An issue that appears to have been ignored in recent years needs to be raised once more, and re-examined with specific reference to Dartmouth students. The issue is this: what are black students feeling about the College now and the whites around them.

"We're still a minority," says Pat Ferguson '76, a cheerleader and member of the Afro-American Society's executive committee. "Some blacks get used to being isolated in a white community, and the system of studying and academics after the first term ... some adjust to the environment, or learn to live with it. Others never really do.

"It's a hassle, too, being a black woman here. At fraternity parties, I feel out of place, and when our dorm [Woodward Hall, now all female] invites a house over, I'm not sure I should help pay for the beer since I don't really want to stay around. Some of the older professors still don't feel women should be here, so they grade you just a bit lower because they feel women just can't do the same work a man can."

Racial prejudice? Now more subtle, in the form of what Ferguson describes as "Overniceties." She says, "I'm out to be one of the class, but some profs, will go out of their way to let you know that they know you, as a black, are there."

Representation, she says, is a particular problem now. In the future, she hopes a need for "representation of all minority groups here" will be recognised. "It's hard for a group of people to get by without a speaker ... how are people to know what your problems are?" With the increase of blacks in the administration, she says, new voices will be heard and the problems will be dealt with." Ferguson hopes too, 'hat blacks will become convinced that the activities on campus, teams and organizations "are not all white, but are Possible to be joined. People will then see slacks around, and not just associate them with the Afro-Am."

Gary Gipson '74 from Houston, Texas never experienced integration until he arrived in Hanover: "At home, I still never see as many whites as I do every day here." But integration does not necessarily mean an end to isolation. At most urban universities, blacks can easily drop back into a surrounding black community. "Here, more than anywhere else," Gipson says, "the College's blacks are the black community. Thus the total impact of black culture with society is the responsibility of the blacks here."

Things have changed since the fall of 1970, according to Gipson. "When I arrived here," he explains, "the burning issue was where blacks sat in the dining hall. It seemed whites were disappointed because they felt the idea of having blacks here was integration. Well, football players and fraternity members sit together. They all have common interests, grounds for solid human relationships, as do we. Now, people are not as hungup about this. There are more blacks here now - it was hard to ask twenty-five blacks to integrate Dartmouth - and that means having a cross section of blacks in terms of backgrounds, interests and experiences, which results in blacks getting involved more and becoming more visible."

Is there tension between blacks and whites? "To a degree, yes," Gipson says. "Mainly because we as a people are not dead, and are not therefore divorced from the impact of the past; we are alive. Many whites feel bound to defend themselves against charges of racism. That, though, is not the question. Whites need the intellectual courage to divorce themselves for a time and analyze themselves in a historical sense. Admit this is a racial society, have the courage to deal with that, and go on from there. Call it an error, there's no grudge, examine yourself, go on to alternatives ... let's deal now with now sorts of things."

"Being a political minority is a parity problem," says Gipson. "It's part of Dartmouth's aura and tradition that Dartmouth men are very much like each other. Now they are not like each other at all, but actually complement each other in a very, very fruitful way, with different backgrounds and experiences. Some see a danger, though, in what black students want. They fear ethnic divisions, fear that it removes objectivity. Poor black political representation tells me that. For groups like the College Committee on Standing and Conduct [CCSC], people don't believe blacks are capable of justice in any sort of responsible position. They seem to feel that if the CCSC and other groups were broken down for peer group representation, it would show a 'lack of objectivity.' I call that a bad case of a lazy mind, a mind not out to deal with the current manifestations of past errors."

"You're always learning about black and white people," says John Hannah '74. "Hanover is such a small place that you're always bumping into people. You can see how they react to different situations, whether they shed their values and experience gut reactions. You can see contradictions: People will tell you one thing and then you can see them react differently for the whole year."

"Race relations here are like those at home in Englewood, N.J." Hannah asserts. "I went to school with whites; relations appeared good, but when people began to discuss the issues, you found you were miles apart in terms of thought, especially in terms of black peoples' demands for an end to things like black oppression. In the classroom at Dartmouth, a professor will tell you when you begin to discuss the issues that you're not being objective. How can you be? We're dealing with subjective subject matter."

"The situation here reflects that of the country," Hannah continues. "Whites still don't understand what blacks are talking about ... black issues are not white issues. Who cares if the gap between white and black incomes is widening? The country is tired of trying to deal with those problems. Richard Nixon offered little to us, yet he was elected. Many professors feel incapable of dealing with racial discussions because students may begin to reflect their real value systems."

Says Gipson of the future: "Things can get better or much worse. Better in that under the impact of reflection on culture and education about the country's makeup, Dartmouth can become a really American institution. Or, worse, like the country, it can get tired and decide the efforts of equal opportunity are too expensive and too much trouble.

"I'm hoping, and that's the end of it... I'm hoping."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturemAgnA CARTA: Seventh Crisis of John Plantagenet

November 1973 By CHARLES T. WOOD -

Feature

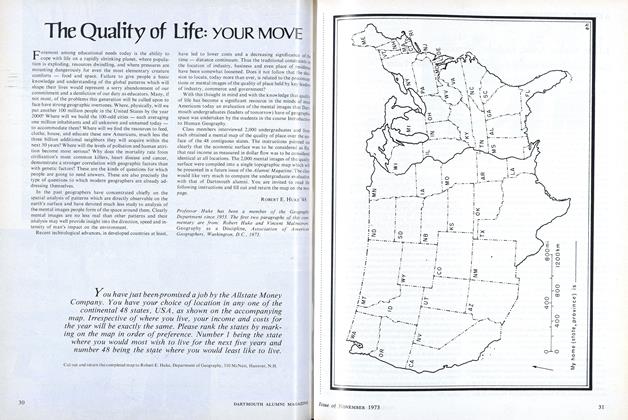

FeatureThe Quality of Life: YOUR MOVE

November 1973 By ROBERT E. HUKE'48 -

Feature

FeatureA PORTFOLIO OF THE Dartmouth Cemetery

November 1973 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1973 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleEditor, Banker, Artist, Engineer, Physicist Dartmouth's Post-War Refugee Students 25 Years Later

November 1973 By HARRIET GUNDERSEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

November 1973 By RICHARD K. MONTG.OMERY, C. HALL COLTON

Article

-

Article

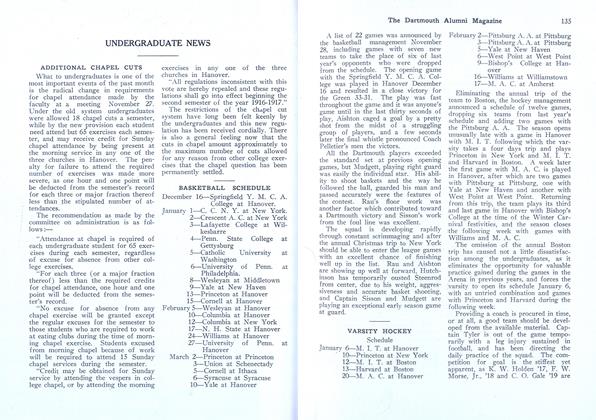

ArticleADDITIONAL CHAPEL CUTS

January 1917 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE WAR FUND

July 1918 -

Article

ArticleCLASS ORGANIZATION AND CLASS FINANCES

June 1929 -

Article

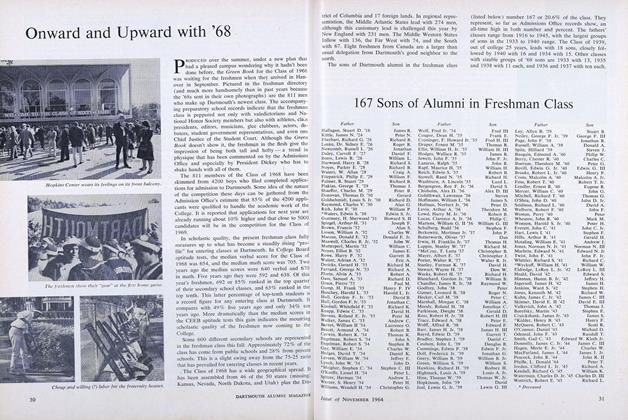

Article167 Sons of Alumni in Freshman Class

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

January 1935 By Hap Hinman '10 -

Article

ArticleIF YOU WANT TO PLAY, YOU'VE GOT TO PAY

May/June 2008 By Lauren Smith '08