Identity in the heart of darkness

Power means to make one's own meaningsin the world. This is the beginning offreedom's liberation from him who wouldoppress it.

THAT is the way Professor Hoyt Alverson, chairman of Dartmouth's Anthropology Department, concludes his book, Mind in the Heart of Darkness. Published in 1978 by Yale, where Alverson earned his graduate degrees, the awardwinning study ostensibly concerns the Tswana of South Africa and Botswana, a people who have been coping with the experience of colonial domination for more than a century. As much as it documents the life of a particular people, however, the book also concerns a conception of human identity and consciousness. Part of Alverson's thesis is that in order to understand another culture Tswana culture in this instance the observer must understand what people in that culture believe it means to be human. The book's sub-title, "Value and Self-Identity Among the Tswana of Southern Africa," is therefore meant to be taken seriously. Alverson maintains that understanding on that level will never be achieved by the so-called objective observer who reports on appearances. A valid interpretation of another culture's experience, he says, requires looking beyond appearances; it requires making contact with the meanings people attribute to exPerience. Those meanings, it turns out, are remarkably resilient. They also are familiar, which is one of the claims Alverson's work has on one's interest.

Because Mind in the Heart of Darkness is so thoroughly a book of ideas, perhaps the best way to talk about this professor is to talk about what he professes. In both his methods and his conclusions, Alverson does a different kind of anthropology from the ordinary. His ambition in the book is to show that "the experience of inequality or domination is not the same thing as the institutional structure of inequality or domination." Not a new notion, but hardly self-evident. Through an analysis of the ways that the Tswana use language through a study, based on hundreds of interviews, of what people mean by what they say about their values he arrives at evidence to support that notion. The reason structured inequality is not equivalent to experience, he argues, is because "a person has the power to invest the world of his experience with meaning." The inside world is not determined by the world outside.

What he is aiming to avoid in his work is the point of view of many of his predecessors in looking at non-industrial people the point of view, one might add, of many Westerners looking at the rest of the world which ignores consciousness and will, making the subjects of investigation actually objects. Alverson is working within a philosophical tradition that holds that understanding of the world always is mediated by the consciousness of the observer. A description of the world always entails a statement about a particular way of seeing the world. In the very act of seeing, we impart meaning to what is seen.

"We are doomed to live in a world of meanings," Alverson writes. "Even when we are most certain that we have grasped the 'facts,' the 'things-in-themselves,' we have grasped meaning-for-us. This is our relationship with the world, which we call understanding." This point of view makes a difference, not only in the attitude of the anthropologist but also in the kind of information that can be reported. Experience can be seen, but the meanings of experience cannot, and it is those meanings that Alverson seeks. He claims that "the supposition that people and society can be made objects can be made thing-like to render them fit for the investigations of science, destroys the phenomenon of con- sciousness before inquiry has begun." So in his report on the Tswana, he makes no claim to be bringing the reader "a world of facts." Rather, he reports on how he sees the Tswana as seeing themselves. The effort, then, is the self-conscious act of the observer interpreting the subject's consciousness of self.

DURING a recent conversation Alverson described his field, in general, as an attempt to integrate the study of all' human history and pre-history as well as our biological evolution. As far as anthropology is concerned with contemporary society, he added, it seeks to study "the entire breadth of human cultural expression." Discovering and understanding differences in human societies is not the primary goal, however. The fundamental object is to arrive at general propositions about the nature of human culture and to achieve an understanding of how culture characterizes our existence as a species.

The concept of human culture is what gives a common purpose and direction to the activities of the six or seven people in the Anthropology Department at Dartmouth. Aside from Alverson's own interests in linguistics and economics, their various specialties include biology and genetics, music, sociology and demography, art, and classical archeology. Anthropology is considered a science a "soft" science, some say but the different branches of the discipline demonstrate various degrees of the concept of science as the use of the experimental method and formal techniques. Linguistics and physical anthropology might be considered the most scientific in that regard, Alverson explained, while the study of music, religion, and art in anthropology is closer to the kind of work done in the humanities. "In general, the results we obtain often are not the results of axiomatic theory testing," he added. "We don't have axiomatic theories as in physics. Our claim to following the scientific method of producing falsifiable hypotheses is more like that in the earth sciences. We tend to work with broad, empirical generalizaTions, translating them into multiple, working hypotheses, and then testing them against crucial touch-points with the empirical world in the course of field work or comparative work of some kind."

Alverson's combination of interests in linguistics and economics is an unlikely pairing that he has found to be productive for investigating indigenous people's perceptions of the processes of rapid cultural change brought about by the impact of modern institutions on traditional societies. He credits his interest in southern Africa to the influence of Richard Henderson, a professor he studied under at Yale, whose work was concerned with understanding traditional systems in the light of colonial and industrial processes. Alverson's use of linguistic methods in anthropology allows him to focus on the ways people semantically express and represent experience. The linguistic approach allows him to emphasize the "conscious perceptions of actors caught up in the vortex of world economic change." The success he has achieved with his book in conveying the mind of the Tswana to "the mind of his readers was recognized last year by the presentation of two prestigious awards: The Herskovits Award from the African Studies Association for the best book on Africa in 1978 and the Chicago Folklore Prize.

A year's research for his doctoral dissertation, a study of the responses and adaptation of black migrant workers to the conditions of mining and industrial life, took Alverson to South Africa for the first time in 1966. He was hired as a consultant by five industrial companies to report on inefficiencies in the organization of work, but at the same time he was looking for ways to improve production he also was making his own observations on the workers' experience in the compounds. Asked about the implications for his research of being white in a world where color makes such a difference, Alverson conceded "an inherent difficulty in walking both sides of the line." It was up to him to make his presence credible to workers and to establish rapport with both blacks and whites, but he found that efforts to make personal contact with black line workers inevitably led to alienation from white supervisors, while attempts to reach an understanding with Afrikanners made him look suspicious to Africans. He had a rudimentary knowledge of the workers' language and the dialect of the compounds, but he still was forced to rely extensively on interpreters a situation, he admitted, that resulted in a somewhat "formal" tone to his thesis.

Although he accumulated a great deal of data and uncovered new information about the conditions of industrial life, the feeling he had of distance from his subject the nagging sense that he "didn't get to know the black workers as human beings in the fullest way" gnawed at him, Alverson said. This problem he saw in his thesis led him to undertake a return study in Botswana the homeland of the Tswana, many of them migrant workers in South Africa where he could become more intimately acquainted with the workers' lives, with their professed motives for seeking work in the mines and industry, and where he could become more familiar with their experience of "being people in two worlds."

He never attempted to publish the doctoral thesis, Alverson explained, because of the amount of data it contained that could have been misused for "further exploitation of black workers." The later work, which he found much more satisfying, was conducted during a series of visits to a variety of town and rural settings in Botswana and forms the bulk of his book. Asked to summarize his accomplishment, he said that "the contribution I think I was able to make was to really be able insofar as it's possible for an outsider to get inside their hearts and minds. I think I was able, through language, to represent for Western readers something of the meaning these people bestow on the daily conditions of their living, including especially mine or industrial labor. I attempted, in other words, to provide the subjective correlate to the objective material description that I tried to make of their economic life."

A large portion of Alverson's findings is based on a year's residence in Botswana with his wife and two sons. Having his family with him was important for establishing credibility, he explained, because in most pre-industrial societies a person is not considered fully an adult until he or she is married and has children.

"Because I was a husband and father I could enter the system with a certain entitlement to respect," he said. The Alversons lived in a single-room hut, 18 feet in diameter, made of mud and dung and covered by a thatched roof. Summers in Botswana are hot 100-degree temperatures are not uncommon and there is regular frost and a sharp wind in the winter. Alverson described the climate as "equitable" enough to permit most of the chores of daily living to be done outside. The family primarily used the hut for sleeping or to get out of the midday sun.

They brought with them a minimum of material goods partly because they were living on a shoestring budget and partly to avoid setting themselves apart from their neighbors. For furniture they had cots and a few trunks, one of which served as Alverson's desk and library. They cooked on a paraffin stove and hauled all their water from about five kilometers away. Because of the scarcity of water, they bathed about once every three weeks. Alverson had with him a small truck he used for transporting their belongings and provisions, but for daily transportation he used a bicycle.

The Spartan camping conditions, the difficulties with sanitation, were a way of life he and his family adapted to quite well, Alverson noted. The greatest problem he experienced was adjusting to the almost complete lack of privacy in the community. "The almost totally communal character of living there meant you could never be assured that you could wall yourself off even for a short time. You even had company if you tried to go for a walk. The fact that people wanted to talk to me was good for my research, but for a period of 15 months during my first visit I found that I could hardly get away from anybody. I'm a very private person by disposition. I'm not a group type. So that was a most strenuous experience for me to be pleasant, to be aware that I had to be available to this community on terms pretty much dictated by it. It was very much counter to my personality."

Some of Alverson's students also find him to be private by nature "not all that approachable" was the way one of them described him. He is well-liked by the students he is close to, another noted, but "there are a select few" in that circle. A colleague in the Anthropology Department said Alverson was his "role-model" as a teacher, citing the "extraordinarily high standards" he sets for students and his ability to provoke independent and creative thinking. Some students find those expectations uncomfortable, Alverson's associate said, remarking that the best students in the department tend to be attracted to his courses, while those who are less ambitious tend to shy away. Another colleague said Alverson has a reputation on campus for being outspoken "courageously so or abrasively so, depending on one's point of view." He added that Alverson's view of what an educational institution ought to be is sometimes at variance with what he sees at Dartmouth, and also that he seems to be at ease in his role as a gadfly.

THE organizing idea for Alverson's book stems from some library research he did to find evidence for what has been called the "scars of bondage" theory a social and psychological claim, frequently applied to the experience of American blacks, that the experience of structured social inequality has a scarring effect on the psyches of the vulnerable, dominated population. According to this conclusion, he explained, the psychological wounding becomes as much a problem as the actual oppression, and the resulting mental and emotional disability becomes itself part of the issue. His reading showed this to be a common notion, but he found little evidence to support the idea. "The finding I came up with," he recounted, "is that despite the hardships of structured inequality, there isn't much evidence for the psychologically debilitating effect you might predict intuitively."

In order to prove his contrary hypothesis, which wasn't possible by using only the secondary data in libraries, Alverson wanted to go to an area of the world to study a group of people who "have lived out their existence in the lowlands of the colonial system." In southern Africa, although he found that the groups of people who were worst off under the colonial economic system showed self-effacing and denigrating attitudes, there was not the long-term and deep-seated scarring that had been claimed. "I had an inkling this would be the case from my library research on black Americans," Alverson said, "and this hunch was confirmed by my research in Botswana. Despite the conditions of their material existence, people were living a very rich cultural life. There is a resilient, lively, vivacious, and self-contained people and culture."

The "Heart of Darkness" reference in the title of his book, Alverson noted, is "gratefully" appropriated from Conrad, who presents the heart of darkness in his novel as the interior experience of Kurtz, an individual cut loose from the restraints and moral codes of Europe. In the title of his book, Alverson alludes to Kurtz's creation of an empire in the middle of the jungle, where he comes to control a group of primitive people. The illusion Kurtz creates of being all-powerful, unbound from the proscriptions of European life, causes him to lose his mind and to cease to be fully human, Alverson pointed out. Kurtz becomes no longer a social creature; in some senses he becomes a monster. That experience of unrestrained power and unfettered domination graphically depicted in the recent movie ApocalypseNow is called the heart of darkness, and Alverson means to draw a parallel to South Africa "the white man's empire, incredibly powerful and dominant." "Mind," of course, is the Tswana, who maintain their integrity and human consciousness in that experience of incorporation within the heart of darkness.

The technical term describing the apPraoach Alverson brings to the study of that experience is "phenomenological" a word loaded with philosophical ramifications. By defining his approach as phenomenological he means that reality is reality only as it is known. In other words, "There is no such thing as an empirical world that exists independently from the way it is known, because to know the world is already to know it in a certain way." The ways we know the world are by virtue of culture, traditions of knowledge, and attitudes toward experience. "A Phenomenologist argues that reality is to be discovered in experience," he explained, "rather than by making claims about an external world." Those who hold contrasting viewpoints call themselves positivists or empiricists, and they argue that there is, in fact, an objective and stable world "out there" that gives rise to the stability of our thoughts and ideas.

These differences have important practical implications for social research, Alverson claims. The empiricist view that he argues against tends to minimize the interpretive importance of the observer and reports, according to Alverson, as if "the social structure had a pen jammed in its hand and was writing its own story." As far as he is concerned, the ethnographer never eyeballs reality: "Whenever you take the view that you are describing what is really real, you'll avoid all sorts of things that don't lend themselves to that belief. You'll speak about the most obvious. You'll simplify or limit your vision to what can fit within the requirements of so-called objectivity so-called empiricist science. To my mind, that stance destroys for the investigator much of what he ought to be looking for." What Alverson tries to do in his study is to look for what is least visible the meaning of experience. Language is his tool, his means for discovering the thoughts, feelings, and beliefs that determine self-identify.

As he explains in his book:

To deal with Tswana experience, and in particular "self-experience," we must turn to the Tswana speaking using their language to communicate their beliefs. Their language-inuse is our principal mode of access to the private, interior experiences that comprise selfidentity.

Any inquiry into self-identity runs the risk that the researcher will create a reality by his very choice of initial questions. Questions in human language usually rest on numerous presuppositions of fact and belief. Respondents often give answers based on astute but ad hoc elaboration of the ideas embedded in seemingly simple and straight-forward questions. When opening my interviews I tried to avoid this pitfall by reciting a number of well-known Tswana proverbs and aphorisms which I had interpreted as reflections of cultural principles basic to the individual's beliefs about his own social identity and possibly his self-identity. All of these sayings contained as central themes the three questions: what is human nature (bothomotho), what is a proper, adult Tswana (monnamtota), and what is the ideally good life (bothelojo bontle). While I did not assume these were necessarily crucial for the Tswana in defining self-identity, I did assume they would open the inquiry with a minimum of direction from me.

Younger Tswana and almost all women were puzzled or confused by my commentary and discussion concerning "human nature." Younger people and most women claimed they did not think about such issues, and they suggested this topic was to be found only in "deep" or very old Setswana, of which they lacked knowledge. Older men differed markedly from the younger and from women in being very eager to express their views on the topic of "essential human and individual nature" and to hear "views from America." In contrast to the considerable variation I found among the Tswana on such topics as "things I want to do," questions about essential human or individual nature elicited remarkably uniform responses, including consistent citation of numerous homiletic proverbs and parables. This fact leads me to believe that there must be a concept of "essential self-identity" that comprises part of the philosophic stock of Setswana knowledge and is transmitted from generation to generation in the reflective conversations that older men reserve for themselves.

He maintains that "in no human society are the deeply held beliefs that comprise self-identity reliably signaled or designated by overt behavior the surface of social life." The essential goal of his phenomenological approach and the use of linguistic analysis is to get below the surface. He says that his report on the Tswana "is based on the premise that a person's conscious and sincerely held beliefs about self-identity as such and himself in particular are important and valid indicators of— or even the basis for what he objectively is." That premise, he points out, appears to be shared by the Tswana.

How does even the most sensitive researcher, asking the most sophisticated questions, know for sure that he is communicating with his subjects on that level, I asked Alverson. How could he know that in his attempt to get below the surface of social behavior he was not seeing just another surface another ploy used as yet another stratagem for selfdefense (this time against the prying questions of the anthropologist) and not really the "mind" of the Tswana? Why should he think that what the Tswana told him they believed was what they actually believed?

People revealed strategies for coping with the world, something they wouldn't have done unless they had confidence in him, Alverson replied. In talking with him, people "exposed themselves," he said. They made themselves vulnerable by volunteering information that could have been used against them. Alverson also pointed out that because he was a full-time resident in the villages, he would have eventually noticed major inconsistencies, had there been any, in what people said about their lives. He added that when he was talking with a group of people and someone would make a far-fetched statement, others would jump in and say, "You can't fool Alverson he lives here." Barring dramatic changes in the social situation that he observed, and barring fundamental changes in our own culture's approach to knowledge, Alverson asserted that the general tenor of his findings could be replicated by another researcher who shared his method and point of view. He believes a culture is open to reading much as a text can be read. As long as the text itself remains constant, and as long as the act of reading means the same thing for different readers, it is reasonable to expect a certain amount of stability in interpretation.

I proposed to Alverson that his conclusions about the human ability to define and maintain a meaningful self-identity from within even in the most inhuman circumstances is essentially optimistic. Equally optimistic, and perhaps less wellfounded, I suggested, are his assumptions that the deepest meanings of one person's life-experience can be accurately un- derstood and then reported by another. Isn't that unavoidable difficulty com- pounded when a difference in culture intervenes? The ordinary sort of communication between an author and readers in a single culture is precarious enough to begin with. Hasn't this project multiplied the chances of misunderstanding by depending so absolutely on the success of communication between Alverson, the white American, and the Tswana, the black Africans?

Alverson agreed that the reader of his book is two interpretations removed from the! life of the Tswana, but he accepted that situation as a fair occupational hazard of anthropology. If the acts of translation from one culture into the understanding of an observer, and then from the observer into a book for a reader are optimistic, he said, then he believes he has reasons for the optimism: "They have something to do with the universals of human existence. I do not believe that cultural differences create unbridgeable gulfs. I believe that underlying cultural differences is a great deal of human uniformity, and that sedimented in all language is participation in universal language. The task of translation from one culture to another is only quantitatively different from the task of translating from one person to another. There are two gaps, but that would be true of any author who writes about anything. What is remarkable is that languages spoken by widely different peoples are, in fact, so translatable."

The usefulness of Alverson's approach to understanding cultural experience depends, in part, on the complexity of the society the observer wants to study. In a complex society, such as our own, the bulk of a society's functioning is outside the consciousness of individuals, while in a simple society each individual's understanding incorporates much more of the total cultural experience. "In a sense," Alverson explained, "asking so much of personal consciousness works best when consciousness is most embracing of the total social reality." That is not to say, however, that as societies everywhere rapidly become more complex that the validity of the phenomenological approach vanishes. It begins to lose its value for understanding the large-scale dynamics of social change, but for understanding the experience of particular communities, groups, families, and individuals the phenomenon of an ethnic ghetto in a large city, for example Alverson believes the approach is pertinent. "From the point of view of problems where understanding the meaning of experience is important psychiatry, for example this method might have utility for as long as we have human groups. The more we use this method in the study of human groups in complex societies, the less tyranny will be posed by purely statistical studies."

As an example of a practical application of his work in Botswana, Alverson cited some consulting he did in the area of agricultural development, helping the government find ways to reduce the country's dependency on South Africa for foodstuffs. (About the size of Texas, with a population of three-quarters of a million, Botswana has roughly 100 acres of arable land for every family but still imports half of its agricultural produce.) Agricultural development programs have had generally terrible success rates almost everywhere, Alverson said. "We've tended to see the peasant production system as inherently inefficient, and have tried to eliminate it by introducing new technologies and new relationships of production. That is the mistake that has led to failure." Instead, he has tried to make planners aware of the cost-effectiveness of the peasant mode of production. The traditional practices of crop-rotation and letting land lie fallow make more economic sense than energyguzzling programs of fertilizer production, and animal traction is most often cheaper than using machinery. In addition, he argues, the traditional arrangements for land ownership and labor obligation ought to be seen as resources and not obstacles. Alverson tried to focus on the peasant point of view in agricultural production and to bring that perspective to the government "in a light that makes it possible for economists and agronomists to see that there is something here worth preserving."

Alverson's major criticism of his own work in the project of attempting to understand and explain the life of the Tswana is that in his book he tended to describe people's values and perceptions independent of a description of their social positions. Because of wealth differences enormous by Tswana standards but minimal by ours ideals that are shared by all are realized by only some. The ideal of controlling land and cattle, for example, is more out of tune with some people's existence than with others'. He wishes he would have made more of the tension between Tswana ideals and the reality of daily living, and he regrets he didn't call more attention to the degree of stratification within Tswana social groupings because so much of the Tswana ideology works within a class system. In general, however, he is satisfied with his research and views his work in Botswana as complete. "I think I've done a lot there and I want to move on to other interests," he remarked. "But if the country feels strongly enough about my work to bring me back as a consultant again, I'd feel a certain obligation to respond."

As a teacher of anthropology wanting to impart an appreciation for his discipline, Alverson tries to create for students first a sense of the strangeness of a social form or custom, and then a deeper sense of the "commonsensical familiarity" of what at first appears exotic or foreign. More than that, however, he sees his task

as creating a rational basis for skepticism. In fact, he added, creating a continuing and rational basis for doubting is what gives liberal' education meaning. The notion at first seems ironic teaching students to doubt what they've been taught but in Alverson's view the activity is more creative than destructive: "Skepticism is a key skill for being a rational human being. The only motivation for change is that one's skepticism is always greater than one's belief." In a fashion, he wants to create a radical perspective in students "radical" in the basic sense of questioning things at the root. That enterprise is worthwhile, he says, but troubling. "Students leave my courses vexed," he observed. "They tell me I assault their identity. I put them through strenuous intellectual and moral experiences that sometimes are painful." He appreciates the freedom at Dartmouth to maintain the spirit of questioning in classrooms, he said, but senses a lack of incentives for encouraging inquisitiveness in life here generally. It would be a great step, he suggested, if the spirit of the classroom could extend further out into the College. Alverson said his decade of work in southern Africa particularly his work on his book has been more than just an intellectual exercise for him, more than a series of research projects. During the last of our conversations, he remarked that as a result of the experience he has become "astutely skeptical of my own culture" and sharply conscious of the materialism that characterizes it critical of the attempt to solve problems by increasing production and consumption. As an example of the change in his perceptions, he mentioned an instance of what he sees as a common distortion of the concept of "needing" something: His 14-year-old son announced he "needed" a pair of expensive skis this past winter, which occasioned a lengthy and productive discussion between father and son about the difference between "needing" and superficial desiring.

In the introduction to his book Alverson describes what he wrote as "a philosophical meditation as much as it is a report of my own observations." He said he was wrestling with the dilemma of reconciling "the freedom and creativity of thought and language with the material determinism of society and history." The answer he supports, that "a belief in one's power to invest the world with meaning and belief in the adequacy of one's knowledge for understanding and acting on personal experience are essential features of all human self-identity," has significance beyond the Tswana.

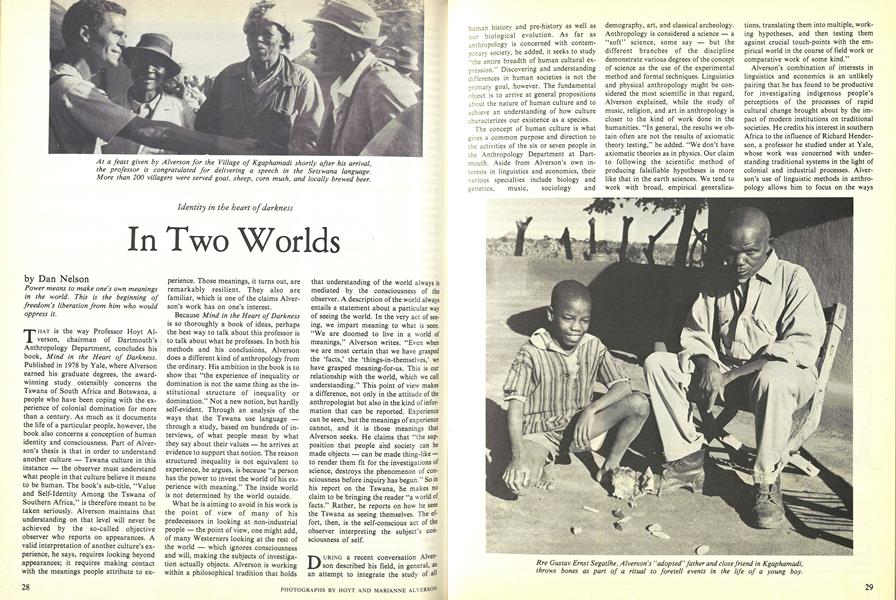

At a feast given by Alverson for the Village of Kgaphamadi shortly after his arrival,the professor is congratulated for delivering a speech in the Setswana language.More than 200 villagers were served goat, sheep, corn mush, and locally brewed beer.

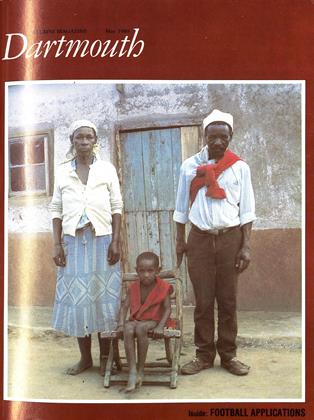

Rre Gustav Ernst Segatlhe, Alverson's "adopted" father and close friend in Kgaphamadi,throws bones as part of a ritual to foretell events in the life of a young boy.

Migrant workers, just home from the South African mines, celebrate their return.

Alverson participates in prayers sung by the women of Kgaphamadi before a meal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Article

ArticleAlchemist in Miniature

May 1980 By Michael Colacchio '80 -

Article

ArticleScientific Humanist

May 1980 By M.B.R -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

May 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticlePainting Medicos Have Both "Life" and "Work"

May 1980 By D.C.G -

Article

ArticleVox

May 1980 By Norman R. Carpenter '53

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

MARCH 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

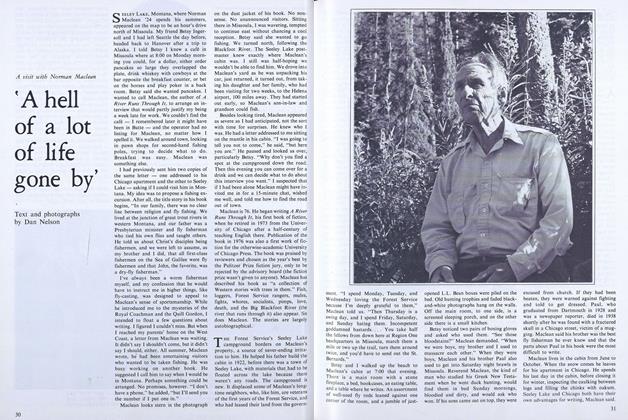

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureShark Authority

JUNE 1968 -

Feature

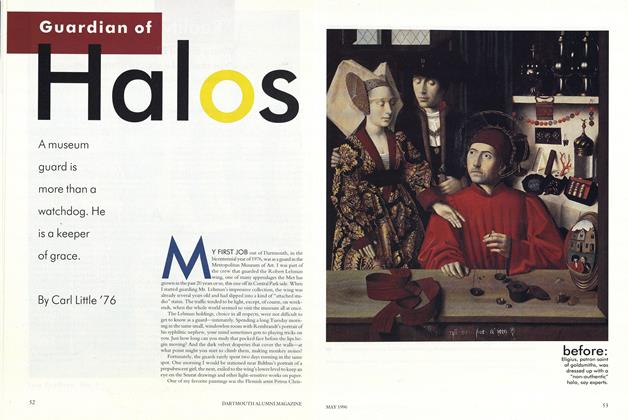

FeatureGuardian of Halos

MAY 1996 By Carl Little '76 -

Feature

FeatureGetting Gored by a Rhinoceros Was Only Half the Experience

NOVEMBER 1988 By Emily Hill '90 -

Feature

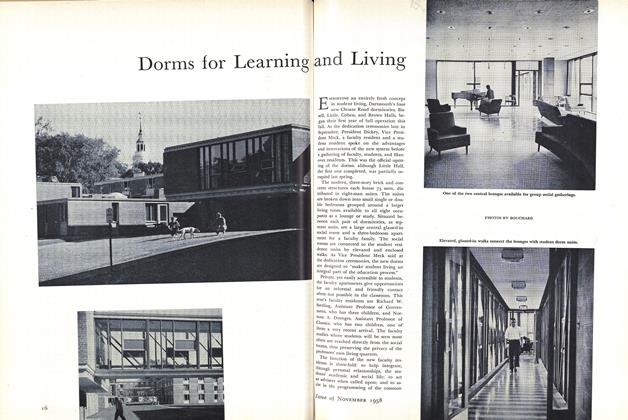

FeatureDorms for Learning and Living

By J. B. F. -

Feature

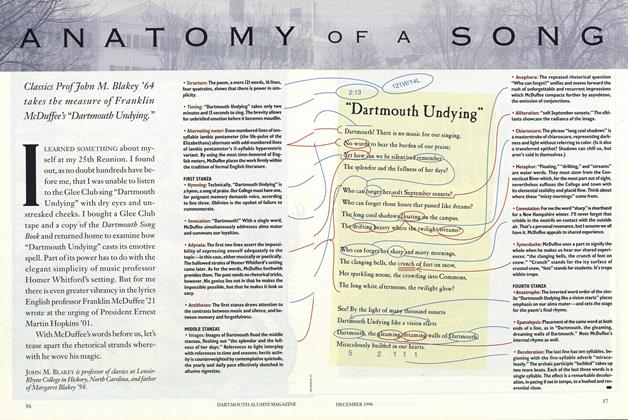

FeatureANATOMY OF A SONG

DECEMBER 1996 By John M. Blakey '64 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to the College

JULY 1967 By STEVE GUCH JR. '67