PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

It all started because Alex Fanelli '42, Special Assistant to the President of Dartmouth, used to be in the State Department. Thus when the Fulbright professor who should have gone to Warsaw this past year got sick, and when his alternate backed out at the last minute, and when it got to be a month into the fall term with no replacement in sight, the State Department called Alex in a panic. They wanted to know if he couldn't find someone at Dartmouth who would go. It would have to be a man who could (a) lecture on American literature and (b) leave immediately.

Normally teachers never do anything immediately. (Fulbright professors, for example, are appointed a full year before they actually go; and new faculty at Dartmouth are usually hired in January, start teaching in September.) But I happened to be on sabbatical this past year, free to come and go as I pleased. I also teach American literature.

So when Alex called the chairman of the English department, the chairman phoned me. Two days later the Polish Ministry of Education was deciding whether I was acceptable. Two days after that I was on my way. Among other things, I had gotten a U. S. passport in 37 minutes — no record, maybe, but evidence that even bureaucracy can move fast on occasion.

What I knew as I flew into Warsaw last November can be put in about four sentences. I knew I was going to be emergency temporary Fulbright professor at Uniwersytet Warszawski for six weeks. I knew that I would be teaching both graduate students and undergraduates. I knew that Poland was a communist but also Catholic country, slavic but also western, with the misfortune to be wedged between Russia and Germany. I knew that the Russian jet — belonging to the Polish airline LOT — on which I was flying was incredibly noisy. Everything else I had still to learn.

Two more days, and I had met my first class. Except that of the nine students in it. six were girls, it was not so different from a Dartmouth class. The same liveliness, the same sharp intelligence, even a few of the same jokes. I had also met a dozen Polish teachers, most of them rather more formal than American academics, and I had had a letter from His Magnificence the Rector of the University. (It's the one pre-war title surviving in communist Poland.) I was beginning to learn my way around.

I was still just beginning to learn when I left six weeks later. Learning is slow in a country where you ask about the city of Lodz and find it's really called Wootsh. But I did get some sense of what life is like in a communist university.

In some ways that life is very much less free than it is at Dartmouth or any other American college. For example, the chairman of my department at Warsaw often complained to me that the students had too many hours of class. Freshmen and sophomores, she lamented, are required to be in class something over forty hours a week. Too much for them to absorb, too much for the faculty to teach.

Now I had made up my mind before going to Poland not to offer a lot of suggestions when I got there. The most annoying friend I ever had at Dartmouth was a man who came from teaching at Yale and who never let a week pass without objecting to the way Dartmouth did something or other and explaining how much better whatever it was would have been handled at Yale. Even so, the third time that Professor Dobrzycka lamented the forty hours a week in class, I heard myself saying, well, if the students don't like it and the faculty doesn't either, why not reduce the number of hours.

Professor Dobryzcka smiled a weary smile. "It's not so easy as that," she said. And she explained that the curriculum for all Polish universities is set by a committee in the Ministry of Education, and the committee only even meets once every five years. It was my first encounter with a real, live Five-Year Plan, and I'd just as soon it was the last.

But in other ways I found Warsaw a truly free university. Certainly in my own work I did. My job was to teach three courses: a lecture course for all 40 fourth-year students in the Instytut Filologii Angielskiej or English Institute, another lecture course for the fifth-year majors in American literature, all nine of them, and a weekly seminar for the same nine. (These were my "graduate students," only in Poland they aren't. There is no B.A. degree in Poland; everyone goes to college five years and gets an M.A. at the end.)

In the fourth-year course I was supposed to be surveying American literature, and there was a syllabus to follow, just as there is at Dartmouth. All this meant was that I was committed to lecturing on Jack London and Robert Frost and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and was not supposed to bring in Jack Kerouac or Robert Service. No commissar came to class to check up on what I said. No student who stayed after class seemed to have the slightest hesitation in criticizing either Polish or American ideas.

In the fifth-year lectures there was not even a syllabus. My orders were to design the course myself. At first I simply lectured on some of the best new American novels — a couple of Kurt Vonnegut's, Ken Kesey's One Flew Overthe Cuckoo's Nest, and so on. I had meant to include Salinger's Franny andZooey, but dropped it when I found that everything Salinger has written has been translated into Polish, and the students knew him inside out already.

About halfway through my six weeks, though, I had got on good enough terms with these M.A. candidates that I invited them to share the design of the last few classes with me. The result was that we immediately dropped the lecture form. We also quit meeting in Room 1203 of the Palace of Culture — a Gothic-looking skyscraper in the center of Warsaw, known to Poles as the Wedding Cake. It was a present from Russia in the fifties. Instead we started going to a cafe, where we would get a private room, order glasses of tea, and sit around discussing both Polish and American literature and politics.

We were all frank. I heard plenty about the censorship of Polish literature, and even about the total suppression of certain radical writers. No one has suppressed Eldridge Cleaver or Abbie Hoffman, and both the students and I agreed that Americans have much more liberty of expression. We also agreed it wasn't total. One of the nine was doing his M.A. thesis on Norman Mailer. Poland is short on foreign currency, and American books are hard to come by. He had hoped to get copies in the United States Information Service library at our embassy—which is, of course, designed for Poles to use. None there, he said. This seemed improbable for so distinguished a writer as Mailer, so I checked. The library turned out to be in the curious position of having three books about Mailer—serious critical works - but not a single book by him, not even The Naked and the Dead. Apparently the State Department doesn't approve of Mailer. (Which may be fair enough. I gather he doesn't approve of it.)

Once or twice we talked about social classes. Poland had four of these up until World War II: peasants, workers, intelligentsia, and the aristocracy. It still has the first three, and Poles think a good deal in class terms. In fact, when I registered with the Warsaw police, practically the first question they asked me was what class I belonged to. No American is going to admit belonging to any class, and I answered, half grinning, that we are a classless society. The middle-aged woman who was questioning me (in Polish—I had a university colleague along to translate) looked perfectly stone-faced, and repeated the question. Since I have a farm in Vermont, my temptation was to say peasant. This horrified my colleague, who quickly said that anyone who has been to college, much less teaches there, is by definition intelligentsia, and so I duly registered as that.

Poles do not ask this question just out of curiosity. They have a class system, but they are trying to break it down. Most strikingly, teenagers who are classed worker and peasant get about a 20 per cent bonus on their college entrance exams—rather the way "disadvantaged" students do at most American colleges now. In both cases the motive seems to me idealistic, and results more good than bad.

One thing I never met at the university was a party member. Some of the students had belonged to communist youth groups when they were in their early teens, but this seemed to mean no more to them than previous membership in the Boy Scouts does to a Dartmouth undergraduate. I did hear about another Polish university where the head of the English department is an active party member; in fact there was a certain jealousy of him on the part of the faculty at Warsaw, because he could more easily get books from the States than they could, had a subscription to Time, and so on. But no one at Warsaw was joining the party in order to get Time.

In fact, my final impression is that Poles are intensely interested in Poland, but only moderately interested in earn ing the gospel of communism, or any other gospel, to other countries occasionally had a somewhat tepid discussion of Vietnam with a group of students. At first I was surprised the conversation was so mild, since I had learned the first week that the Polish government officially supports North Vietnam. (There were photographs up in two or three places around Warsaw showing U. S. soldiers using napalm on civilians, and so on.) But what the students turned out to feel was that while we had no business in Vietnam, they didn't either, and why not talk about something nearer home. This might be the skiing at Zakopane, or the differences between England and America—more than half my students had visited England at one time or another—or the question of what industrial pollution is doing to Krakow. But in the end it usually came back to Polish freedom. Poles have often lacked it, and not least academic freedom.

I learned, for example, that all classes at Warsaw University were given in Russian until 1916—a fact which both shocked me and set me to wondering uneasily what language they were given in at the University of Puerto Rico then. I learned that no classes at all were held at Warsaw between 1939 and 1945; the Germans closed the university, as they did all Polish universities and all Polish high schools, and even junior high schools, on the grounds that Poles are not fit to be educated. In fact, one of the most upsetting stories I ever heard was told me by a colleague whose father was teaching at the great medieval university of Krakow in 1939. That university was shut tight during the German invasion. By November things had settled down, and the rector asked the German commanding general in Krakow if it would now be appropriate to start the school year. He said "why don't you call a faculty meeting, and we'll talk about it The rector did, whereupon German soldiers arrested the entire faculty and sent them to concentration camps.

Poles don't forget that. They don't forget Russian concentration camps. And though it means so much less to them, they don't even forget the ones we have in Vietnam under the name of relocation centers. My students were ready to argue that as long as there are any such camps there cannot be truly free education. But to my mind it is astonishing and very heartening to see how much freedom there is in communist Poland right now.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMan and His Environment

June 1971 By ALVIN O. CONVERSE -

Feature

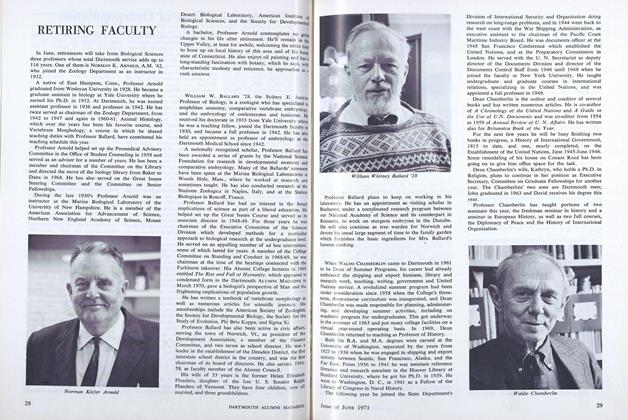

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1971 By B.B. -

Feature

FeatureWhat Price Clean Air?

June 1971 By Robert B. Graham '40 -

Feature

FeatureThe Marxist View of Overpopulation

June 1971 By Charles W. Collier '71 -

Article

ArticleA Second Life Through Heart Surgery

June 1971 By Daniel L. Dyer '39 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1971 By JOHN H. MARSHALL '71

NOEL PERRIN

-

Books

BooksTHE CHRISTENING PARTY.

February 1961 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleMinor Issues

MAY 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleDartmouth, Dartmouth, Doing Right

OCTOBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleO Wisest Vox, All-Knowing Vox, Silent Vox

DECEMBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleLooking for Frost

DECEMBER 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

MARCH 1999 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

FEATURE

FEATUREWisdom of the Sages

MARCH | APRIL 2017 -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

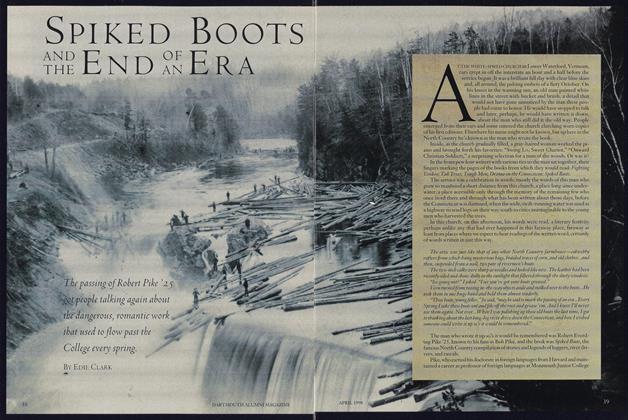

FeatureSpiked Boots and the End of an Era

APRIL 1998 By Edie Clark -

Feature

Feature"Hi. My Name's John. I'm a Zero."

NOVEMBER 1997 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Feature

FeatureFinancing Higher Education

MARCH 1972 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureBusiness as a Social Service

October 1956 By THE HON. RALPH E. FLANDERS, LL.D. '51, U.S. SENATOR FROM VERMONT