ByRichmond Lattimore '26. New York:Charles Scribner's Sons, 1972. 274 pp.$7.95.

Great poets speak to us from other worlds, worlds better in meaning, form, and resonance, though often worse than our own immediate worlds in the natural and manmade horrors occurring there. They speak in voices suitable to such worlds, essentially human but noble, accepting, and perceptive beyond any ordinary human voices. They exist above us, and though they evoke our admiration and gratitude, as men they make us slightly uneasy. Who would want Yeats as a cocktail guest, Milton as a next-door neighbor, Dante or Homer as a fellow worker at the office? Human kind cannot bear very much reality, as a bird told that smug churchgoer T. S. Eliot: for day- to-day use we prefer people more nearly like ourselves, content with a more nearly ordinary life, short views, and a few unsettling but brief moments of perception.

That's why we turn to the minor poets, those men like ourselves (so we flatter ourselves) who rough-hew their human speech into shapely phrases and order their experiences into meaningful forms, and who by giving expression to their own lives suggest that we too are living in a shapely, ordered, and meaningful way. Richmond Lattimore is a valuable poet of this kind. His major work has been as a mediator between our modern, English-speaking selves and such men as Pindar, Aeschylus, and Homer; but like many sensible men he has also recorded his own life in verses that are here collected.

He is primarily an occasional poet: his poems spring from particular occasions in his life, and they evoke other kinds of expression—diary entries, personal letters, intimate conversations, translations (which some of them are), memorial verses, and meditative responses to books, pictures, and events. As he tells budding poets it should be, the material of his poetry is personal and immediate:

only the thing in your hand, the sight that sticks in your eye, the wish that sticks in your heart and will not let you be until it is made art.

Why make such matters verse? Surely it is a conservative impulse, like that which impels the amateur painter, the photographer, the souvenir buyer, even the willmaker—carpe diem, seize and hold the day:

O sky and sand and blue of here and now, how shall we keep you always for our friends and us, and for our sons when we are gone, or save some certainty for all ... ?

Lattimore's verbal amber is a fine answer. In these poems lie embedded his childhood, youth, and maturity, China and the Mediterranean, life and books, seas and towns and railroad trains—including a suitably grim "Last Train out of White River Junction."

A free-lance critic, Mr. O'Hara is Professorof English at The University of Connecticut.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe U.S.-Canadian Relationship

December 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

December 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureHall of Hallmark

December 1972 -

Feature

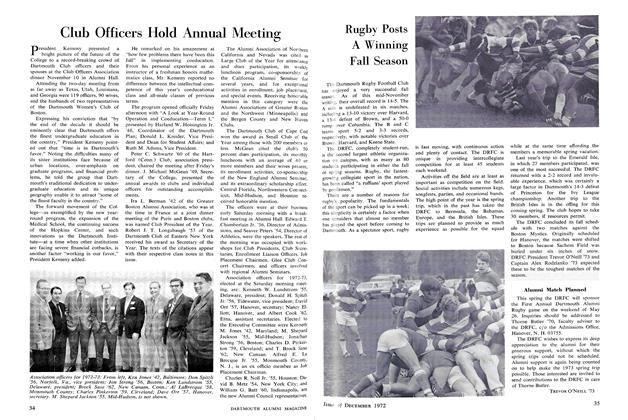

FeatureClub Officers Hold Annual Meeting

December 1972 -

Feature

FeatureRugby Posts A Winning Fall Season

December 1972 By TREVOR O'NEILL '73 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

DONALD O'HARA '53

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Publications

February 1945 -

Books

BooksCLIPPER SHIP MEN

December 1944 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksCOURTSHIP AND MARRIAGE,

November 1949 By Andrew G. Truxal -

Books

BooksPENN STATE YANKEE

December 1953 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksBANKERS' HANDBOOK OF BOND INVESTMENT

June 1939 By John W. Harriman. -

Books

BooksHOURS OF WORK.

JANUARY 1966 By ROBERT M. MACDONALD