THE LIBERALIZATION OF AMERICAN PROTESTANTISM: A CASE IN COMPLEX ORGANIZATIONS.

MAY 1973 RONALD M. GREENTHE LIBERALIZATION OF AMERICAN PROTESTANTISM: A CASE IN COMPLEX ORGANIZATIONS. RONALD M. GREEN MAY 1973

By HenryJ. Pratt '56. Detroit: Wayne State UniversityPress, 1972. 303 pp. $15.95

During the early 1960s the National Council of Churches opened a new phase in its career. Departing from its moderate political stance of the 19505, the Council began a period of active social and political reformism that carried its influence into the towns of the Mississippi Delta and legislative hearing rooms in Washington. The question posed at the beginning of Mr. Pratt's study is why this change should have taken place. Why did a large federated interest group, whose normal tendency should have been the maintenance of the status quo, make the shift from a moderate to activist stance?

To answer this question Mr. Pratt takes the reader on a thoroughly researched and sometimes fascinating journey over the route followed by the Council from its formation in 1950. Moments of crisis are used to illuminate the Council's workings. Thus, a chapter devoted to the National Lay Committee Controversy of the early 1950s helps to explain the relative impotence of business-oriented and religiously conservative groups in the Council's affairs. Despite a strong conservative challenge led by millionaire J. Howard Pew, moderate and liberal bureaucrats prevailed in this controversy, partly because the Council's funding through large and impersonal denominational bodies served to insulate the leadership from the pressures exerted by individual wealthy donors. Indeed, again and again, Pratt's analysis makes clear that the very remoteness of the Council's bureaucracy from the day-to-day pressures of a conservative laity helped facilitate the Council's turn to activism.

In addition to this bureaucratic independence. Pratt offers other reasons for the shift undergone by the Council. These include the increasing influence of liberal seminary graduates within the Council, the urgency of public events (especially in the South, where the Council had little denominational support and hence little reason for caution), and the growing tendency during this period toward the employment of legislative remedies for social evils. Basic is the strong Social Gospel orientation inherited by the National Council from its predecessor, the Federal Council of Churches. Indeed, when measured against this longer activist tradition, one might strongly argue — as Mr. Pratt does not — that the liberalization of the early 1960s primarily represents a reemergence of a reformist stance prudential; relaxed by the National Council during the decade of its existence. If this is so, then it may be that a better title for this book would have been The Re-liberalization of American Protestantism But that is a minor point of emphasis. As it stands. Pratt's work is a solid and fascinating contribution to our understanding of a major "Vicious and moral interest group during a period of national crisis and reform.

A member of the Department of Religion,Dartmouth College, Mr. Green teaches threecourses: Religion and Society in America;Theological Ethics: Sexuality and Society: andTheological Ethics: Christian Economic andPolitical Thought, and he also conducts a seminaron Comparative Religious Ethics.

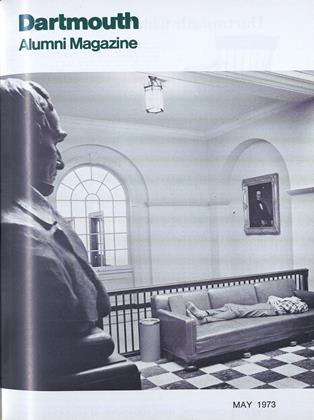

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat's So New About It?

May 1973 By Joanna Sternick, A.M. '72 -

Feature

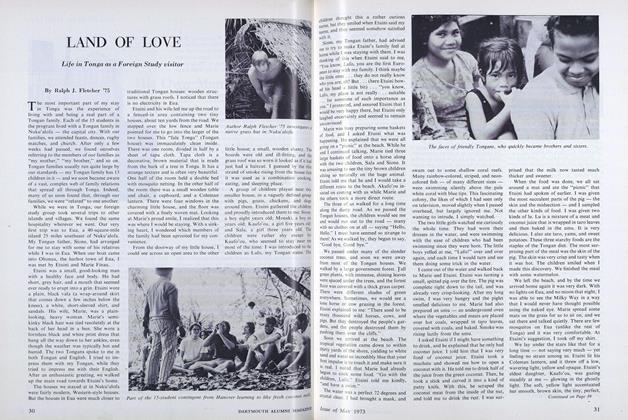

FeatureLAND OF LOVE

May 1973 By Ralph J. Fletcher '75 -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

May 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Yell Revisited

May 1973 By Russell O. Ayers '29 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

May 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleHis Own Man

May 1973 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35

RONALD M. GREEN

Books

-

Books

BooksINTERVIEWS WITH ROBERT FROST.

NOVEMBER 1966 By C.E.W. -

Books

BooksDOWN THE DORDOGNE

June 1933 By D. E. Cobleigh -

Books

BooksAN ADVENTURE IN TEXTBOOKS.

MARCH 1970 By DENNIS A. DINAN '61 -

Books

BooksTHE NORMAL CEREBRAL ANGIOGRAM,

January 1952 By HENRY L. HEYL, M.D -

Books

BooksIN CLEAN HAY.

January 1954 By MAUDE D. FRENCH -

Books

BooksPRINCIPLES OF MONEY AND BANKING

May 1938 By Ray V. Leffler