purposeful and imaginative people with a will and a way for getting the world's work done."

Professor Broehl, who spent three years, 1964-67, in Latin America doing a comprehensive study of the entrepreneurial role there, cautions that there is a lot of loose thinking in India about who is going to produce innovation and growth. He stresses that, in his view, an understanding of entrepreneurship has become a fundamental need for Indian development today, the more so because, while India has produced some excellent business leaders who could hold their own with the most sophisticated anywhere, the notion of entrepreneurship is not yet in the Indian tradition.

Therefore, as Professor Broehl wrote recently, "A better understanding of this complicated business of comparative entrepreneurship could have a high payoff for mankind. The widening disparities between rich and poor around the world and the heightened concern about bringing low achievers into a state of higher achievement make this concern one of the most relevant of contemporary development questions."

In talking with Professor Broehl, it is clear that he is totally immersed in his project and even has involved most of the Tuck School faculty.

He first went to India in the late 1960's to visit a poultry breeding business in Poona, near Bombay, as part of his research on the 20-year history of the International Basic Economy Corporation (IBEC). IBEC is a corporation initiated in 1946 by Nelson Rockefeller '30 and now headed by his son, Rodman '54, to help provide, primarily in Latin America, the financial backing and organizational know-how required to start industries producing such basics as food, shelter, and clothing.

Professor Broehl, whose earlier comprehensive studies of the trucking industry and the troubles in the Pennsylvania coal fields dramatized by the Molly Maguires had resulted in two widely acclaimed publications, traveled to 35 countries in Latin America, Europe, and Asia in the course of his study of the impact of IBEC. That study is all reported in a 350-page book published in 1968 by the National Planning Association as the 13 th in its series on "United States Business Performance Abroad."

One of these places he visited was Poona, and there, according to Professor Broehl, "I got hooked by India" in a way that has added a deep personal involvement to his professional research interest.

After that visit, he made another in 1969 to test the feasibility of the entrepreneurial research project, which was taking shape in his mind, and then he went back again last summer, when he began his field study of the characteristics of rice millers and fertilizer distributors in Tamil Nadu, the semi-tropical agricultural state in India's southeast corner where much of India's rice is grown and some of its most exquisite Hindu temples are found.

As a result of those visits, he explains that "in a Paradoxical way, I really have come to love the place a kind of fatal fascination. I feel caught up in India and its problems and can't get her out of my mind. I've never known another country about which I've had such strong feelings beyond the United States itself."

He acknowledges that India also is probably the most difficult country in which he has ever worked. For instance, he had to overcome in his first summer of field work an intense and pervasive sensitivity about any foreign presence or encroachment, including what Indians now call the "academic imperialism" of western researchers. Meanwhile, his Indian colleagues are constantly slowed by snarls of exasperating bureaucratic red tape, made the harder to live with by the urgency of India's need for information.

"Many people are either repelled by conditions in India, or deeply depressed by the cultural shock that hits them in cities like Calcutta, where thousands literally live—and die—in the streets," he said. "Perhaps it is simply the magnitude and importance of the challenge and the impressive patience of the people in the face of it, but I know that for myself, as irritated as I can become, I am drawn to India and find it constantly intruding on my mind."

India did not get quite that grip on him during his first visit, but it did intrigue him enough to make him decide that India, not Colombia, as he had previously thought, should be the subject of an intensive one-nation study of entrepreneurship to complement his comprehensive study of IBEC and the entrepreneurial potential among the less developed nations of Latin America.

That notion also appealed to the late John Masland, former Provost at Dartmouth and then the Ford Foundation's educational representative in India, who was interested in breaking down the Indian tendency toward institutional compartmentalization.

It occurred to them that Professor Broehl's project would fit both purposes, if he could involve India's four leading management institutes in the research as collaborating and cooperating partners, pledged to share their findings with each other. Professor Broehl then won the participation of the two Indian Institutes of Management—-one at Ahmedabad northeast of Bombay with strong links to the Harvard Business School and the other across the subcontinent at Calcutta with ties to the Sloan School of Management at M.I.T.; the Birla Institute of Technology and Science at Pilani in the desert regions of Rajasthan, west of Delhi in north central India; and the Administrative Staff College in Hyderabad in south central India, patterned after the English administrative staff college in Henley.

In the summer of 1969, one research scholar from three of those institutes and two from the one in Calcutta—including two economic historians, a political scientist, a social psychologist, and a finance specialist traveled halfway around the world to join Professor Broehl at Tuck School in a two-month seminar on entrepreneurship.

Together, as an inter-institutional group, they formulated the nature of their overall "Entrepreneurial Research Project" and assigned parts of it to each of the six scholars—five men and one woman.

The assignments cover the Indian scene from West Bengal, where 35 million people live in a state the size of Maine (population: approximately one million), to Tamil Nadu in the south. While the Indian scholars have 18 projects, ranging from a survey of the history of entrepreneurship in India to an analysis of how technology is transferred to and adapted by industry in India, Professor Broehl was given the task of identifying what social and personality characteristics might make for entrepreneurship among rice millers and fertilizer distributors in two such differing areas in Tamil Nadu as the dry farming area around Madras and the rice growing delta of the Cauvery River farther south.

In preparation for this assignment, he even spent part of an exchange (sabbatical) year in 1969-70 at the Wharton School taking intensive language courses in Tamil at the University of Pennsylvania, while teaching at Wharton.

Thus, last summer, he surprised many of the Indian farmers and small businessmen with whom he spoke by being able to understand some of what they said and to speak to them in their native tongue, a factor that he feels went a long way in breaking down resistance to his research "prying."

While fighting off dysentery and the host of other problems that plague the westerner in India, he went about with an Indian research assistant for three months interviewing 47 fertilizer distributors and 30 rice millers to get answers to 86 basic questions on a questionnaire that eventually was broken out in coding to approximately 540 separate punches for each respondent, ranging from what each proprietor's gross sales and net profits were over a series of years to what education he had had and what papers he read, if any. A host of other questions posed basic attitudinal and personality questions about each man's philosophy of life and work.

He decided to concentrate on the agri-business sector for his phase of the study because the majority of the Indian people languish in the nation's 560,000 villages. Thus, he reasoned, if India is going to experience any genuine economic advance, it has to be in enterprises reaching these people in the rural areas, where underemployment and stultifying tradition are endemic He selected the rice millers and the fertilizer distributors because they are closely involved in the central industry of rural India, agriculture, one on the input side and the other on the output side, and both might have the potential to be true "agents of change" in the sense that they could introduce "new functions of productions creating jobs, goods and services that were not there before and thus an incremental advance in living standards.

In his first summer, Professor Broehl, who was accompanied to India by his wife and family, found out how little accurate quantitative information is available in India even when businessmen seek to cooperate, a factor that underlines his view of his research as a pilot project. Although he started with certain basic assumptions, he finds now that his project is in some degree still in search of a valid working hypothesis.

And to this end, he has found in the Tuck School faculty an invaluable resource. In an ideal instance of the kind of academic collaboration that is possible among a relatively small and tightly knit faculty, Professor Broehl's Tuck colleagues meet with him regularly either as individuals or as a group to help him assess his data and their implications. Thus, he finds important reinforcement in his mammoth undertaking from faculty bringing to his project the expertise from the several disciplines of management—from finance and marketing to organizational behavior to quantitative analysis. As a result of this kind of exchange, plus the chance to come back to Hanover and view India from the perspective of distance, Professor Broehl says he has a better feel of what to look for when he goes back this summer for round two of his field research. He will go back once again in the summer of 1972, and the entire project will be completed with a major conference either in India or at Tuck School in the summer of 1973 when he hopes there will be worthwhile findings to report.

Meanwhile, his project is having significant cross-fertilization right at home on the Hanover Plain. Professor Broehl, who sees the changes being wrought in India by the advent of "miracle rice," is joining Geography Professor Robert Huke, who last fall returned from a year of study at the International Rice Institute in Manila on the impact of "miracle rice" on the Philippine economy, and together they are preparing a new course called World Food Problems to be given by them jointly. To be offered to seniors in geography and second-year Tuck School students, the course will be the first interdepartmental course involving Tuck and a department under the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

For years, the dominant voices counseling the development of the less developed nations had been those of planners, mostly with strong socialist underpinnings. It is interesting to note that there are subtle and significant shifts in this thinking. Indeed, perhaps the most celebrated exponent of the theory underlying Professor Broehl's research is Gunnar Myrdal, renowned Swedish economist-sociologist and, ironically, socialist theoretician. In his mammoth book, The Asian Dilemma, which involved him in a dramatic reversal of preconception, Dr. Myrdal argues that rural capitalism offers the best hope for less developed lands.

Professor Broehl, one man based in small university in New England, is working with the Tuck faculty and his five Indian counterparts to give that entrepreneur—and India — a fighting chance in what might be called scholarship with an epic potential.

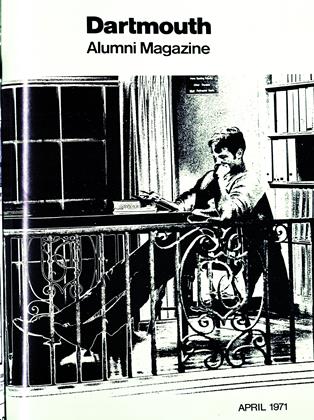

A rice farmer and his family ina typical village in Tamil Nadu. It is for the purpose of liftingthe standard of living for thesePeople of India that ProfessorBroehl and his colleagues arecarrying out their Ford Foundationproject.

An ancient plow (center) pulled by a bullock is still a standardfarming tool, but steel has now replaced wood.

"Miracle rice" requiresheavy use of fertilizer butthis is a hand process onmost of the farms through out India.

For irrigation of grainfields, farmers in Indiastill use the Picotah, aprimitive water-hoister onwhich men shift theirweight on the cross beam.

A householder drying rice on a mat on the village road, amethod entailing considerable loss from carts and birds.

Rice being hauled to the mill at about 1½ miles an hour.

Professor Wayne G. Broehl (right) withtwo of the Tuck School colleagues withwhom he has been analyzing the databrought back from India: (left) J. PeterWilliamson, Professor of Business Administration,and (seated) Victor E. Mc Gee, Associate Professor of Applied Statistics.Dartmouth's computer center isused extensively in the project.

An Indian rice miller of Tamil Nadu (center) who participatedin Professor Broehl's survey of data and attitudes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

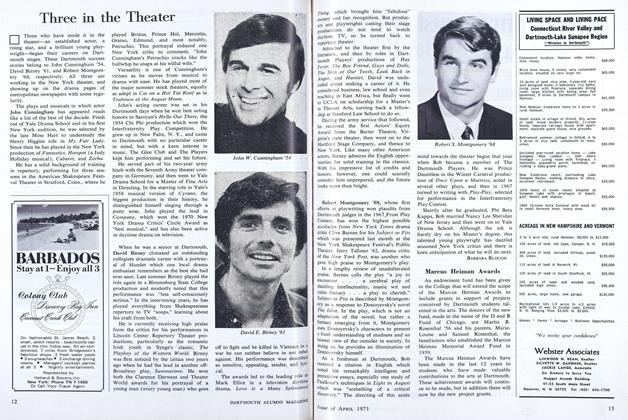

FeatureThree in the Theater

April 1971 By BARBARA BLOUGH -

Feature

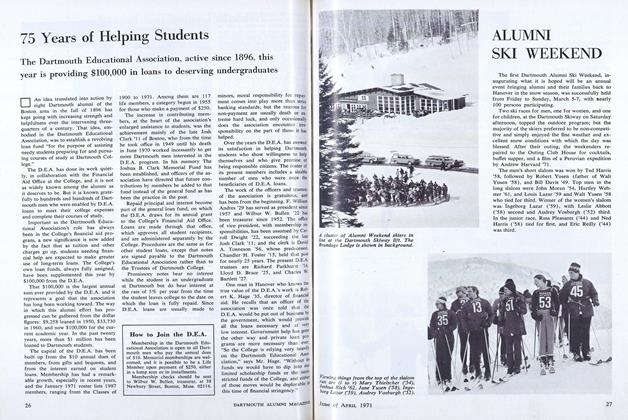

Feature75 Years of Helping Students

April 1971 -

Feature

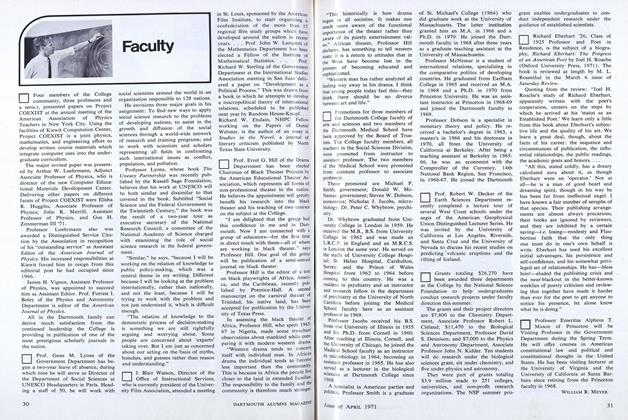

FeatureALUMNI SKI WEEKEND

April 1971 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1946

April 1971 By WILLIAM W. GRAULTY, JAMES E. O'NEILL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

April 1971 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, George Price

Features

-

Feature

FeatureConclave in Cleveland

March 1961 -

Feature

FeatureLive Free or Die

June 1992 By Ernest Hebert Viking, 1990 -

Feature

FeatureReflections

JULY 1966 By FLETCHER R. ANDREWS '16 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

JANUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

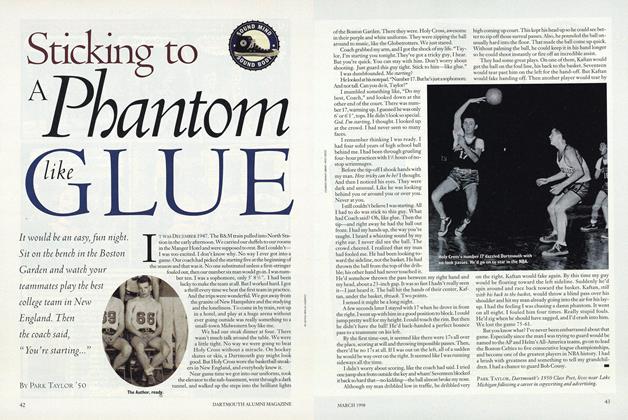

FeatureSticking to A Phantom like Glue

March 1998 By Park Taylor '50