Edited, by Russell Fraser '47.Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, Riverside Editions, 1969. 438 pp. Paperback.

Contemporary critics are finding that Oscar Wilde was more than an Irish snob trying meretriciously to climb in London society, a critic delighting in fin de siècle paradoxes, a playwright of trivial comedies, a Dorian Gray imprisoned for homosexual scandals, and a green-carnation failure who under an assumed name met premature death in Paris. A Renaissance scholar, Russell Fraser, Chairman of the Department of English, University of Michigan, while conscious of Wilde's weaknesses as writer and human being, reassesses his strengths. In the 22-page introduction he suggests that Wilde frequently in his plays "managed what is almost a return to the brilliant artifice of the Renaissance: stichomythia, the poetry of wit. One wants to enlist him, in his best and highest moments, in the company of Shakespeare and Congreve."

Mr. Fraser goes so far as to say that no one else in the English drama deserves that particular praise and that "there is more to the Yellow Nineties than the ineffectual effusion of very young poètes maudits over the clay pipes and tankards of ale in the upper room of the Cheshire Cheese."

The introduction is particularly useful in that it attempts to relate Wilde to the social currents and leading writers of the nineteenth century: Robert- Louis Stevenson, Walter Pater, John Ruskin, William Morris, Max Beerbohm, C. M. Doughty, W. H. Hudson, Conan Doyle, Thomas Hardy, Arthur Machen, Francis Thompson, Charles Stewart Parnell, and Keir Hardie. Mr. Fraser describes Wilde as the apotheosis of the mauve decade, and the introduction would give him "pride of place."

Mr. Fraser astutely points out that if on the one side Wilde was kindred to Walter Pater he was, on the other, kindred to Henrik Ibsen. Mr. Fraser remarks that it is curious "that the nineteenth century which saw the repudiating of the intellect culminate finally, and logically, in solipsism was also the century in which the claims of the intellect began to be asserted again: Karl Marx, the Schoolman as philosopher; Ibsen, the Schoolman as dramatist."

This is giving a new twist to one of Wilde's most famous aphorisms in The Importance of Being Earnest. Algernon is speaking of his servant: "Lane's views on marriage seem somewhat lax. Really, if the lower orders don't set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them? They seem, as a class, to have absolutely no sense of moral responsibility."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEight Graduates of Dartmouth Who Were First College Presidents

June 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

June 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

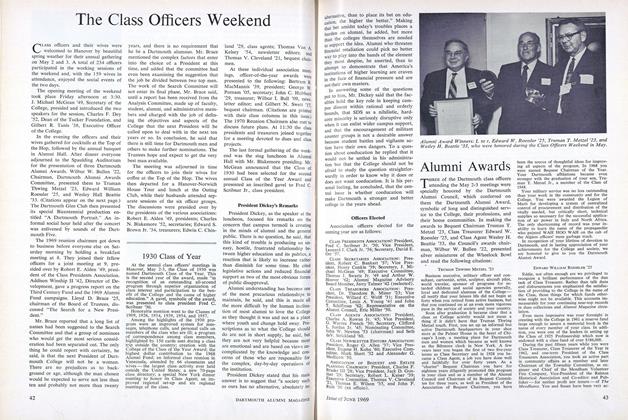

FeatureThe Class Officers Weekend

June 1969 -

Feature

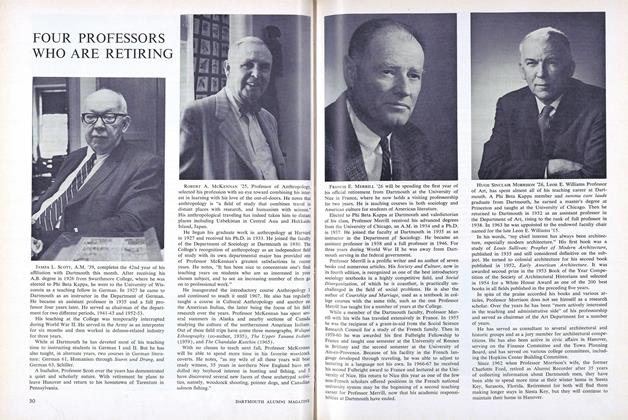

FeatureFOUR PROFESSORS WHO ARE RETIRING

June 1969 -

Feature

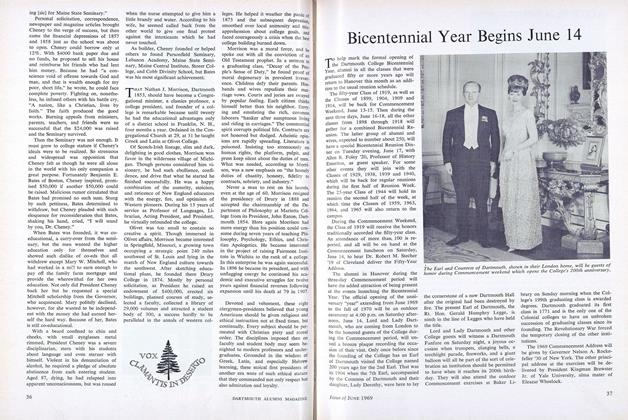

FeatureBicentennial Year Begins June 14

June 1969 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Awards

June 1969

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

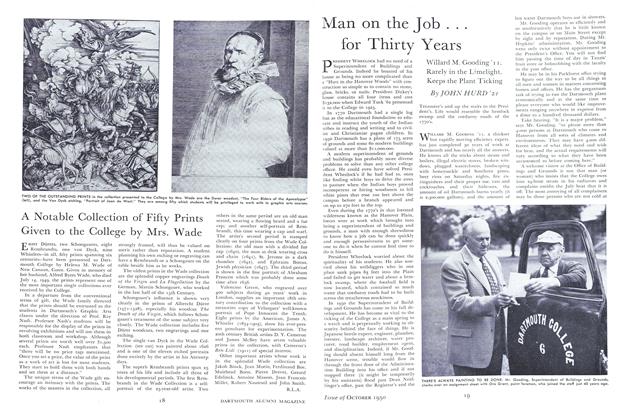

ArticleMan on the Job . . . for Thirty Years

October 1950 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALEXANDER POPE. ELOISA TO ABELARD WITH THE LETTERS OF HELOISE TO ABELARD IN THE VERSION

MAY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE BULLS AND THE BEARS: HOW THE STOCK EXCHANGE WORKS.

DECEMBER 1967 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksEGYPTIAN ASTRONOMICAL TEXTS: III DECANS, PLANETS, CONSTELLATIONS AND ZODIACS

JUNE 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

OCTOBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN AUSTRIA WITH MUNICH AND THE BA VARIAN ALPS.

APRIL 1972 By JOHN HURD '21

Books

-

Books

BooksPLASMAS – LABORATORY AND COSMIC

MAY 1966 By AGNAR PYTTE -

Books

BooksTHE INTERNATIONAL COURT

October 1932 By D. L. S. -

Books

BooksUnmet Hope

MAY 1978 By DAVID DAWLEY '63 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March, 1924 By David Lambuth -

Books

BooksANY OLD WAY YOU CHOOSE IT: Rock and Other Pop Music, 1967-1973

March 1974 By J. MICHAEL STUART '71 -

Books

BooksAMERICA'S VIETNAM POLICY: THE STRATEGY OF DECEPTION.

APRIL 1967 By PAUL LEARY