An undergraduate research project in biologyBill Schlesinger became interested in heavy metals fromhis experiences as Earth Day Chairman and as Chairman ofthe Environmental Studies Division of the D.O.C., and hasbeen interested in ecology since high school. He combinedthese interests as an honors thesis in biology which hasoccupied much of his time for the last year. The followingarticle represents part, of his work and is an example of oneof the most rewarding aspects of teaching at Dartmouth forthose of us on the faculty. It gives us great pleasure to beable to work with gifted undergraduates who can executefirst-rate studies of intellectual importance and socialrelevance. As is usually the case with thesis advisers, Ilearned as much as Bill did during the project. It is alsorewarding to know that Bill will be pursuing a graduatedegree in ecology next year at one of the finest graduatecenters in the country.

—WILLIAM A. REINERS Associate Professor of Biology

Air pollution on Mt. Moosilauke! The northeastern location of New Hampshire is downwind from major United States population centers. Though it sounds impossible, recent studies by professors and students at Dartmouth have shown that air pollutants are measureable in New Hampshire due to long-distance atmospheric circulation. Several years of study at Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire have indicated that the acidity of rainfall is 10 to 100 times higher than natural background presumably due to the conversion of airborne emissions of sulphur dioxide to a weak solution of sulphuric acid.

Similarly lead, mercury and cadmium appear to be released to the air by various activities of man. These effluents should also be measureable in the airborne deposition on Mt. Moosilauke. David S. Knopman '72 and I with the field assistance of members of the Dartmouth Outing Club (particularly David Kruschwitz '74) began a research project to monitor this deposition in June 1971 under the direction of Dr. William A. Reiners of the Department of Biology.

Mt. Moosilauke, located in central New Hampshire and well known by many generations of Dartmouth men, was ideal for the study. Its high rainfall and elevation and its location in the convergence of air patterns from both the Great Lakes and Middle Atlantic regions, as well as its accessibility to Hanover, were all factors in its selection. The facilities of Dartmouth and generous support by the Richard King Mellon Foundation of Pittsburgh, the Lubrizol Foundation of Cleveland, and the Explorers Club of New York made this study possible. These grants represent part of a continuing program by these foundations and Dartmouth College to involve undergraduate students in practical work in conservation and environmental science. They furnish an important means of relating extracurricular activity to academic pursuits in the field of environmental studies.

At 1000-foot elevation intervals on the mountain slope along the Glencliff portion of the Appalachian hiking trail, our collection stations were established. Each consisted of a precipitation volume measurement device as well as samples collected for chemical analysis. In calculations, sample concentration multiplied by volume gives deposition per unit area. Since this measurement contains both wet and dry deposition, it is called bulk precipitation.

The results of our analyses have demonstrated a longdistance effect of man's activity on earth. Our average lead concentration has been 13.4 micrograms per liter of precipitation. A microgram per liter is equivalent to one part per billion. Our value is lower than the 200 to 500 micrograms per liter concentrations reported in urban areas, reflecting a dilution of emissions with distance, but it is distinctly higher than values of 1.6 micrograms per liter obtained along the west coast. Other studies have indicated that the west to east wind patterns in the United States cause a cumulative increase in pollution across the nation. On a deposition basis our value is eleven times greater than those reported in the mountains of California.

Samples collected during Hurricane Doria of late August 1971 were another interesting aspect of our research. The storm's path brought a flux of marine air to the New England region. Our lead concentrations declined to onequarter of our average value, indicating that our higher average results, derived from continental air, are values elevated over global atmospheric background.

Our analyses for mercury and cadmium have also indicated measurable quanities of these metals in precipitation, although nationwide comparisons are difficult since the results of other similar studies are not readily available. However, our deposition levels of these metals are lower than those reported in Southern Sweden where heavy industrialization has triggered the study of heavy metal deposition from the atmosphere.

Another portion of the study has been to determine the effectiveness of fog and frost in cleaning the air on the summit of Mt. Moosilauke. Since rain droplets and snow cleanse the atmosphere and produce deposition, the persistent fog on the summit of the mountain led us to suspect a higher rate of deposition at upper elevations due to efficient atmospheric cleansing by the numerous condensation droplets in fog clouds. An examination of the results of our collection stations separated by elevation has borne this out. Our windward summit station averaged 16% higher concentration of lead than that recorded at other locations on the mountain.

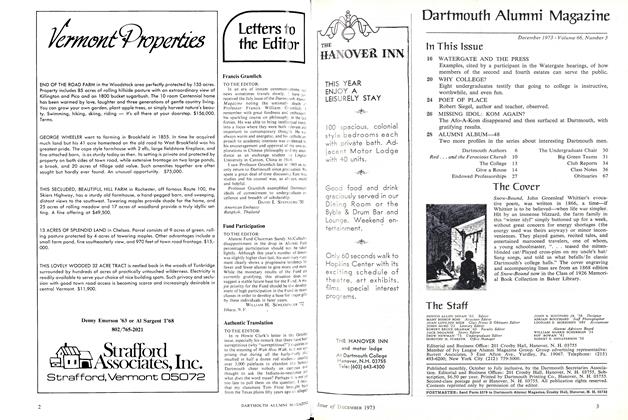

Since plants are effective in collecting fog and frost droplets from the air, we used artificial vegetation in experiments designed to compare rates of deposition in open and vegetated areas. The expected increase in deposition due to vegetational catch was graphically demonstrated.

Yet another part of the project is concerned with the fate of heavy metals received from the atmosphere. Gary Potter, a graduate student in biology, and I analyzed small mammals from a New Hampshire woodland for lead and copper content. Copper, a natural and essential constituent in some animal proteins and enzymes, showed no significant increase in concentration in mammal tissue in older animals. Clearly the animals were not accumulating the metal and contained only what was essential for their life processes. With lead, however, we measured a very significant increase in concentration in their tissues in an age dependent relationship. Young animals contain no measurable lead upon leaving their nest and thus show its unessential nature in biochemical processes. The mammals subsequently appear to accumulate lead as they forage in the forest floor for their food.

What is the meaning of all these experiments? First of all, they show yet another example of the global effects of atmospheric pollution of man's environment. More importantly, however, they offer several warnings for mankind. The use of leaded gasoline currently consumes 20% of the annual 1.3 million tons of U. S. lead production and releases most of it as small airborne particles. This practice is beginning to cause health problems in the air in urban areas. Concentrations of lead in the rainfall in cities approaches the U. S. Public Health Service drinking water limit of 500 micrograms per liter. At the same time, long-distance transport of lead is measurable, as is accumulation of lead in the tissues of woodland small mammals. It is doubtful that there are harmful environmental effects of lead deposition in New Hampshire, but the fact that it can be measured here speaks a warning for areas where lead is emitted in quantity.

Similarly, airborne cadmium releases from processes related to the smelting and treatment of various metallic ores and from the disposal of products containing cadmium have led to the measurement of cadmium pollution as well as a description of the effects of cadmium pollution in areas near airborne emissions. In eastern Pennsylvania, for instance, the regrowth of vegetation has been inhibited in forest fire areas near a zinc smelting plant.

Our results also help explain mercury concentrations found in the lakes of remote areas, such as Silver Lake in Green Mountain National Forest. The entire question of the health aspects of mercury in fish is viewed with conflicting opinion by various scientists. The measurement of the amount of mercury received from the atmosphere in precipitation which eventually finds its way to surface runoff should be helpful data in this controversy.

Artificial vegetation was used to collect fog and frost droplets from the air in an experiment designed to compare ratesof deposition in open and vegetated areas.

THE EDITORIAL BOARD which assisted the AlumniMagazine with this first supplement devoted to undergraduate course work consisted of Charles M. Cald-well '75, Anne Derry S, Ronald J. Falk '73, Wayne S. Leibel '73, George A. Middendorf III '73, Linda Yowell S, Michael D. Piatt of the English Department, and Dennis A. Dinan '61, Director of Alumni College. The Faculty Advisory Board for this and future issues consists of James J. Anderson, Assistant Professor of Biology; Marilyn A. Baldwin, Adjunct Assistant Professor of English; James A. Epperson, Associate Professor of English; Colette L. Gaudin, Associate Professor of Romance Languages and Literature; David D. Gregory, Instructor in Anthropology; Joseph D. Harris, Professor of Physics; Roger D. Masters, Associate Professor of Government; Gregory S. Prince Jr., Adjunct Assistant Professor of History; Franklin W. Robinson, Assistant Professor of Art; and Winthrop A. Rockwell '70, Assistant to the President.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Future of Liberal Arts Education at Dartmouth

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Men and the World: Three Views

June 1972 By ALBERT H. CANTRIL '62 I, THOMAS F. BOUDREAU '62 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureWhitman at Dartmouth—100 Years Ago

June 1972 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE SAMPLER

June 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Myth of the Munich Analogy

June 1972 By STEPHEN C. THEOHARIS '71