CONTEMPORARY Hanover is beginning to sound a bit like Philadelphia of 1776, although this time around the battle cry is likely to be, "No tuition without representation." In what is certainly a prime manifestation of the much-touted "return to normalcy" on American college campuses, a group of Dartmouth undergraduates has banded together and is demanding the reinstitution of student government.

Followers of such things will recall that student government at Dartmouth self-destructed in the fall of 1968. Its death, some say, represented the high-water mark of student activism on campus. The first blow came in late October when the Undergraduate Council voted to abolish the student senate. "The senate failed to justify its existence," explained Samuel Faber '69, head of Palaeopitus. Five days later, ten of the 11 members of Palaeopitus resigned and issued a statement calling student government "totally unproductive." "The Undergraduate Council," they intoned, "is invalid and should be abolished now." The UGC quickly took their advice and voted 30-14 to abolish itself. The end came on November 10, when 69 per cent of those voting in a special referendum turned thumbs down on the Undergraduate Council. After reviewing the results of the referendum, the Board of Trustees signed the death certificate of the structure that had been in effect since 1947.

The demise of the "useless vestige of the past," as The Dartmouth called it, brought with it hopes for a new and more responsive structure of student government. "It's important that we realize what student government can do," said Faber, a leader in the abolition movement. "If we can get real student participation in forming and ratifying a new structure, then we feel that the students will support it and that the elected officers in the future will have a student mandate with which to work."

Things didn't work out that way. What power students had remained in the hands of the Inter-Dormitory Council (IDC), the Inter-Fraternity Council (IFC), class officers whose positions were in large part ceremonial, and an occasional student appointed to a College-wide committee or task force. There was no single central representative body to galvanize student opinion during the ROTC, coeducation, or year-round operation debates. Finally, five years after the suicide of student government, a group of students has come up with a plan which calls for a structure that, at first glance, looks suspiciously like Palaeopitus.

The planners, who represent a wide range of campus and student organizations, presently envision a body of 15 which would act as a sounding board for undergraduates, convey its conception of the undergraduate consensus on important matters to the Board of Trustees, and appoint students to College policy-making committees. (Most faculty committees which provide for student representation currently hand pick the students.) Only three members of the new government would be elected; the balance would be appointed by such organizations as Green Key, the Outing Club, Student Forum, WDCR, The Dartmouth, IDC, IFC, International Students Association, Hillel, Afro-American Society, Native Americans, and the Freshman Council.

"Just as abolition of student government was a symptom of the times, I feel that the time is now for the reinstitution of student government," says Andy Sacks '77 a member of the ad-hoc committee for reinstatement and corresponding secretary of the IDC. "There is no group that can be consulted effectively or that can speak for the students as an undergraduate body," says Sacks, who feels that the new student government would fill this void. He cites two recent campus issues which had "insufficient student input." First, he says, the Dartmouth Plan Office last spring was forced to reject some freshman year-round operation attendance patterns because of anticipated overcrowding during the fall term. "There was no student consultation on that," says Sacks. The faculty's abortive plans to revise the honor code also drew Sacks' criticism. "Here's an attempt to change policy that would affect every single student, yet there was minimal student input," he says.

Sacks defends the notion of legitimizing the present student power structure by appointing most members from established student organizations rather than having broad-based elections. "It wouldn't be effective if you didn't have representatives from the IDC, IFC, The Dartmouth, and so forth."

"John Dockum '75, another member of the steering committee, is a bit more specific in his criticism of the present system and quite vocal in his opposition to the plan most likely to be presented to students for their approval. "There has got to be a structure to give students some say in things going on here," he says. "There have been too many arbitrary decisions made by the Kemeny team - in this last year particularly - and I don't think they've had a very good track record in eliciting student opinion."

"The student power structures that exist today don't have any legitimacy," says Dockum. "The IDC and IFC stick their fingers in all the pies without having the authority to do so. This is why student government is an idea whose time has come. It's as simple as that." Dockum, executive editor of The Dartmouth, resists the idea of institutionalizing the present student power structures. The present plan, he says, "reeks of experienced student bureaucrats." Instead of resorting to what he calls "the student-politico mentality," Dockum feels that the group should hold "open meetings to find out what the students are thinking." Otherwise, he warns, the plan is doomed to failure.

"The last year has seen some awfully poor decisions on the part of the administration and I don't think that students could do worse," he continues. He cites the removal of the Indian symbol, the problems with the Dartmouth Plan, and housing as areas in which a student government could have provided constructive student input.

In any case, it seems likely that by next fall, students will have a say in the way the College is run. "It'll be a step forward," concludes Sacks. All the way to 1968.

This year's undergraduate editor, VictorZonana also will take on somewhat expanded responsibilities as the Magazine'sfirst Whitney Campbell 1925 Intern. FromBrooklyn, N.Y., he is an associate editorof The Dartmouth and for the last threemonths was a reporter with the Pittsburghbureau of The Wall Street Journal. Established by Robert Borwell '25 inmemory of his classmate WhitneyCampbell, the internship is to provide undergraduates with practical experience injournalism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"THE KINGDOM OF GOD HAS COME"

October 1974 By MARy BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

FeatureMountain of Storms

October 1974 By ANDREW HARVARD, TODD THOMPSON -

Feature

FeatureBelieve It or Not!

October 1974 By GREGORY C. SCHWARZ -

Article

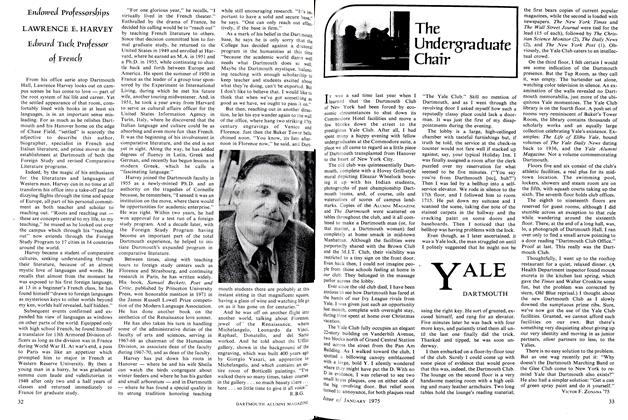

ArticleBig Green Teams

October 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1974 By WALTER C. DODGE, DR. THEODORE MINER