IN the summer of 1969, some 15 people tented a house together in Hartland, Vermont. It was a loose group of Dartmouth people and their friends and lovers, who had some vaguely, formulated ideas about living together and being politically active. Over the winter, a nucleus of six people emerged from the group intent on making a life together. They borrowed money and bought a dilapidated farm deep in the woods of Canaan, New Hampshire. By April of 1970, seven people - two women, four men, and a newborn infant - had moved "onto the land" and set about the complex business of communal living. They called themselves the Wooden Shoe, and - for a time - they prospered.

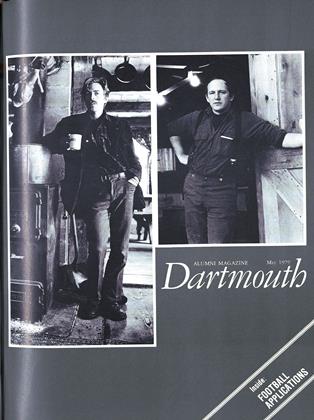

Other people came and went as visitors or organic farming-apprentices; a couple of the original members left and were replaced by other deeply committed people; and then, around 1976, it fell apart - dwindled to a commercial partnership of two. Today, Jake Guest (one of the original seven) and Peter Howard (a young farming apprentice, recently arrived) work the place as a truck farm. Their partnership is not a long-term arrangement. It has no particular future. In fact, they, too, have begun to talk about splitting up.

What, then, was the meaning, if there was one, of the Wooden Shoe? Was it a failure, a naive rebellion against the natural order of things? Those (and they are many) who are upset by the idea of communal living would probably say it was. I sought out some of the scattered communards to ask them what it had meant to them. They haven't scattered very far. Most are still in Canaan. They talked about the Wooden Shoe willingly, easily, with great feeling. Only in the most superficial sense of the word, they said, could the Wooden Shoe be called a failure.

Jake Guest '66 left Dartmouth in 1963 tojoin the United States Army. After fouryears of military service - three as anenlisted man - he returned, to a campuspoliticized.

Jake Guest:

The Wooden Shoe came out of SDS at Dartmouth in 1969. SDS was the most democratic organization I have ever been involved in. People would get together in a group and make decisions by consensus, very methodically by consensus. They would spend hours and hours hammering out a consensus, trying to accommodate all the different ideas. It was the first time many of us had participated in a really democratic process, or dealt with scary and important decisions, such as defying the law.

The whole antiwar thing had started to heat up. All of us began to realize that this damned war had permeated everything, including Dartmouth. There was strong sentiment about Dartmouth's ROTC. The rap was, you know, that ROTC should be part of a liberal education because the military is part of the whole culture, blah, blah, blah. And we were saying that ROTC was training officers to go to Vietnam not only to kill Vietnamese people in a ridiculous war, but also to exploit enlisted personnel - mostly blacks, Chicanos, and poor whites - in the U.S. Army. That bothered me as much as the war itself. It was genocide. And that was wrong, you know? Several attempts to get ROTC kicked out were unsuccessful, and finally we decided - again by consensus - to occupy the administration building, Parkhurst. Which we did - on whatever date it was in the spring of 1969.

It was a highly charged emotional experience. We knew that they would probably put us in jail and God knows what else. There was the possibility that we would get beat up. We had decided not to resist forcibly. They came in and read an injunction and left, and all during the evening and through the night, tension increased. We kept hearing reports of national guard and state police, and there were thousands of people outside, and we were scared. But we all felt really close, you know?

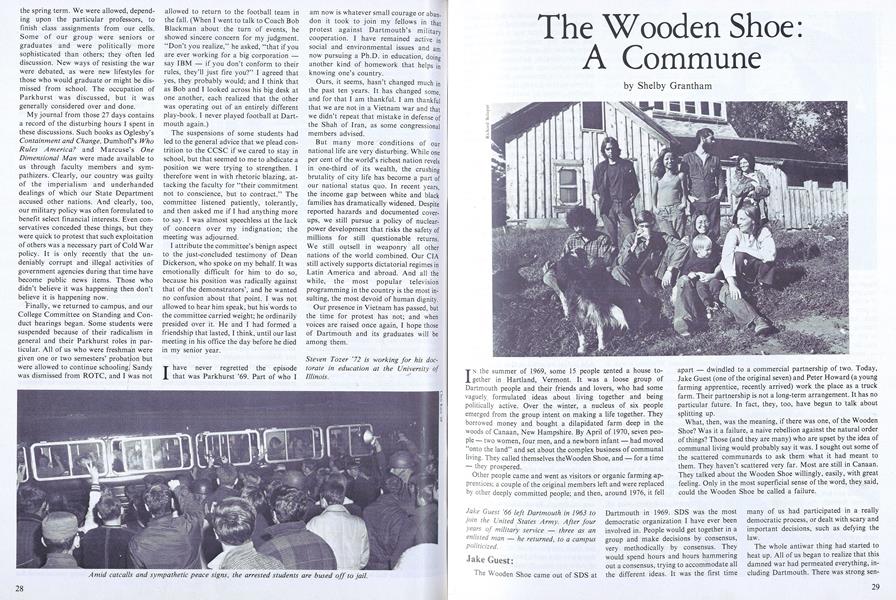

At 3:00 a.m., they came and arrested us all - 56 of us. Then they brought us to trial, and they put us in jail for 30 days. After we got out of jail, the direction of life for some of us seemed to have changed. We floated around Hanover full of desire to go on and trying to figure out what to do next. Finally, we rented a house in Hartland, Vermont, eight or nine of us, mostly Dartmouth people. And we had this great idea that we were going to have this house in the country and do political work in the city somewheres. I dunno. Whatever it was. It didn't take long before we realized that we were not, in fact, carrying out any political activity. It was too much work just living with a group of people. For several of us the focus changed. The word ecology started getting kicked around a lot, and there were collectives and communes starting up all over, especially in Vermont. Some of them were political, a few were spiritual. Most were just kind of a cultural reaction, an attempt to do something different, to live in a way which was more harmonious with each other and with our environment, both physical and economic.

People came and left at Hartland, and Carol was pregnant, and there were all sorts of traumatic ups and downs. Collectivizing the situation was a process. For a long time Carol and I did a lot of the cooking. And Carol, especially, played out a housekeeping and cleaning and cooking role, a female role, which fairly rapidly broke down. We started talking more and more about what this was, to try to live together, and we realized that things had to be taken care of, things had to be cleaned and eventually there was a dissolution of sex roles. We broke down our finances more and more, until everybody was putting everything in. And through collective decision-making, we allocated money where it was necessary. And it was an adventure, trying to do that, trying to live together, trying to make those decisions together.

We really were poor, and in an attempt to get money, I started this thing called the Wooden Shoe Labor Force. The name Wooden Shoe came From a printing press, the SDS press, which somehow got into the basement of the Hartland house. It was called the Wooden Shoe Press, because of the old story about the word sabotage. French workers once threw their wooden shoes into the machinery during a labor uprising. The shoes were called sabots, and from that is supposed to have come the word sabotage. The press was supposed to be a political press, although we never got it together to print anything on it. The Wooden Shoe Labor Force was simply our collective labor applied to whatever anybody wanted done. We sorted and planted tulip bulbs, we tore down buildings, did gardening, snow-shoveling, roof-shoveling, leaf-raking, painting. We did a lot of painting. And people began to know who we were. "Oh, yeah - you're the Wooden Shoe!" And everybody liked that name, so it kind of stuck.

In the winter of 1970, we started looking for land. We looked at this place and got really enthusiastic. We could overcome anything, you know - that was the idea. And in fact we could at that time. We all had both a personal and a collective resiliency and could put up with anything. I mean, this place is not much now, but it's a lot better than it was.

A whole bunch of us moved out to this ratty old house, jacked it up, and started fixing it up. We didn't know anything about growing anything, never had a garden before, didn't know what we were doing. A neighbqr came out and put some cowshit on it for us and showed us how to plant things. Most of the local people were pretty freaked out, though, because a hippie commune was coming to their town. They didn't do anything except bad-mouth us a lot, though. People who met us usually liked us. We made an extra effort to be nice, and we were mostly well-educated and could pull class rank on people. A few people came up looking to make trouble, but there were a lot of us, and nobody dared give us a really hard time. The chief of police was pleasant, and we got tight with him right off the bat. We were no dummies.

We carried with us a commitment to consensus, and we had a meeting once a week. Took all day, all goddamned day. We talked about money, and plans, and building - the mechanics. We made a collective decision to raise two children born here. We decided that all our money would go into a common fund, and ten per cent would come right off the top of it for medical needs - everything from toothbrushes to major surgery. And we scheduled things. Chores were assigned by the day, and animal care by the week. We also agreed that nobody would get a regular job, because a regular job meant you wouldn't be cooking and taking care of the kids on a fair number of days.

Parenthood is really time-consuming, and it's hard work, and it seemed to make sense to raise the kids collectively. Instead of being exposed to the whims and personalities of just one or two people, they would have a lot of input and a lot of love from a lot of different people. It worked. Yeah, I really think it did. And it gave a lot of us who otherwise wouldn't have had the opportunity a chance to learn how to do all that stuff. Learn how to change diapers. Learn what it is to get up with kids, and convince them to get dressed, and feed them, and worry about their medicine and their runny noses and sore toes, and get them to play with other kids. It was fun. It wasn't a chore. I mean, I've got a kid now.

And people got a chance to interact very intimately. Originally, there were no doors in the house. You were very aware of other peoples' personal relationships. We even argued in public.

In eight years, we only had to tell about three people to leave. There were a couple of crazies. A guy came up once in a suit and tie and no shoes and said he was a warrior for St. Jude, for the liberation of mental patients. And a young kid came and ripped us off once. There were a couple of evangelically inspired types. But most people who didn't fit just left. We got very good at putting peer pressure on people. We just looked through them, and after a while they couldn't take it any-more.

But finally, as we got older, we began to wonder about whether we wanted to be poor for a long time. Some of us wanted more control over our own farms. Some were very stubborn about what we were doing here - me more than anybody else. Some wanted more intimacy with another person.

It isn't right to call it a failure. Things didn't seem to work at the intense level we tried them at. It didn't work as a commune in the context of this particular time and particular culture. Economically it did work. We supported a lot of people on very little money. And it did work for raising children. It was a valuable experience. Especially the childcare.

Ed Levin '69 majored in philosophy andmathematics at Dartmouth and studiedchemistry and physics and art as well. Hebegan learning how to build with largetimbers when he was at the Wooden Shoe,and now he makes custom-built frames forowners or contractors who want housesframed in the old way, with mortises andtenons and pegs. In the winter he writes.

Ed Levin:

It's easy for me to answer a lot of mechanical efficient-cause questions about how the Wooden Shoe started. The whys are really hard. It was post spring of 1969 and all that means, in terms of radical politics and the war and the machine. I wasn't looking to spend another summer in Boston, where I grew up. I liked it up here. Jake Guest needed a place to live, so we started looking for one. We had a variety of loose commitments from other people, too, and finally we found a house in Hartland, Vermont. By the winter of that year, some of us had decided we wanted to live together and buy some land. Finally we found a place in Canaan - quite a ways out, slightly neglected, slightly scruffy farmland. But in a very beautiful place.

During that first year together in Canaan, we fixed up, to some extent, the old house. It was an original 1790s building, very dilapidated. It was rundown, dark, dirty. But the frame was beautiful; it was exquisitely made. There was no electricity there and no telephone. It's a long way from the nearest wires, and it would have cost a lot of money to bring in electricity. We didn't have anyone who wanted it. There was a well, a pretty good well. We dug a pipe so it gravity-fed into the basement, and then we hand-pumped the water up into the sink. We had an outhouse - not a whole lot of house, mostly just out.

The following year we built a barn. It was my first building experience and probably everybody else's. We hauled poles out of the woods and built a full barn 26 feet by 40 feet and spent something like $700 - and that included a $300 roof. You can't build a shack for that now. That was a wonderful building. Later, unfortunately, it burned. The year after we built the barn, we started adding onto the house.

The Wooden Shoe was an incredible experience for me. Just learning to cooperate was transforming. I don't want to make any claims of great personal strides, but I changed. I had to become less self- centered. I had to consider the repercussions that things I did would have on a lot of other people. I played a certain number of typical male roles, but also a lot of roles that are usually assigned to women - childcare, cooking. We'd meet once a week, to make collective decisions for the week about all the normal functionings of a household, divided among ten or twelve people. And we would also deal with personal problems and personal things that weren't problems. They weren't always pleasant, the meetings. They were sometimes very tense. But they are one of my warmest memories.

One very important thing I got out of the experience was an ability to suspend judgment. I learned that if someone isn't actually stepping on your head, you can say, okay, that's your way and this is my way, and refrain as much as possible from making qualitative comparisons. I see that as a real value, that enhancing of tolerance.

Sex? Yes, sex is always the question people ask about communes. Our motivation wasn't sexual. We were half single men and half couples when I was there. I wasn't only single, I was celibate. Sometimes by choice and sometimes not by choice. "What do they do out there?" is the other question. We sat, talked. Occasionally we went to the movies. Same things I do for entertainment now. We had parties. Oh, yeah. There was Bottling Night. Lord, you've called up a memory. What a night. We had made nine full hogsheads of cider at Ogden's mill in the fall, and Jim Rubens had saved wine bottles from the recycling plant - a thousand of them. And I have memories from Bottling Night of being up on the roof with several vintages of our Old Apple Blend, getting - uh - soused.

The high points were very high. One of them was children. During that time I attended the births of two kids. Anyone who has never watched a human being born has missed something. Helping to raise them was also a high, though there was always that tension between the biological parents and everybody else. I never really resolved that one. As much as I told myself that we were all sharing the parenting, it was never something I really deep down believed. I knew that it wasn't impossible that we would all stay together; but if we didn't, everything would fall out so the kids went with their biological parents.

I was only there for two or three years. I left because it did seem that we were lacking in direction. I had digested and absorbed a lot of the good things there were in that kind of a family, and we weren't growing the way I wanted us to grow - mechanically and economically. I was a carpenter and a builder living in an agricultural community. And so I left, headed off in another direction, taught myself to hew timbers and to frame buildings in the old style.

I still feel a certain closeness to those- people. But the old ways are pretty strong. Most of us are now living in pretty typical arrangements - married, with children. Some of us are not married, but our arrangements are still typical. There are some differences, some holdovers. Anita and I have our own Sunday meetings, for instance. We see each other seldom enough during certain parts of our life, especially when I'm very busy in the warm weather, that we felt the need to make a space to be together and arrange our time. And clean house - literally and figuratively. So that's what we do. And in most of the arrangements, too, the roles are not divided the way they usually are between men and women.

I ask myself questions like these every now and again. I'm sitting, and I have a reverie, and I realize that I can't give as many of the answers as I'd like to. I know that things worked out fairly well in the end. Right now, I'm having waves of nostalgia. Some of those high points are visual images for me. They balloon in the summer. People going about their tasks, and animals, and children - you know, idylls. I grew up in the city. I didn't know anything about animals. Living with other creatures, that was sort of broadening - learning to speak sheep and pig and dog. I became a reformed intellectual. I worked with my body. It's taken 20 years of schooling and four or five of physical labor to effect some kind of synthesis, where I can now seem to manage to do both.

Bruce Pacht '67 was the chronicler of theWooden Shoe, the loss of whose journals inthe barn fire everyone regrets. Pacht nowworks with the retarded and mentally handicapped in Lebanon, New Hampshire.

Bruce Pacht:

I need to remember the Wooden Shoe as a personal history. I graduated cum laude in French in 1968 and then took an NDEA graduate fellowship in French at Stanford. I wanted to become a professor. I always wanted that, always.

At Stanford, I began to be bothered by the political situation. I did not want to be drafted and sent to Vietnam - I did not want to be killed. I think I would have been willing to die for some kind of principle, but there was no principle involved. The war was all based on money and hegemony and political bullshit, and I didn't want to die for that. I liked to think that there was something I would die for. But not that.

I was studying French ten hours a day, doing the kind of obsessive job I usually do. There was a lot of political activity at Stanford, and I faced a decision. Being into French all day every day meant forgetting about the political situation, the war, the poor people. Those were the only two paths I saw. I stay in French, or I get out. So I left.

I came back to Hanover for Green Key weekend, looking for classmates who might be in the same perplexed state of mind I was in. I arrived Tuesday night and slept at my fraternity. The next day, I wrote a lot in my journal and then walked over to the French Department at about 2:45. The Five Colleges Book Sale was going on, and they were playing softball on the Green. There was a commotion at Parkhurst. I walked over and Dave Green came to the door and said, "We're gonna lock the doors at three o'clock. This is an occupation." I'm standing there still scribbling in my journal, and Dave says the doors are going to lock. I said, terrific, this is great, this is the first time I have found somebody doing something, something concrete. I have to be part of this. So I went in. That was the first real commune - Parkhurst. Fifty-six people making communal decisions about their fate.

We spent 30 days in jail, all over the state of New Hampshire, for that. And jail was the second commune. Fourteen of us were in the Rockingham County Jail together, most of us on the same tier, two to a cell nine by seven by six. It was there that the idea of living together when we got out began being talked about. There was an aimless couple of weeks after we got out, and then somebody said, "Look, why don t we get a house together?" I was restless,, though. I wanted to see my parents. So I said, "Look, here's 40 bucks. If you ever do rent a house, here's my rent. And I left, after a party one night.

Carol Stomberg had been going with Ed Levin on and off for years, but there were tensions between them. The night I left Hanover, I asked Carol if she wanted a lift home to Boston. She said okay. When we got to the Mass Pike, I said, "I'd like to take you home with me to New York." She said okay. We got to New York, and I walked in the door with this goyishe Amazon wearing cutoff jeans stitched up the side with rawhide, all the way up to the belt. And my mother ran to the bathroom and puked. That was the beginning of Carol and me.

She became pregnant, and we weren't ready to be pregnant, so we decided to go to Poland and get an abortion. We drove up to Hanover to say goodbye. We had a party and then went over to the courtyard of the Hopkins Center snackbar and lay on the ground, four or five of us, looking up at the sky. And I said to myself, now what the hell am I doing? I'm going to Poland and get an abortion, and Carol is going to come out, and I'll be standing there in Gebrovnichsville with this woman who's just had her uterus scraped out, and what the hell is the next step? On the other hand, I have a chance to do something here, to build something. So I turned to her, and I said, "Let's have the kid." And she said okay. We all got into cars and drove down to the Hartland house that had been rented. Jake opened the door, and I said, "We're going to stay."

Right from the start, the sexual agreement was that two consenting adults could do whatever they wanted with each other. That was the verbal trip, anyway. There was still a lot of emotional stuff locked up. And eventually we had a meeting where we decided 100 per cent on a common fund. We found a place in Canaan and bought it. We borrowed $1,000 from Dartmouth professor Andrew Lety for a down payment, and Kate and Bob Guest - Jake's parents - lent us the other $9,000 on a personal note to Jake.

Before we actually moved, Carol gave birth to Jesse. Jesse's birth was one of the key elements in the formation of the Wooden Shoe. We had a home birth with Dr. Putnam, and about 20 people were sticking their heads through the door. It was terrific, everything was wonderful, no complications. And I arranged a Jewish ritual circumcision. There were about 30 people in the room for the ceremony - my parents, all our friends, the people from the Wooden Shoe, and Doctor Putnam, who was going to do the cutting. And one of the Wooden Shoe people, Rob Nichols, said, "Wait." Fact magazine had just come out with a cover picture of a screaming baby and the caption, "Is circumcision really necessary?" Rob had seen it and said, "I don't think we should do this." Thereupon ensued an hour-long discussion, wherein each person was allowed to speak. The only two others in favor of circumcision were the doctor and my father. I knew I could say, it's my kid, it's my tradition, I want to have it. Had I done that, I think I would have set up a negative feeling that the Wooden Shoe would never have recovered from - a non-communal decision which would have doomed it at the outset. We called off the circumcision.

I feel like I had the power then to make it or break it. I think others at other times, with other decisions, did the same thing. That level of sacrifice has to be made for a commune to work. You have to make your own tribe, because you are an artificial tribe. Communal childcare was another sacrifice Carol and I made - allowing other people to handle Jesse's body, on the lowest level. And also submitting to communal decision things like whether he went home for Christmas to Carol's parents.

Carol and Jesse and I left in 1975 and moved to a place of our own in Canaan. The Wooden Shoe land was finally taken out of Jake's name and is now owned by a trust comprised of seven people - the core group of Wooden Shoe people. In 1976, Carol ran for the New Hampshire General Court and decided we should get married. "If people ask me whether I'm married," she said, "I don't want to say, well it's like this. ..." So one Saturday we went to the town clerk and got married. We're expecting our second child now, and Carol is looking forward to spending a lot more time with Jesse.

Jim Rubens '72 has established a largescale tree service in the Upper Valley. Henow lives in White River Junction, Vermont, although he has hopes soon of buying land in Hanover.

Jim Rubens:

I finished my Dartmouth education in 1971, about the time the Wooden Show was coming together in its final form. I knew people there and our life styles and beliefs crossed. The Wooden Shoe was an effort to develop a microcosm - it was really an abandonment of the effort to change this decaying society in ways we thought necessary, because changing the whole society was a large task fraught mostly with failure.

I moved to the Wooden Shoe in 1973. At that time it was very good, very stable. There was a lot of commitment there. I knew that if I put energy into it, it wouldn't be wasted. We wanted to build a community where people were equal. We tried to share everything - the cooking, the child-rearing. The goal was that everybody would participate equally in everything. We made a very conscious effort to restructure the division of labor by sex. We policed ourselves continuously. We'd talk in meetings about how there weren't enough women doing the building. That particular thing we weren't able to bring to reality, for two reasons: Ed wanted his domain, wanted to do things his own way, and I wanted to do things my own way. And some of the women didn't want to build.

Certain people were very tied to doing their own things. Ed did at least half of the building. Bruce was very much into getting money from outside. These were - hard for us to deal with. It was against the ideology we tried to maintain. We tried - not too successfully - to eradicate those differences between us, in an effort to up- hold the building of the community tie we wanted, which we wanted to submit ourselves to.

We tried to live very ecologically. We shat in shitpits. That was a lodestone. The shitpit filled, it was composted, and after a year or two, when it was composted enough to be safe, it went back to the land and grew food. Our diet was homegrown as much as possible. We had our own milk cow, grew all our own vegetables. We kept a root cellar packed full of enormous amounts of just about everything we needed, with the exception of grains, certain condiments, and soap powder. We were even beginning to try to grow grain. I was a vegetarian, but others were not. We raised our own pigs and did our own slaughtering.

It took two years for me to decide that it wasn't working. It wasn't realistic because it didn't take into account enough the differences between people. That was my own reason for leaving. It was valuable for me despite its failure. My own past history was one of being very cut off from people. The interaction between people was incredible at the Wooden Shoe, and that was very valuable for me.

Anne Brooks graduated from college in upstate New York and then came to hergrandparents' rustic cabin in Woodstock,Vermont, to think in solitude about whatto do next. The local cooperative movement and its concern with social welfareappealed to her. She joined it, and it led herto the Wooden Shoe.

Anne Brooks:

The first commune I was in was in Strafford, Vermont. A bunch of us who were working with a regional bulk-buying natural foods cooperative rented a house together there in the fall of 1971. It wasn't very organized. Some of us tried hard to set up communal agreements, but others were really fighting any agreements at all. In the summer, when the lease ran out, it dissolved, and about that time I began to visit my friends at the Wooden Shoe a lot.

I found out that the Wooden Shoe was a real community. They had taken the big step and bought land. And there was an identifiable feeling about being there, a tribal family feeling. That felt good. I decided to stay there for six months - which turned into four and a half years.

Working things out with a lot of people was a struggle. Think about working something out in a couple relationship, and then multiply that by seven, and up to fifteen, and you can see how complicated it gets. But it was worth it - for the sense of support, and because the numbers made a lot of other things easier. Not only the workload, but also the relationships. A couple might start having the same pattern of fights all the time, and others of us could see that and say, "Hey, you are doing this and this, and so-and-so is always going to respond that way if you keep doing that. So you can continue to do it and so-and-so will continue to freak out - or you can find a way around it." It also happened between men and men, and women and women, and also between men and women who weren't couples.

You knew people there cared about you. Everybody was working to try to make it good for everybody and at the same time to get what they needed, too. It taught me to define what was important to me - without losing sight of the needs of the group or of other individuals. It also made me strong. Made me learn how to fight for what I wanted, really stand up for what I believed and needed.

Sex? Sex wasn't a big thing. It was very straight, for the most part. There was some experimentation, mostly very dull. People experimented with more than one relationship at a time, and came back to feeling that the primary relationship is just that. There's only so much intensity you can stand.

Most of us slept with each other, at one point or another, because we were close and intimate, and because it was allowed. But for the most part, day to day, people stuck by couples. There was a real pressure to be coupled. We fought it, because it made the people who weren't coupled feel left out, but we didn't do very well fighting it.

I did feel that the Wooden Shoe was my place, it was my home - although I resented the fact that the townspeople seemed to give the men all the credit for what we'd done with the place. They would come up and say to Jake or Bruce, "Hey, this farm looks beautiful. And I'd be standing behind them turning purple and thinking, "I did it, too!" That was especially hard because the women expended a lot of energy smoothing the emotional cockfighting of the men. Boris used to say that the Muscovy ducks we had were a perfect microcosm of the way the men dealt with each other at the Wooden Shoe: Someone was always on top and everybody else was always fighting to get on top.

When I stand on the steps at the Wooden Shoe and look out at the land, I get a really warm secure feeling. And I have wonderful memories of us as a commune. We were really a powerful group of people. We were seen as a very cohesive, dedicated, strong group, who knew what we were doing and where' we were going, had definite ideas about childcare and politics, and so forth. We did an incredible amount of education in Canaan, to open the community to "deviant" behavior.

We weren't running around naked down- town or anything, but one of the lovely things about being at the end of the road was that you could go out in the garden and take off your shirt while you worked. For a woman, of course, that is still totally unacceptable behavior. It was also deviant behavior for the women to be roofing, driving trucks, and speaking up in town meeting. But when we started doing odd jobs for people in town, and they saw we weren't just flakos but were very hardworking people, then everything was okay. We joined the fish and game club, and Bruce got on the town planning board, and Jake and I did the census one year. The town offered us the job of running the dump. We integrated ourselves into the community and became respected.

But it was a myth. When all was said and done. Because when all was said and done, the people with the kids went away with the kids. The people whose parents had money borrowed from them and bought houses. When it fell apart, it fell apart the same way any divorce falls apart - a little worse, because it was so unequal. The hardest part for me was realizing that after really falling in love with the kids, I didn't have any ties with them except what I could work out through their parents.

It was only in the death-throes that I really understood that it wasn't going to go on, and it was a shock. I guess I thought of it as a place that would be flexible enough to allow us to change our directions. That's why it didn't continue. Because it was shortsighted about that. It didn't see that some people would get tired of farming and want to be doing other things - want to be students again, or want a different standard of living, or not want to live in the one house anymore, want some more privacy.

There was a fear that anyone's moving out of the main house and creating a separate little place on the land would be divisive. And that issue never got resolved. When people changed direction, the only thing to do was to leave, and when they had made that decision, you couldn't say, wait another two years while we work something out. They had tried and tried already. In a consensus situation, you know, when you don't get agreement, you get status quo. Basically, I think it was Jake's blocking that kept the issue from being dealt with. He was afraid that Bruce and Carol would become a powerful force if they split off.

I moved out after four years. It had gotten down to being just me and Jake. We weren't a couple - we were just the ones who were left. I realized that I didn't want to farm as a career. So I started working out to make some of the outside money we always needed. But the farm apprentices who came to the Wooden Shoe in the spring resented my not being in the fields. So I moved out. But I really missed being in Canaan, and in 1977 I bought an old trailer and got permission from the Wooden Shoe trust to put it on the land. And I became the first person to have a house other than the main house. Technically, I'm still living there. But the trust is in the process of deciding to sell the land to one person - Jake, or Peter, or Bruce and Carol.

And I'm beginning to think about a place of my own. I'm still supporting myself by the skin of my teeth, and it's time I looked ahead and thought about getting what I want - a place of my own and enough money to give my parents some help if they need it. For a few years, I'm going to have to sink myself in the real business world. It's a painful decision, leaving work I like and believe in just because it doesn't pay enough. But I have to be pragmatic about it.

AMERICAN history is full of communal experiments, egalitarian attempts to transcend the biological limits of family. During the 19th century, no fewer than 72 "successful" communistic societies existed in America, each of which continued as a commune for at least 20 years. (The oldest lasted 80 years.) Two of the 72 were groups subscribing to the "Perfectionist" ideals of the Oneida Community founded by John Humphrey Noyes of Dartmouth's Class of 1830. There were also, according to Noyes' historical study American Socialisms, some 47 "failures," including the well-known Brook Farm.

It is often maintained that the communal spirit is at bottom religious, and that the successful commune is fanatically religious. But Noyes' fellow chronicler Charles Nordhoff, a more trenchant observer than most, concluded after visiting many of America's communes in 1874 that their success depended "upon another sentiment - upon a feeling of the unbearableness of the circumstances in which they find themselves." That rings truer, somehow, especially if the Wooden Shoe is a fair example. And Nordhoff might as well have been writing in the commune-studded sixties and seventies of our own century when he added, "The general feeling of modern society is blindly right at bottom: communism is a mutiny against society."

Jake Guest still farms theWooden Shoe, althoughhe is thinking these daysabout living alone withhis child and its mother— perhaps at her place,perhaps at a new place,perhaps at the WoodenShoe.

Ed Levin bought anotherpiece of land in Canaanand built on it a home,which he shares withAnita Walling, his wife.Their first child will beborn in the fall.

Bruce Pacht, Carol Stemberg, and their son Jessenow live in another homein Canaan, from whichPacht commutes to Lebanon, where he is executive director of the UpperValley Training Center.

Jim Rubens lives alonethese days. He is nowdeeply involved in beingan entrepreneur and inmaking money - inorder, he says, to havesome influence over theAmerican economic system.

Anne Brooks, who stillmaintains a trailer on theWooden Shoe land, isnow a worker-owner atNew Victoria Printers,a printing collective inLebanon, N.H.

Shelby Grantham edits and writes for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer -

Feature

FeatureA Three-story House on Bramhall Avenue

May 1979 By Douglas Andrews -

Article

ArticleHearts and Minds Study

May 1979 By TIM TAYLOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1979 By WILLIAM A. CARTER -

Article

ArticleJudicial Clerk

May 1979 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

May 1979 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureNine to Midnight (or two if hot)

March 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHigh Tech Crisis

JUNE 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFourth in a Pig's Eye

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

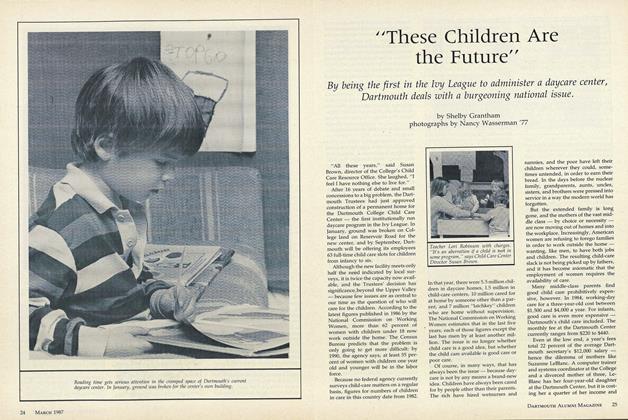

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Art Show in Boston

OCTOBER 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe Honesty That Is Dartmouth

JULY 1963 By ALAN KENNETH PALMER '63 -

Cover Story

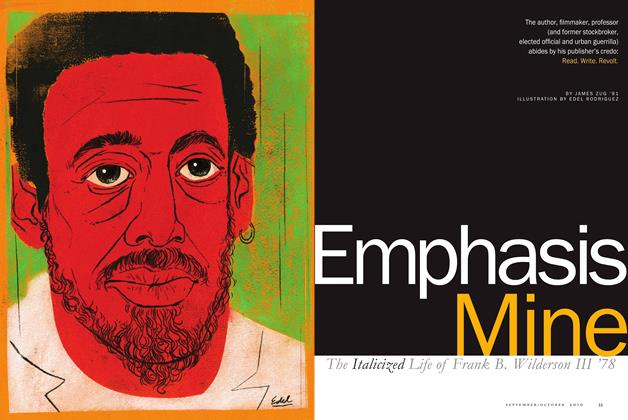

Cover StoryThe Italicized Life of Frank B. Wilderson III ’78

Sept/Oct 2010 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Feature

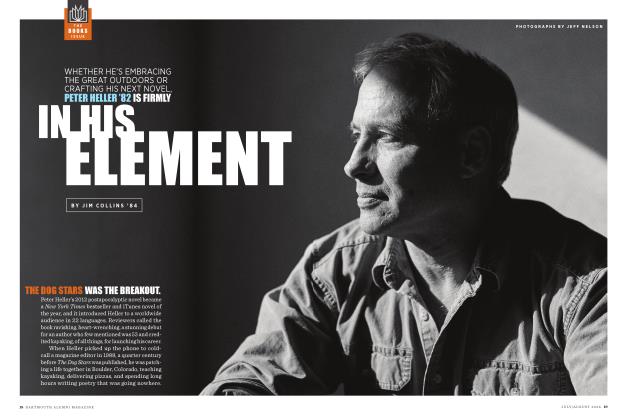

FeatureIn His Element

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA 10-STEP PROGRAM FOR GROWING BETTER EARS

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT CHRISTGAU '62, VETERAN ROCK CRITIC -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWarner Bentley's Bust

OCTOBER 1997 By Robert Nutt '49