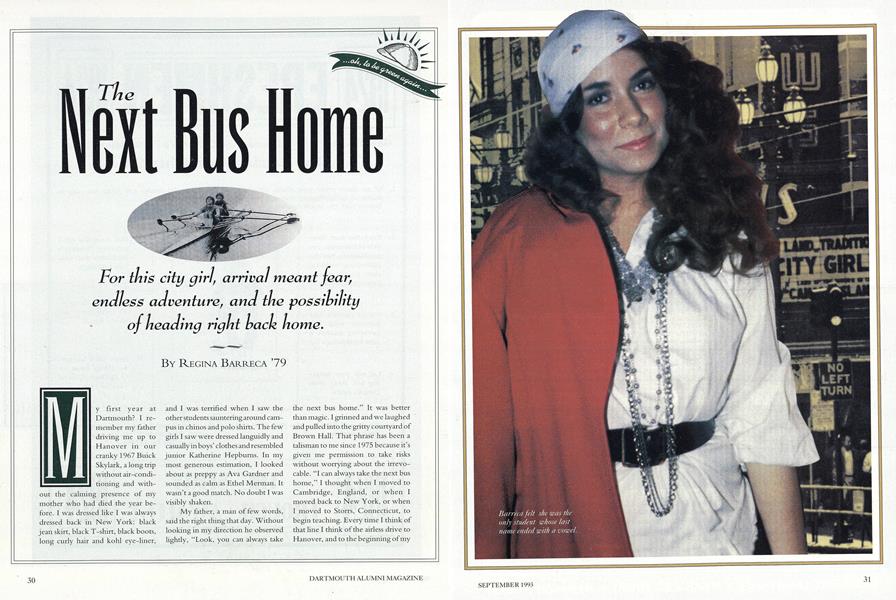

My first year at Dartmouth? I remember my father driving me up to Hanover in our cranky 1967 Buick Skylark, a long trip without air-conditioning and with and I was terrified when I saw the other students sauntering around campus in chinos and polo shirts. The few girls I saw were dressed languidly and casually in boys' clothes and resembled junior Katherine Hepburns. In my most generous estimation, I looked about as preppy as Ava Gardner and sounded as calm as Ethel Merman. It wasn't a good match. No doubt I was visibly shaken. out the calming presence of my mother who had died the year before. I was dressed like I was always dressed back in New York: black jean skirt, black T-shirt, black boots, long curly hair and kohl eye-liner,

My father, a man of few words, said the right thing that day. Without looking in my direction he observed lightly, "Look, you can always take the next bus home." It was better than magic. I grinned and we laughed and pulled into the gritty courtyard of Brown Hall. That phrase has been a talisman to me since 1975 because it's given me permission to take risks without worrying about the irrevocable. "I can always take the next bus home," I thought when I moved to Cambridge, England, or when I moved back to New York, or when I moved to Storrs, Connecticut, to begin teaching. Every time I think of that line I think of the airless drive to Hanover, and to the beginning of my life away from home. My freshman year at Dartmouth is twinned inexorably with a sense of difference, of fear, and of limitless adventure.

I needed the courage to face a place where I felt as if I were the only person whose last name ended with a vowel. I needed a sense of humor to face early fraternity parties punctuated by beery guys named Skip or Chip asking me where I went to school and then sneering when I replied, "I go to school here." It was a year before I added, "And where do you go?" which at least caught the attention of anyone who might also have trouble with the usual dating rituals. I can't imagine that freshman year is easy for anyone; surely even the suave and sophisticated among us were driven by their own insecurities and worries. (But maybe n0t...) Nothing was as hard as social life. Compared to figuring out codes of behavior, classes and exams were a piece of sweet cake. A freshman seminar may well have prevented me from reading Paradise Lost until a grievously late age, but it did provide me with a few friends I have kept until this day.

That seminar also may have contributed to my determination to teach at a public university. My professor, a man of much charm and wit, passed back first papers and flicked out the remark: "Luckily it's early enough in the term for most ofyou to find places in state colleges." He meant it to be funny. It sounded, then and now, hollow and ruthless. It is a cautionary tale I repeat to my own students as a caveat concerning their Ivy League counterparts in the workforce. "This," I tell them, "is the attitude you might encounter, and you have to know it's out there and do twice as well as anyone from a private university." I heard for the first time in 1975 an upper-division student saying, again as a half-joke, "It is not enough to succeed; others must fail." I always felt like one of those Others, and I redoubled my efforts to succeed without looking at the competition. One look back, or even one look around me, and I figured I was finished. With a blinkered vision of my own competence, I insisted on staying the course.

And believe me, it wasn't all gruel and ashes. There were great teachers, great dances, great roommates and friends, great evenings at The Bull's Eye and one infamous tea at the Inn where, unladylike as ever, I spilled Earl Grey down my one good dress. My pals, male and female alike, were also part of the dispossessed in some way. Too urban, too shy, too ethnic, too working class, too outrageous, too intellectual, too subversive to be accommodated by the mainstream, we formed our own Dartmouth. We went weekly to The Four Aces and ate really good bad-for-you food. We went to the Riverside Grill and sang " You Picked a Fine Time to Leave Me Lucille" with everyone else in the joint when the song came out of the jukebox. We walked endlessly around Occom Pond, slightly worried about the bats and the occasional stray dog, and talked about what we'd do in ten, 12, 15 years. We argued with each other and lambasted the system even as we found comfort and support in this place we carved out for ourselves. I never would have imagined in my freshman year that I would look back on those days as a crucial time in my life. I wanted to get through them and out of them as quickly as possible.

out there are lapidary moments, polished by years of looking back over them. I remember a wonderfully compassionate and brilliant teacher who has since left the profession, telling me not to wish my life away. "These days, one by one, will be important to you in ways you cannot now imagine. They are the beginning of things to come. Don't underestimate them." I wrote down those words, and next to them I wrote another line he gave me, one borrowed, I now believe, from Gertrude Stein: "If you can do it then why do it?" Up until that year I'd always figured that you did whatever came easily and whatever you were good at. This teacher, among others, gave me the chance to learn to take a risk for all it was worth. If there's one lesson from my freshman year, that's it. Risking Dartmouth was, after all, worth the fear and anxiety. Risking loneliness, I found luxuriously lasting companionship. Risking rejection, I found an odd sense of acceptance. Risking failure, I found the confidence of some sort of native ability laboriously honed into skill. Risking unhappiness, I found at least measured and memorable joy. Risks are worth it.

After all, you can always take the next bus home.

Burreca felt she was theonly student whose lastname ended with a vowel.

In my most generous estimation,I looked about as preppy as Ava Gardener and sounded as calm as Ethel Merman.

For this city girl, arrival meant fear,endless adventure, and the possibilityof heading right hack home.

Regina Barreca is an associate professor ofliterature at the University of Connecticut. Perfect Husbands and Other Fairy Tales will be published next month.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureI Was A Freshman Trip Spy

September 1993 By Todd Balf -

Feature

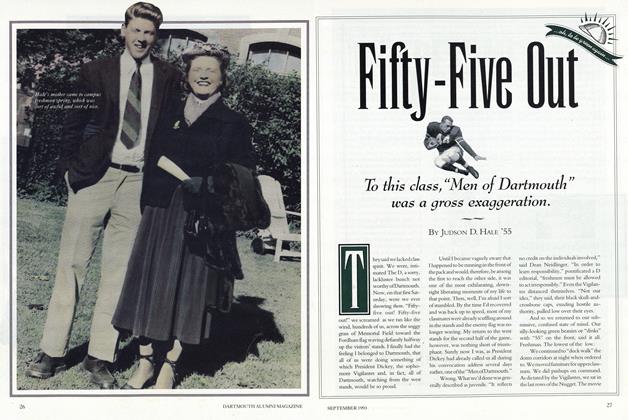

FeatureFifty-Five Out

September 1993 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Feature

FeatureThe First Year

September 1993 -

Feature

FeatureHow Do You Socialize a Freshman?

September 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThey have been called freshies, Pea Greeners, shmen a current phrase that cannot be uttered without sneering.

September 1993 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1993 By "E. Wheelock"

Regina Barreca '79

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorWhither the Greeks?

MAY 1999 -

Feature

FeatureThey Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted

June 1992 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMater Dearest

MARCH 1997 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the FALL

JANUARY 1998 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureMoney and Luck

MARCH 1999 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Feature

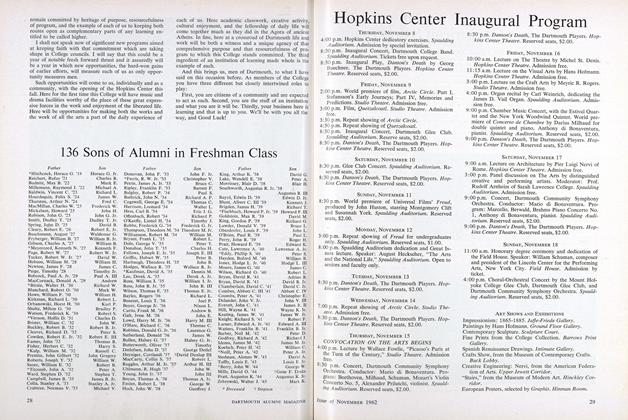

FeatureHopkins Center Inaugural Program

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

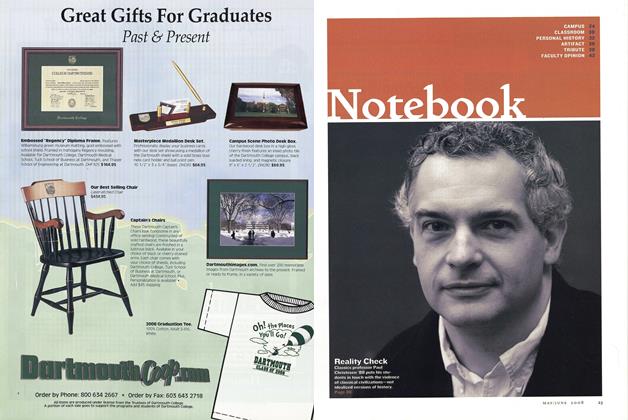

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2008 -

Feature

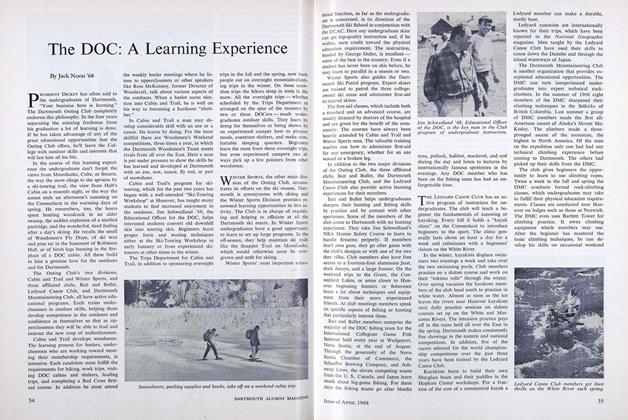

FeatureThe DOC: A Learning Experience

APRIL 1968 By Jack Noon '68 -

Cover Story

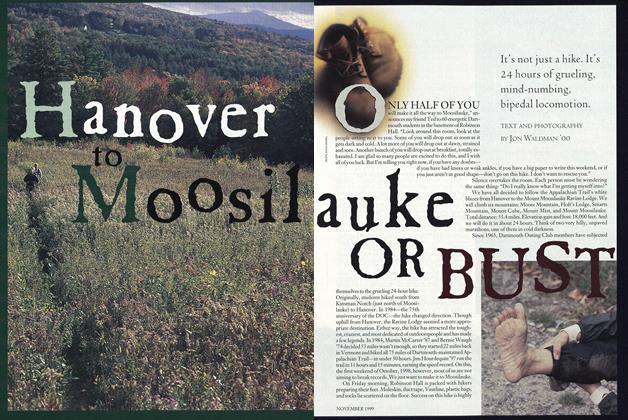

Cover StoryHanover to Moosilauke or Bust

NOVEMBER 1999 By Jon Waldman ’00 -

Feature

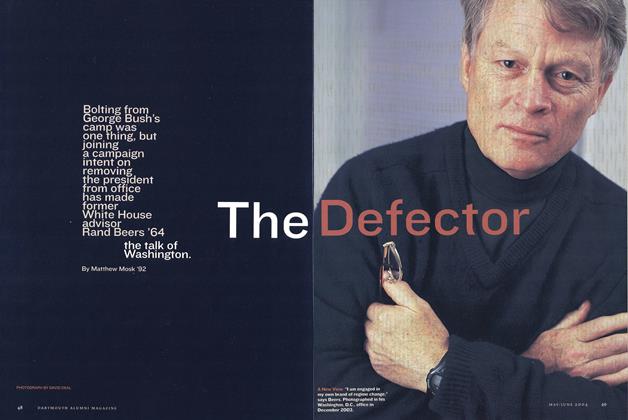

FeatureThe Defector

May/June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

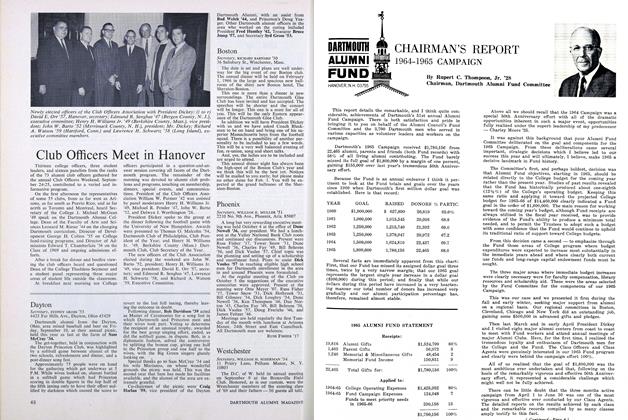

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28