"I happen to be very optimistic. I think thisfinancial crisis has forced us to do certain thingswe should perhaps have done a generation ago."

In trying to choose a topic for my remarks today I had a dilemma. This conference has certain themes and I had to decide whether to pick one of them and run the risk of saying what you have already heard three times before, or to choose a totally different topic and run the danger that at the moment your minds would be concentrating on something entirely different. I decided to fall into the former trap and pick up one of your themes. I would like to. make my remarks on the problem of financing higher education.

I think it is worth taking a look at the causes that have brought about what can only be described as a crisis in most academic institutions. I know that a great deal has been written on this. We all have our favorite analysis of these problems, but sometimes people have looked too narrowly at what has happened in the last three years and do not recognize that some of the causes go back as far as twenty years. The causes were there long ago; it is only that the cumulative effect wasn't clear until the present date.

The first and most important change, of course, is the fact that twenty years ago institutions of higher education were heavily subsidized. They were subsidized not in terms of endowments, but by the fact that the faculty and administration of the institutions were willing to work for those institutions for practically no pay at all. If you look at the causes of the significant changes in the financing of higher education, you must recognize that one of the most important ones has been the paying—in recent years—of a decent wage to faculty and administrative officers.

To give you an example, I was hired by Dartmouth College less than twenty years ago as a full professor at a salary of $6,000. I think it is worth mentioning that figure because many of us have forgotten where we were less than twenty years ago. I cannot complain about my salary at all, not just as President, but even as a full professor. Dartmouth has always treated me very well, but Dartmouth, like all other institutions, had to come a very, very long way until salaries of professional educators were comparable to those of other professions in the country.

A second major factor has been the effect of the knowledge explosion. I took a look at the increase in the size of the faculty in the decade of the 60's, a period when at Dartmouth the increase in the student body was negligible. The increase in the size of the faculty in the past decade is totally out of proportion to the increase in the number of students, and it came about—at least that is my analysis—as a result of the vastly greater complexity of human knowledge and the need to cover a great many subjects that had never appeared in academic curricula before.

The dilemma for the liberal arts institution is that you are trying to protect that which is old and has been treasured through the ages, and yet, you must also try to be up to date, and cover the needs of the next generation. A necessary by-product of this has been a vastly richer curriculum and one that has a much larger number of faculty members per students.

The third factor—often mentioned—has been the cutback of federal aid. Now let me restate that differently. I think the truly important factor has been the vast increase of federal aid in the previous decade, which led many institutions to a rather artificial inflation of their faculties and to new programs based on funds that history has proved, in the long run, not reliable. Thus, we have the combination of a very rapid build-up over a period of a decade and then a subsequent rapid cutback which has made this a significant factor in the financial crisis.

The fourth factor is clearly inflation. All of our educational institutions are best off in a fairly stable monetary situation because it is very difficult for them to react to inflation as rapidly as certain service and manufacturing industries where the cost can be passed on immediately to the customer. Our endowments have difficulty increasing at a sufficient rate to keep up with inflation. Levels of giving do not rise as rapidly as inflation. The other source of funds is tuition and I know that you had a great session discussing the problems of the rapidly increasing tuition that faces all educational institutions.

The fifth and final factor I want to mention is the coming of the equal opportunity programs. I personally believe these were necessary and overdue. Nevertheless one must recognize that at least for those institutions that have relied on tuition revenue as the single major source for financing higher education, and have always been generous in providing financial aid when necessary, the admission of a much larger number of students who can pay only a very small fraction of the cost of education is a fifth and very important factor in bringing about today's financial crisis.

When I became President of Dartmouth I knew nothing at all about the financing of the institution. I asked my budget officer to make a detailed study of what had happened to the budget of the College in the previous 17 years. There's a fairly sharp point in the early 1950's marking the onset of major changes at Dartmouth— about 17 years before I became President. The changes in faculty salaries, the big increases in faculty, and many other significant changes all started at roughly the same time. I found out to my absolute horror that over that 17-year period the budget of the College had been increasing at an annual compounded rate of between 10 and 11% a year- (Incidentally, it is interesting that in a pre-study guessing contest all of us turned out to be wrong about what the rate would be—the matter had never been looked at in just this way.) During this 17-year period the number of students had increased by a compounded rate of 1% per year. So I think I have a strong case for saying that it is the other factors that really brought about the financial crisis. It is perfectly clear to me that, given today's financial conditions, increases at the rate of 10% or more per year are totally unrealistic, and that we must learn how to control our institutions without getting into this absolutely horrendous period of fiscal expansion.

We are all secretly hoping that the Federal Government will come to the rescue. I do believe that on a small scale they actually will, but as you know, there are many delays and even if the best of the bills now before Congress should pass (I'm trying very hard not to take a position on which is the best of the bills) the money available to most of our institutions will be an amount that will be very nice to have but that will do very little to solve our long-range problems. Therefore, I do not believe that the Federal Government is, within the next decade, going to solve our problems for us.

Let me now turn to the specific question of the financing of undergraduate education. Graduate education is diverse and quite complicated. For example, taking two of our professional schools, the situation is so different in the Medical School, which relies primarily on federal aid, and in our Amos Tuck School of Business Administration, which relies primarily on support from industry and tuition from students, that any general discussion would be difficult. I think it is simpler to concentrate on the problem of undergraduate education, a problem all of us have encountered.

One very often says that tuition covers only half the cost of undergraduate education. As a matter of fact, I have heard this said so often that it occurred to me to check to see whether there was any truth in it. So, I had my budget officer do a very careful estimate the cost of education of a typical Undergraduate, and the fraction of it covered by tuition. He said that depending on how you calculate it something between 49 and 52% of the cost is covered by undergraduate tuition. In other words, tuition covers half the cost of undergraduate education.

The next statement to be made is that this statement is obviously false. You see, we all play games with our budgets. What we really should say is that half the cost of undergraduate education would be paid by undergraduate tuition if all our students really paid the tuition that we announce. But roughly half of our students don't pay that tuition because we give part of it back to them in the form of financial aid. Due to this lovely, pretend bookkeeping we really believe that all this tuition is paid to us even though a substantial part of it—in the case of Dartmouth College roughly one-third of it—is given back to students as financial aid. So we fool ourselves into believing numbers like "half the cost of education." When you take into account financial aid, it is more like one-third of the cost of undergraduate education that is paid in tuition (in terms of real money) and this fraction is in danger of getting smaller every year, due to several different forces that are acting upon it.

First of all, it's becoming more and more difficult to increase tuition as fast as costs are going up. Secondly, those students already on financial aid are in a position where they and their parents are contributing all that they can, and therefore every time we increase tuition all the incremental cost of education must be given to them in the form of financial aid, unless some other solution is arrived at. Finally, every time we increase tuition a larger percentage of students need financial aid. A combination of all of these factors makes the spiral of tuition increases a suicide course for higher education.

This is, of course, why we all have looked with such tremendous interest at the highly imaginative experimental plans that have been launched by Yale and Duke Universities. At Dartmouth we ourselves will be engaged, starting a week from today, in an intensive one-year study of the whole question of the financing of undergraduate education as members of a coalition consisting of Dartmouth, Harvard, Princeton, Brown, MIT, Wellesley, Mt. Holyoke, Amherst, and Wesleyan. Thanks to a grant from the Sloan Foundation, we hope to have an intensive study on just exactly what it costs each of our institutions to educate an undergraduate; what it is realistic to expect parents to contribute; what it is realistic to expect students to earn while they are in college; and what other sources there might be for closing the gap between tuition and costs, including, of course, some means of borrowing while students are in college, to be repaid out of earnings later on. It's our very great hope that if this study is successful we may come up with a proposition which certainly should be of interest to other educational institutions.

While these studies are limited to the largest number of institutions we felt would have any chance of getting together on ideas, We certainly hope to share any recommendations that come out of this with all other institutions. We hope very much that this might become the nucleus for major regional efforts to have similar plans for the financing of undergraduate education—perhaps a regional or national loan plan or whatever else may come out of our study—plans that would be open to all institutions that might wish to participate.

A second major factor, and one in which this group has a particular interest, is the contribution made to the institution by its alumni. It's very pleasant to bring up that topic when you are President of Dartmouth College because so very often our alumni turn out to have the highest percentage of participation in the nation. That is a very wonderful testimonial to the way your alumni feel about your institution. And yet, there is a fundamental problem that all our institutions share—we have failed to raise the sights of our alumni as to what constitutes a reasonable contribution to their alma mater.

Under the Yale plan, for example, it will be very common for students graduating from Yale University four years from now to pay 2% or 3% of their income, for most of their productive lives, to Yale University. Apparently there are a great many "takers" under the Yale plan, students who don't hesitate at all to pledge a fraction of their future income to pay for their education. When you compare that with the typical contribution of an alumnus, of say $25 a year, you find an enormous gap in the conception of what it is that they've gotten from their institution and the degree to which others have paid for their education. I noticed in so many alumni discussions, even amongst our most interested and best informed alumni, that they always talk in terms of the sudsidy a student gets in financial aid. I have to point out that the total subsidy given out in financial aid is small compared to that subsidy which all students receive because tuition only covered "half the cost of their education." I think that until we can get that message across to our alumni, we cannot count on this source for more realistic support.

I think our Alumni Funds have been relatively great successes because a small fraction of alumni and friends of the College have been incredibly generous. I recently looked at some of the patterns of giving, and they include many generous examples ranging from some very large gifts to a gift I have just received from someone who for the second time, as a Dartmouth parent, has sept me two weeks' wages out of what I happen to know is a very small income. That certainly must make him, per income, our most generous donor. Compare that, on the other hand, with the pattern of giving of the typical alumnus. All I can say is that if all our alumni contributed not even 2% but 1% of their income, all Dartmouth's financial problems would disappear. If they all contributed 2% of their income, frankly I wouldn't know what to do with the money, and what college president is allowed to make that statement?

I brought this up because it seemed particularly appropriate for this group. If somehow the American Alumni Council could, as a joint effort, really try to get these ideas across to alumni of all institutions, I think it could make a tremendous contribution to the financing of higher education.

But these are the things we are saying other people ought to do for us; our students ought to pay more or ought to borrow more; our alumni ought to give us more money. I don't think we can pass the buck that easily. I think we also have to look at those things that we as an institution must do.

I would like to say that it is my impression that when it comes to long-range planning we collectively, as academic institutions, have performed miserably! In trying to get estimates about almost any institution, you will find that we have only the vaguest idea as to what programs cost. And even then, we have a sort of global estimate for it; for as we consider new programs or consider cutbacks, we have no idea of what the marginal costs or marginal savings are because all our figures are in terms of per-student costs, which often are totally misleading.

For example, I can tell you exactly what our library costs per student, and that is one of the most useless numbers I could possibly produce. I am extremely proud that we have a million-volume library at Dartmouth College, and I suspect that if we had only ten students at Dartmouth, we'd probably have only 950,000 volumes. The library is there because Dartmouth is proud of having a first-rate research library in northern New England. It has very little, if anything, to do with how many students we have on campus.

Similar examples can be chosen from almost any field, and we really don't have a good idea of what it costs to launch a major new program or what we might be able to save by cutting down. Very often new cost estimates are turned out and the marginal costs are calculated in terms of what the out-of-pocket cash expenses will be. The assumption is tacitly made that people's time is free, until you find that your staff people are seriously overworked, and then you are presented with the real bill for the new venture. Budgets have typically been designed for purposes of auditing and not for purposes of long-range planning. I've discovered that the difference is total.

I think our fund-raisers—and this is something I learned from George Colton and I'm grateful to him for it—are not given realistic, annual goals as to what they are supposed to raise. The only time they are given such goals is when we launch a major capital gifts campaign. Otherwise it's sort of left to them to raise whatever they can and then when the year is over, you may criticize them if they didn't raise enough. George Colton has been very tough with me and with the Board of Trustees, and I feel rightly so. We ought to be able to tell him what we feel his goals should be and he ought to live up to them.

Worst of all, during this quite critical period, we still do not have any way of re-evaluating academic programs that were approved 20, 50 or 100 years ago It seems to be an axiom in academic life that it's terribly difficult to institute a new program, but the day after the program has been instituted it has tenure. I think we can no longer afford that kind of tradition.

Therefore, I actually feel that the present financial problems will have beneficial effects on higher education We must change a number of our habits. We have to learn that we cannot be all things to all people. If we want to launch major new ideas—and we must to stay alive—we must be willing to discontinue programs which may be perfectly good programs but are not as vital as the new ones we are trying to start. We must be willing to make tough and unpopular decisions and we must somehow come up with new methods of cost-analysis and long-range planning that put the whole operation on a much sounder basis, one in which we can really associate our scarce resources with the fundamental goals of the institution.

Now that I've described all the problems, you may feel that I'm in a very pessimistic mood, and yet exactly the opposite is true. I happen to be very optimistic. I think this financial crisis has forced us to do certain things we should perhaps have done a generation ago. I think it has had a wonderful effect on campus. I think the faculty is discussing the toughest problems and is facing up to them. I think the student body is taking a serious interest in the financial well-being of the institution. I think our alumni are rallying perhaps better than ever before. Above all, the administration is under the gun to come up with the very best management techniques and the toughest decisions to bring about all that is truly important to the future of our institution.

The problems are difficult, but I think we are going to solve them. Whatever we do, at Dartmouth we will not water down the quality of education. For it is our conviction that in this fight, at a time when higher education is more important to our society than ever before, it is those institutions that can maintain the very highest quality of education that will be the ones to survive.

President Kemeny gave the principaladdress at the New England DistrictConference of the American AlumniCouncil at Manchester, N. H., onJanuary 25, 1972. The following is themajor portion of his remarks on thatoccasion.

"I do not believe that theFederal Government is,Federal the next decade,going to solve our problems for us."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Fraternities Are in Trouble"

March 1972 By DAVID WRIGHT '72 -

Feature

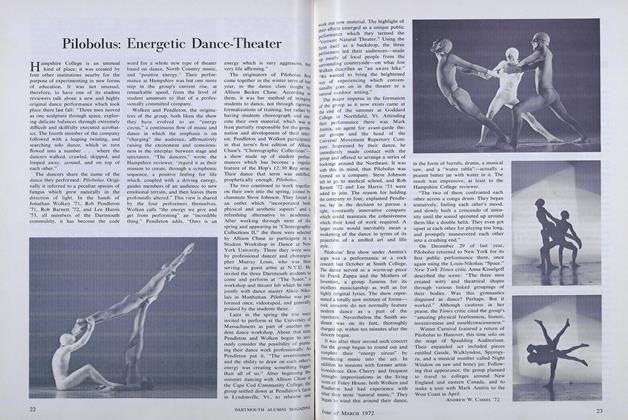

FeaturePilobolus: Energetic Dance-Theater

March 1972 By ANDREW W. CASSEL '72 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Institute Plans First Session

March 1972 By M.R. -

Article

ArticleFaculty

March 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

March 1972 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

March 1972 By GORDON A. THOMAS, CARLL K. TRACY

John G. Kemeny

-

Article

ArticleStatement by the Board of Trustees

February 1977 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticlePresident Kemeny to President Nixon...

NOVEMBER 1970 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleThe road less traveled

DECEMBER 1971 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1972

JULY 1972 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to '73

JULY 1973 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThe Bakke Case

OCT. 1977 By John G. Kemeny

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe President's Valedictory Address

June • 1985 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryYoung P. Dawkins III '72

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Rise of Research

FEBRUARY 1989 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

MAY • 1988 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureTHE EDUCATION LADDER

MARCH 1965 By PROF. BURTON E. MARTIN '33