THE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

There is a quiet crisis at Dartmouth today. Obscured by the excitement over coeducation and year-round operation is the fact that fraternities are in trouble. Since 1969 total membership in the fraternity system has dropped 25% from 1431 to 1070. The percentage of upperclassmen associated with a fraternity has fallen from 64% to 48%—it is below 50% for the first time in half a century. Two houses, D.K.E. and Phoenix (Phi Gam), are gone; and several others are tottering on the brink.

The membership crisis has illuminated other problems of fraternities, most of which stem from the void in the supervision of house management left by the demise of the Inter-Fraternity Council and the relinquishing of national affiliation by many houses. The search for solutions is complicated by the multiplicity and' complexity of the causes, but a serious effort is being made. The purpose of this article is to explore the nature and causes of the Dartmouth fraternity crisis, and to point out the probable avenues of solution.

At the heart of the fraternity crisis is the drop in membership. Even a degree of mismanagement can be tolerated when membership generates sufficient revenue to pay the bills. The decline in membership occurred suddenly over the past three years. Part of the drop can be attributed to a decrease in the size of the pledge class from a 1960-69 average of 450 to 346 in 1971; and part is due to an increase in the number of upperclassmen going inactive. Generally, the houses hurt most by the membership decline have been those located off fraternity row. D.K.E. has been sold to Howe Library; Phoenix (Phi Gam) has asked the College to take over its physical plant; Gamma Delt, Phi Psi, Zeta Psi, and Foley House have fewer than 25 members; and Pi Lamb, Phi Tau, Theta Delt, and Harold Parmington Foundation (T.E.P.) had fewer than 12 pledges in 1971.

The nature of the decline can be attributed to Dartmouth's "open" fraternity system which encourages "house hopping" on the weekends. The causes of the total decline in membership are not so apparent.

The change in student attitudes towards fraternities and institutions in general is certainly one cause. Dartmouth students today are more independent and self-reliant than their predecessors, and they seem to have little commitment to institutions in general. Fraternities, having a legacy of encouraging social conformity (e.g. through hazing and pledge training to make the pledge part of the group), are not particularly appealing. There is a pervading egalitarianism within the Dartmouth student body today, and fraternities with their system of selective rush smack of elitism. Fraternities have changed with the times—they no longer practice hazing and pledge training is virtually gone. But the legacy of the past still colors students' conceptions of fraternities.

With the weakened belief in the ethical desirability of fraternities is coupled the increased mobility of the Dartmouth student body. The large number of automobiles on campus, the easy access to socially more attractive areas, and the "road tripping" ethos of much of the student body have lessened the dependence on social centers in Hanover. Then too, social life today is centered around smaller, more intimate groups of friends than before—and dorms since the abolition of parietals in 1969 provide all the necessary facilities.

To be frank, the increased enrollment of disadvantaged and minority students is a contributing factor in the membership decline. Fraternities today certainly practice no discrimination in pledging—in fact, a special effort is made to persuade minority groups to join fraternities. But for economic and other good reasons too difficult to enumerate here these groups have chosen to bond fraternally with "their own." Thus the size of the prospective pledge class is cut 10-15%.

The root cause of the membership fall, however, is simply money. Dartmouth's tuition, room, and board have risen from $2250 in 1960 to $4495 in 1972, with most of the increase coming since 1965. With the cost of a college education now so high, the luxury of fraternity membership costing between $250 and $300 a year is not easily afforded. With the rising economic pressure has come increased exploitation of the openness of the fraternity system. Many independents believe the advantages of fraternity membership such as bands, parties, and beer can be enjoyed without paying the price—and until this year fraternities were hesitant to exclude independents from fraternity functions.

The decline in fraternity membership and the financial strain it has imposed on the houses has brought to light another serious problem of the present fraternity system—the problem of management. With only a few exceptions, fraternity corporations and faculty advisers have not exercised the rigorous supervision of the management of houses that the Inter-Fraternity Council and the national chapters formerly required. Thus houses are left in the hands of undergraduates quite inexperienced in overseeing $50,000 to $100,00 worth of plant and equipment with an annual budget of approximately $15,000. Errors of management could be absorbed and chalked up to learning experience when houses were at full membership—but with falling membership and rising costs, good management can now mean the difference between success .and failure for those houses on the margin. Evidence of poor management and rising costs is not hard to find in the deteriorated facilities of many houses.

The change in student attitudes, the change in the kind of student at Dartmouth, the economic pinch, and the problems of management have converged to precipitate the present crisis in fraternities at Dartmouth. The future presents two more challenges—coeducation and year-round operation. It is almost impossible to predict the impact of coeducation on fraternities. Whether it will increase or decrease the demand for social facilities is a matter for speculation. One thing is clear, however—coed social societies are well within the realm of possibility.

Year-round operation presents a different problem. With the increased shuffling in and out of Hanover of the student body, the cohesiveness of fraternity life will be severely weakened. Still, fraternities may be able to provide the only stable basis for social life on campus. The College is not unaware of the strain on social life imposed by year-round operation, and it is exploring the possibility of residential colleges — complexes of living units, faculty offices, and recreation facilities in which a student would be assured residence whenever he is in Hanover. While stabilizing social relationships, residential colleges with improved quality of life would inevitably offer competition to fraternities. The present fraternity system has one of its main justifications in the rather austere dorm life which requires students to get out and seek other social outlets. Any improvement in dorm life will only make it less attractive to spend the extra money for fraternity membership.

The nature and complexity of the causes of the fraternity crisis coupled with the new challenges of the Dartmouth Plan make solutions to fraternity problems very difficult. Responsibility for devising solutions has been placed in two bodies—the Inter- Fraternity Council and the Fraternity Governing Board. In the late 1960's with the weakening of fraternity spirit and the diversification of life styles in fraternities came a languishing of the effectiveness of the I.F.C. The enforcement mechanisms lost legitimacy as the system grew weaker and the I.F.C. became little more than a figurehead. But by the spring of 1971 the problems besetting fraternities had become too large to ignore any longer, and in their urgency was found a means to unify houses behind the I.F.C. It was last spring too when the College began to recognize the depth of the problems facing fraternities and the repercussions of the failure of the fraternity system on life at Dartmouth. The College suggested the establishment of a Fraternity Governing Board which would serve as a forum to suggest and help implement policies to strengthen fraternities. Out of a meeting of fraternity corporation officers last spring came a proposal for a board consisting of the Dean of the College, three corporation officers, three faculty advisers, and four members of the I.F.C. The Governing Board began to operate in November 1971. In general, the I.F.C. has concerned itself primarily with means of increasing membership while the Governing Board has concerned itself with problems of management.

The first priority of course is enhancing membership. The first action of the I.F.C. was to open houses to freshmen on a limited basis for spring term—during the week and by invitation on the weekends. The hope was that by exposing freshmen to fraternity life, their preconceptions and prejudices about fraternities could be broken down. But last fall there was no significant impact in rush. As a stopgap measure, the I.F.C. took action against independents by closing all fraternity parties with bands. The I.F.C. then began serious consideration of the possibility of holding rush for freshmen in the spring of 1972.

There are many good reasons why freshman rush would benefit not only fraternities but freshmen and the College. Freshmen are more mature and more capable of handling the pressures responsibilities, and distractions of college than were their predecessors of 1926 when the rule excluding freshmen from fraternity membership was imposed. That freshmen need and desire fraternity membership is indicated by the difficulty of enforcing the rule prohibiting any freshman from entering a house except on business. With year-round operation, the spring term of freshman year will be the last time an entire class is on campus at one time, making rush at any later time difficult. Rush during the school year increases the opportunity for publicizing rush and means men do not have to cut their summer short to return to Hanover for rush before school in the fall. A proposal for freshman rush was drawn up, approved by the Dean of Freshmen, passed by the Faculty Committee on the Freshman Class, and sent to the President.

Plans are now under way for a rush of freshmen in April. The hope of course is that there will be a significant rise in the number of men pledging. However, if the membership crisis cannot be resolved—and indeed there are many of the causes of the crisis which simply cannot be reached—then not only management but the future of fraternities becomes a serious problem. The Fraternity Governing Board is in the process of drawing up a master plan for the fraternity system to be presented to the College and the houses for consideration. Given present membership levels, the Governing Board has three alternatives. First, the Board could propose essentially to do nothing and let fraternities try to work their own way out of their problems under the present system. The effect of such a policy would probably be a decrease in the number of houses to about 15 within two years, with little assurance that further deterioration in the system would not occur. Given the present belief by many in the continued desirability of fraternities at Dartmouth, this alternative is likely to be rejected.

The Governing Board secondly could propose a very drastic restructuring of jhe present system, perhaps along the lines of the Amherst system. At Amherst the college has taken over management of fraternities and subsides them heavily. The restructuring would probably call for a reduction in the number of houses to about 15 with increased membership limits of 85. however, the lack of available College funds, the College's policy not to use general funds on a basis that favors one group of students over others, and the lack of authority in the Governing Board to order a house out of existence all militate against such a solution. One proposal, if funds were available, is to grant every student a sum of money (perhaps $200/year) to strengthen his chosen living unit—whether dorm, residential college or fraternity. Such a massive restructuring is not likely to be proposed at this time.

A third alternative lying somewhere between the first two is to make several important adjustments in the present system to increase its efficiency, and then allow the market to determine how the system expands or contracts. Some of the adjustments would involve increased use of College facilities to make management of houses more effective. The College already allows purchasing of maintenance supplies through its warehouse, and has just granted fraternities the right to place bad debts on college bills for collection. One proposal under study is the hiring of a business manager by the College to supervise the management of fraternities. ties. Replacement of the present "ride" system by a system which allows a house to make available loans administered by the College financial aid office is receiving consideration. Much thought is being given to how fraternities can expand the number of functions they perform, e.g. expansion of eating and cooking facilities, to make fraternity membership more attractive. Another suggestion is to increase the membership limit from the present 65 to 85. The effect of such an increase would probably be to hasten the failure of the smaller houses. This idea has some merit in that under year-round operation only two-thirds of the membership of a house will be on campus at one time. In effect, the restructuring involved in the second alternative would occur naturally. The folding of houses would probably occur through merger rather than outright failure—and the pooling of assets would increase the financial stability of the survivor.

Regardless of the alternative chosen by the Governing Board, the houses, and the College, one thing is clear. Unless there is a significant increase in fraternity membership in the next two years, several more failures are inevitable. Despite valiant efforts by houses with fewer than 25 members to remain in operation, it will be almost impossible for them to survive. As more members are required to live in the houses, fewer members are left in the dorms to provide contacts with prospective rushees—and rush is hurt. With the fall in revenues, small houses pay their bills but are unable to finance the capital improvements which will preserve the house's longevity. The present level of membership can support only 16 or 17 houses.

Fraternities have been for over 100 years an integral part of the Dartmouth experience. They are threatened today by increasing economic pressure, a change in the character of the Dartmouth student, and by a change in Dartmouth itself. In the past it has been largely the responsibility of fraternities to develop the social as opposed to the academic side of the Dartmouth man. Their premise has been that a socially adjusted person will be happier and more successful in coping with life's problems than one who is socially insecure. Their success is indicated not only by the better academic performance by fraternity members than by non-fraternity members, but also by the success beyond Dartmouth of their alumni.

It may not be possible to save all 22 remaining fraternities. But the failure of even one fraternity is indicative of the emergence of a different Dartmouth than that of the past. It is indicative of the gradual disappearance of some of the traditions and institutions that made the Dartmouth experience unique. What is to come may be judged better than what has been, but it will not emerge without a great feeling of loss for what is gone.

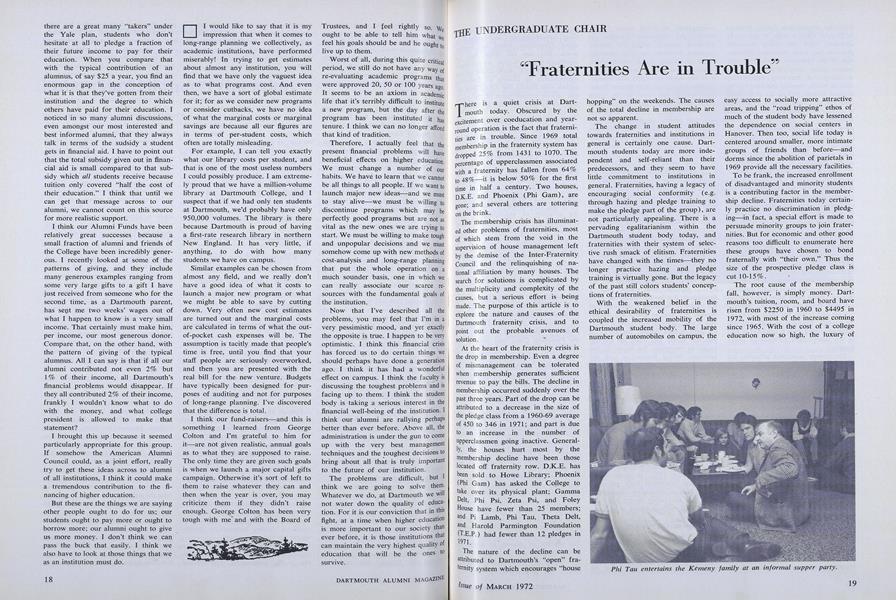

Phi Tau entertains the Kemeny family at an informal supper party.

Margee Russell of Peoria, Ill., a Colby Junior College freshman, was chosen1972 Dartmouth Winter Carnival Queen. She poses here with Dean Carroll Brewster (left) and her date, Bill Farnum '73, a member of Kappa Kappa Kappa.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFinancing Higher Education

March 1972 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeaturePilobolus: Energetic Dance-Theater

March 1972 By ANDREW W. CASSEL '72 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Institute Plans First Session

March 1972 By M.R. -

Article

ArticleFaculty

March 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1972 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

March 1972 By GORDON A. THOMAS, CARLL K. TRACY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSTEINER: by himself

March 1979 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

FeatureA Course of Reading for Dartmouth Men

December 1955 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Testa Hit

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

APRIL 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86 -

Feature

FeaturePublic Policy: The Ordeal of Choices

JANUARY 1971 By William D. Carey