By Arthur M. Wilson (DanielWebster Professor and Professor of Biography and of Government, Emeritus).New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.917 pp. Illustrated. $25.

It's a big, fat baby (917 pages), like Rabelais' Gargantua, likewise dimpled, smiling, very pleasant. It took a whole career at Dartmouth — almost 40 years—to create, in the scanty leisure left by courses in biography, history, government, chairmanship of departments and committees, direction of the Great Issues course, editorship of the Journal of Modern History, etc. Professor Wilson arrived at Dartmouth in 1933 and we soon became friends: we had a love in common, the eighteenth century. I was a little useful in clearing up a few nuances of French style. He was then completing his French foreign policy during the administration of Cardinal Fleury, 1726-1743. Harvard University Press published it in 1936. Because not much had been written in English beside the two volumes of John Morley, Diderot and the Encyclopaedists, 1921, also because he sensed that Diderot, then a poor fourth in the French race for prominence in the 18th century, would soon become the front runner on account of his modernity, Professor Wilson started on his long, painstaking research, with the help of Mrs. Wilson. He became the Boswell of this Johnson. He identified himself with his author, shared in his encyclopedic knowledge, liberalism, intellectual honesty, warmth of heart; he preserved, however, all his scientific, objective judgment to point out the foibles of the atheistic, talkative, effervescent, impetuous, sometimes disorganized and naïve Diderot. At the same time he painted an accurate, detailed picture of pre-Revolutionary times, traced and analyzed the main trends which affected Diderot's works. The cutler's son from Langres, a brilliant student of the Jesuits of Paris, preferred bohemianism to a law career. With an omnivorous appetite for learning, he acquired the knowledge that fitted him to edit the Encyclopédic. He was bold enough to give it an anti-Establishment turn that landed him in jail, charming enough to woo and win influential friends, especially ladies, and meld them into a team of progressive scholars and philosophers who helped write and publish twenty-five volumes over a period of twenty years. The license was revoked in 1759; this blow by the royal censure marks the end of Professor Wilson's first volume, The Testing Years (1713-1759) (1956, Oxford University Press), awarded the Modern Language and American Historical Associations' annual prizes.

The same sentiment de présence and minute search for truth pervades the second part of Professor Wilson's Diderot. It is entitled The Appeal to Posterity (1759-1784) and rightly so. Denis continues his uphill and sometimes underground fight to see the Encyclopedic through; it becomes the inspiring, supreme achievement of the Age of Enlightenment; even his enemies used it for their own intellectual good. Beside the mountainous work, he turned out plays, essays on the theater, reviews on art, and especially novels, now hailed as the forerunners of today's surrealism, existentialism, structularism, eroticism and what-notisms; they still please the scholars, and the general public. What an honor for Diderot, the poor, "snubbed hack, when the "enlightened" Catherine the Great invited him to her court! Almost two hundred years later Professor Wilson and his wife Mazie put their feet in his tracks in and around St. Petersburg, unearthing details of how the atheist and reformist fared there; not too well with the courtiers but famously with the empress; she did not mind his pinching her thighs. She was amused by his suggestions for reform, gave lip service to "philosophy" but stuck to tradition: "Had I faith in him, every institution in my empire would have been overturned."

It would take pages and pages to do justice to Professor Wilson's monumental but far from heavy Diderot. It is a mine of enlightenment on European politics, manners and morals, thought and outstanding people, French, Swiss, Dutch, Germans, British like Gibbon, Garrick, Hume, Sterne. The only American Diderot knew well was Dr. Benjamin Rush, of Philadelphia, who was to become a signer of the American Declaration of Independence (page 572). Wilson scholarship is tucked in 170 pages of notes in fine print, but his text reads like a novel, dynamic and warm in its psychological logic, foresighted, modernistic in its broadmindedness. It took 40 years to write his Diderot Bible; it will be read and consulted in 400 years because it is so definitive, human, and well-written. It is especially charming in its myriad of anecdotes like the one about the Tahitian host (page 589). "Nevertheless the chaplain succumbed to the youngest daughter. He succumbed the next two nights, too, to the older daughters; on the fourth, out of fairness, to the wife."

Historian, novelist, critic, essayist, andphilologist, Mr. Denoeu is Professor ofFrench, Emeritus, Dartmouth College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBetting man's choice: Dartmouth. Then Harvard, Columbia, Cornell

October 1972 -

Feature

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

October 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

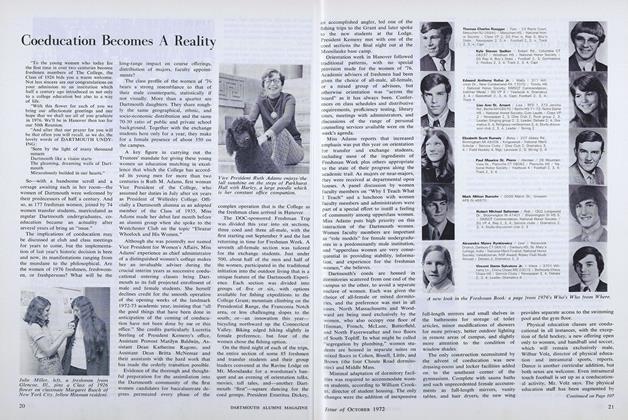

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

October 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureHanover's "Host with the Most"

October 1972 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureHomage to the great god Pigskin: One hundred years of Ivy rivalry

October 1972 -

Feature

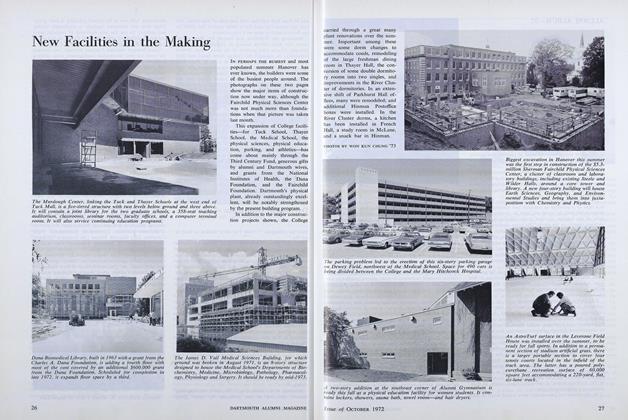

FeatureNew Facilities in the Making

October 1972