Double Trouble?

Like it or not, the cloning of humans is going to happen. An ethicist weighs the consequences.

May/June 2001 Ronald M. GreenLike it or not, the cloning of humans is going to happen. An ethicist weighs the consequences.

May/June 2001 Ronald M. GreenLike it or not, the cloning of humans is going to happen. An ethicist weighs the consequences.

I BELIEVE THAT WITHIN FIVE OR 10 years, researchers will produce a baby by means of cloning. If the child appears reasonably normal, cloning will become a regular occurrence.

Since Dolly the sheep was cloned in February 1997, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) cloning has been accomplished in a host of mammals, including cows, pigs and monkeys. It involves taking a body cell from one individual and injecting it into the enucleated egg of another.

A handful of states prohibit efforts to clone humans, though no federal law stands in the way of the research.The principal obstacles to cloning a human are logistical and ethical. The researcher would need a large supply of viable human eggs (277 sheep eggS were needed to produce Dolly) and some female volunteers willing to carry cloned embryos to term. Both mother and child would face unknown psychological and physical risks.

Let's assume, for the moment, that the process of cloning becomes sufficiently well developed to impose no greater physiological risks on the children produced by it than by in-vitro fertilization or other reproductive technologies. Are there issues we need to worry about?

As early as 1932, Aldous Huxley's .Brave New World presented a disturbing vision of a stratified society of specialized clones. Huxley's Alphas, Betas, Gammas, Deltas and Epsilons may have been programmed to be happy with their determined social roles, but the society he depicted, with its absence of freedom or individuality, was a nightmare. Would cloning technology lead to such a society? Perhaps. But if this happens, I suspect the problem will not be cloning but the political decisions behind it. Let's not forget that only half a century ago, without any special reproductive technology, the Nazis imposed a horrifying eugenics policy on millions of people. The lesson here is that we don't need to ban cloning; we need to preserve democratic institutions and values to prevent misuse of the science.

Another fear is that some people might try to produce clones for use solely as organ donors or for other forms of servitude. But I don't think there is reason to think that the advent of cloning technology would induce us to change the laws that already protect children from physical exploitation and abuse.

Some worry that people will want their children to be clones of Brad Pitt or Cindy Crawford, leading to commercially available genotypes and a dangerous loss of genetic diversity. But I believe only a small number of people who cannot otherwise have a biologically related child will turn to cloning, because most people want their children to be like them. That means most of us will keep on producing children by old-fashioned sex.

Some people see a threat to the basic freedom of a cloned individual. Nearly 30 years ago, the philosopher Hans Jonas feared that a child born with a parent's or celebrity's genome will be fated to live in that persons shadow. This led Jonas to enunciate a new human right: the right to ignorance about the meaning of one's genetic constitution. It is a moral requirement, Jonas said, that we "respect the right of every human being to find its own path and to be surprised by itself."

At one time, I was strongly persuaded by Jonas's argument. But then I learned more about genetics. Although genes play an important role in shaping our physical and temperamental features, they are only one factor in a complex process. The molecular biologist Richard Lewontin warns us against "the fallacy of genetic determinism." From birth to death, he reminds us, each organism undergoes "a development that is a unique consequence of the interaction of the genes in their cells, the temporal sequence of environments through which the organisms pass, and random cellular processes. As a result, even the fingerprints of identical twins are not identical."

Since we are not just our genes, it is a mistake to believe that an individual who inherits another persons genotype will be fated to re-live that persons life. A clone of Albert Einstein might find physics boring and be attracted instead to music or journalism. A child produced from the cell of a parent or grandparent might easily chart her own course in a rapidly changing world. True, such a child might face the unrealistic and unfair expectations of those who cloned her. But the problem here is the unwarranted expectations, not cloning. Anyone embarking on reproductive cloning should undergo counseling and preparation to avoid such problems.

Though cloning is not something we need to stay up worrying about at night, it is still reasonable to ask why we need to move in this direction at all. Is it worth opening the lid on this possible Pandoras box merely to help some infertile people have a biologically related child?

In answering this question, we should bear in mind that at the heart of SCNT cloning technology lies the quest to understand how differentiated body cells can revert to their "embryonic totipotency"their early ability to become any cell in the body. Once this process is understood, it maybe possible to take a body cell from an individual and reprogram it to produce immunologically compatible cell lines and tissues. The road to cures for various diseases, from diabetes to Parkinsons to cancer, passes through cloning research.

Several biotechnology companies are racing to develop this cloning-based, cellreplacement technology. Greater understanding of cloning itself—and movement toward cloning a human—will be byproducts. We can try to avoid any steps toward cloning by banning the basic research. But this would deprive society of many benefits. We can also try to ban any cloning aimed at producing a child. Unfortunately, if and when the safety factors are better understood and cloning appears to be reasonably safe, many people would bypass a ban in their efforts to have a child.

My own preference is to let scientific research run its course. Instead of trying to ban cloning, we should work to ensure that scientists and clinicians respect the strictest standards of human-subjects research. Like it or not, the cloning of humans is in our future. Let's strive to make it a humane addition to medical technology.

Religion professor RONALD M. GREEN, director of Dartmouth's Ethics Institute, hasserved as an ethics consultant to the NationalInstitutes of Health and in the biotech industry.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

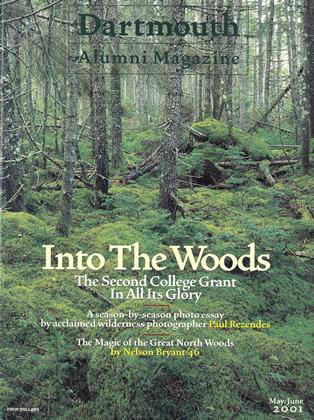

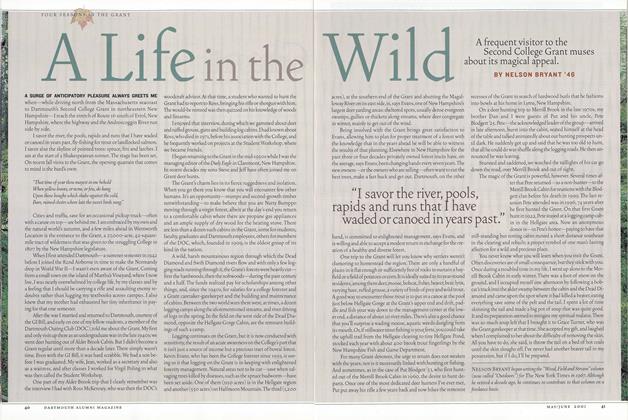

FeatureA Life in the Wild

May | June 2001 By NELSON BRYANT ’46 -

Feature

FeatureShooting the Grant

May | June 2001 By BEN YEOMANS -

Feature

FeatureVoices in the Wilderness

May | June 2001 By Jennifer Kay '01 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GREAT NORTH WOODS

May | June 2001 By Michelle Chin '03 -

Cover Story

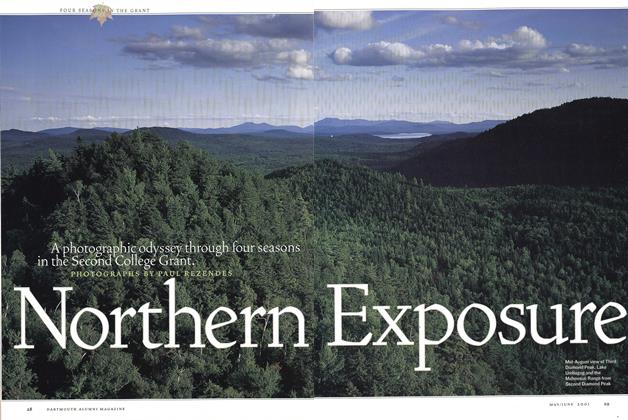

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May | June 2001 -

Sports

SportsThe Sporting Life

May | June 2001 By Lily Maclean ’01

Ronald M. Green

Faculty Opinion

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONInvestor’s Ed

Nov/Dec 2006 By Annamaria Lusardi and Alberto Alesina -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTo Be a Lazy European

Jan/Feb 2007 By Bruce Sacerdote ’90 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Well-Traveled Story

July/Aug 2009 By Ernest Hebert -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionPatriotism’s Perils

Jan/Feb 2003 By JAMES BERNARD MURPHY -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Sorry State of Affairs

Jan/Feb 2008 By Jennifer Lind -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July/August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton