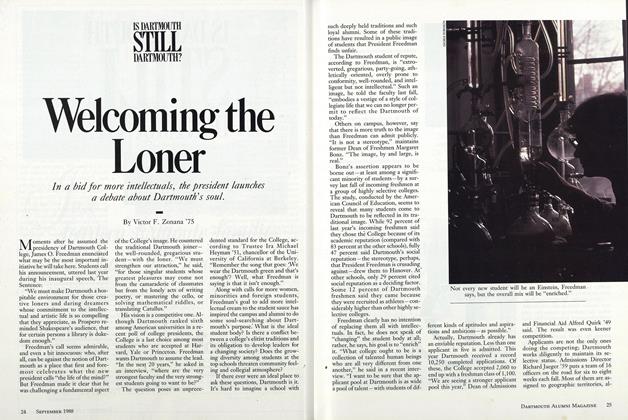

THERE are signs this fall that the issue of ROTC, a focus of controversy during the turbulent sixties, will once again roil the waters of an otherwise calm campus. What began as a trickle of letters to the editor of The Dartmouth last spring when the Trustees established an Ad Hoc Committee on ROTC became a freshet last month as the committee issued its interim report. Those who had proclaimed apathy the ruler on campus had second thoughts as more than 100 students turned out on the eve of Houseparties for an open hearing on ROTC.

The arguments presented by speakers at the hearing were little changed from those made during the first go-around in 1969, although this time they lacked the ardor and emotion sparked by the immediacy of the war in Vietnam. Nonetheless, the ghost of American involvement in Southeast Asia hung heavy in the room as speaker after speaker invoked Vietnam to make a point, either pro or con. Those against ROTC called Vietnam an example of what's wrong with the military and why it should be kept off campus. Those favoring reinstatement said that more ROTC officers trained at liberal arts institutions might humanize the military and prevent future Vietnams from occurring.

The format for the hearing was decidedly simple: A moderator recognize those raising their hands, the speakers made brief statements for or against reinstatement (usually against), sat down, and listened to the next person. No interruptions, no raised voices, no heckling - indeed, in the words of one observer, the proceedings were "frightfully polite." The only demonstration that took place was a symbolic one; many members of the antiROTC faction - no doubt veterans of the anti-war era - showed up wearing black armbands.

Sentiments ran heavily against ROTC. No more than five students spoke in favor of reinstatement, although a sizeable contingent of alumni in Hanover for the Club Officers meeting frequently joined forces with the pro-ROTC students. ROTC supporters blamed their relatively poor showing on the lack of organization on their side, but it seems clear that campus-wide, the majority of students having an opinion on the issue oppose campus military training. (In a student referendum held in April 1969, almost 60 per cent of those voting called for elimination of ROTC programs, either immediately or as students then enrolled were graduated. More than three quarters (1,907) asked the faculty to reconsider its recommendation that "Dartmouth take steps to collaborate with other institutions of higher education in developing a plan for transferring all ROTC military courses to summer camps" while maintaining the ROTC option for Dartmouth students.)

Speakers favoring reinstatement repeatedly stressed three points. They argued that ROTC-trained officers would help "humanize" the armed forces, that ROTC would provide needed financial aid for Dartmouth students in the program, and that ROTC at Dartmouth would strengthen the nation's defense posture. Contrary voices repeatedly cited the "evils" of the military, and questioned why the military should be granted a special concession and be allowed to set up a training program at Dartmouth.

"There is a positive benefit in having college students in the military," argued John Hart '75. "Dartmouth students can work to make the military a more positive and sensitive and humane institution," he said, adding that "the United States must maintain a defense posture."

"I'm not robbed of the opportunity of joining the military when I come to Dartmouth," answered Gerry Rosenberg '76. "If I want to go in and humanize the Army, I can do it after I get out of Dartmouth." Added another student in a black armband, "If Vietnam is an example of humanism [introduced into the Army by ROTC], then we don't need any more."

Much of the talk at the hearing centered around the nature of the military, rather than on the nature of ROTC. "To accept ROTC again at Dartmouth would be to condone the immoral actions of the military," said a coed. She didn't specify what the immoral actions were but many in the audience seemed to know, for her statement was greeted by a round of applause. Another student spoke of napalm and bullets, while a professor from the Medical School said a few words about distorted priorities. "The Navy discipline is close the mind and follow the leader," added a lecturer in the English Department.

William De Stefano '46 tried to counter some of the anti-military arguments. "We're forgetting that the military is an establishment of the political branch of government," said De Stefano, a Naval ROTC graduate. "The military does not establish policy." He suggested that it was irrational "to vent anger at the military and ignore the political establishment." But John Lamperti, Professor of Mathematics, countered by quoting a retired general who said that it was "a fiction that the military is a creation of the civilian government." Lamperti added that the military agitated for escalation during the Vietnam war.

The financial aspects of the question were debated by several speakers, but the discussion got nowhere and was effectively terminated when Gerry Rosenberg got ubp again and said, "Money can never be an argument if you have principles."

Perhaps the ROTC opponents' most effective argument was made by Andy Johnson '75, president of the Dartmouth chapter of Young Democrats. He said that bringing back ROTC "would give the military higher priority than anyone else at Dartmouth." Dartmouth College, he said, is a liberal arts institution "that does not provide vocational training." He said that "we don't give such special concessions to any other organization or industry" and that students are free to go into the armed forces after they leave Dartmouth, just as they are free to join a corporation or other organization.

Several participants were disappointed that the meeting never got around to discussing the six possible alternatives for the College as outlined in the report by the Trustees' Ad Hoc Committee. Complained Professor of Government Lawrence Radway, "The arguments haven't changed since 1969. Talk of napalm and bullets just don't make for an intelligent discussion."

That's basically how things went at the committee's open hearing. Few if any minds were changed, but perhaps the most significant thing about the meeting was that proponents on both sides of what has been a very divisive and controversial issue on campus were able to sit down together and make their views known in an atmosphere of mutual respect.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: More Food for Thought

December 1974 By JOAN L. HIER -

Feature

FeatureSheets of Sound

December 1974 By SID LEAVITT -

Feature

FeatureChartres in a Chevrolet

December 1974 By ROBERT L. McGRATH -

Feature

FeatureOur Crowd

December 1974 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

December 1974 By PAUL WOODBERRY, CHARLES S. KILNER