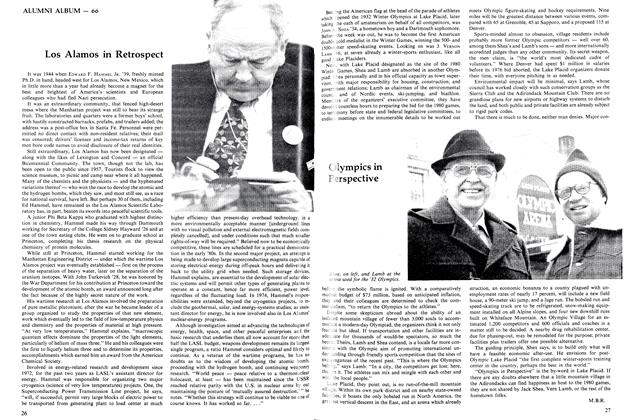

Cheap abundant fuel, constantly and instantly available, has probably gone the way of the nickel beer or the penny postcard, a victim of global inflation and the inexorable law of supply and demand. And anyone thinking wishfully to the contrary will get small comfort from RICHARD A. HOWE '46, who should know whereof he speaks.

Howe has been with Mobil Oil for 27 years, from his start as a field geologist in the Colombian jungles through successive assignments, mainly in exploration in the West, to his current position as president of Mobil-Venezuela. For the two years before becoming top man in Caracas last spring, he was worldwide explorations manager at New York headquarters. But, he makes clear, his overview of the energy situation is strictly his own and not necessarily Mobil's.

He assumed responsibility for the Venezuelan company, an explorations-to-marketing operation employing 930 people (98 per cent of them Venezuelans), at a critical time in the volatile world of petro-politics. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) had boosted the price of crude by some 400 per cent, with still incalculable effects on world economy, and industrial nations were pinched by the Arab oil embargo, which Howe calls "a mighty effective form of retaliation for a U.S. imbalanced Mideast policy and oversupport of Israel."

Even with the increase, Howe maintains that fuel, long underpriced, is not far out of line. A gallon of regular gasoline, he points out, has risen 74 per cent since 1960, the same as a pack of cigarettes, considerably less than most meats, not much more than the consumer price index average. He sees oil prices, down slightly from peak, remaining stable for six to ten months, by which time "something tied to world economic conditions and oil's true value will have been worked out." With the aim of last year's embargo, "a change in U.S. attitude and policy toward the Middle East," accomplished, he doubts it will be reinstated.

"The question of oil pricing is staggeringly complex," Howe says. "OPEC basically says that oil prices should be tied to worldwide inflation. Worldwide inflation is rampant partly because OPEC pushed prices up four-fold last fall and winter when they had the crisis opportunity. ... Now the struggle is between consuming and producing nations over inflation each block claiming the other 'got us into this inflation spiral.' " A further complication was the decision of several countries, Venezuela among them, to lower production - "ultimately their sovereign right," Howe acknowledges. Essentially, he says, they are banking in the ground "an irreplaceable asset whose rate of increase in value has been higher than interest rates or other investment yields."

Since fossil fuels will fill a decreasing percentage of energy needs as other sources, principally nuclear, are developed, Howe sees no long-run crisis in energy supply, but he warns that a serious short-term shortage of indigenous supply" means "10 to 15 years of being at the full mercy of oil imports."

He is skeptical, to say the least, about meeting the 1984 target date of Project Independence. To do so, Howe thinks, would reuire an almost impossible combination of highly unlikely circumstances. The principle of doing without imports would have to be important enough to the American public as individuals to justify the sacrifice of their high-energy-consumption life style, their money, and their environment. Through their elected representatives they would have to make the business environment sufficiently attractive to encourage wide development of non-conventional hydrocarbon sources - mainly coal and oil shale - at exorbitant cost. They would have to accede to the relaxation of environmental controls to an unprecedented degree to permit crash programs in such development.

"I just don't think the average citizen is willing to pay just any price, however high, to bask in the security of self-sufficiency," Howe says. Nor does he consider 100 percent self-sufficiency necessarily in our best interest. "Petroleum is the biggest single item in world trade," he notes, and developed and developing nations are "all pretty close together here on Spaceship Earth. International trade, goods for goods, is a healthy relationship in the long run."

Concern for the environment has had both beneficial and unfortunate results, Howe thinks. On the one hand, there are sound new regulations governing drilling and production practices formulated after the Santa Barbara spill; on the other, a costly delay in constructing the Alaska pipeline. "One can argue till doomsday as to what is too much or too little environmental protection," he says. "In the long run we will have that amount of control we are willing to pay for in terms of dollars and cents, along with a touch of reduced life style." He is concerned lest "we toss environmen- tal control progress to the winds just in the vain hope of having abundant cheap fuel again."

Mr.and Mrs.Howe, whose children - including Steven '70 - are "scattered across the U.S," find the Venezuelan people cordial toward Americans on a grass-roots level. But on another plane, attitudes are changing rapidly as a result of recent hard-line remarks aimed from Washington at the oil-producing nations, Howe says. For right or wrong, "Venezuelans are mad, perhaps a little hurt, certainly offended by the new U.S. official attitude."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

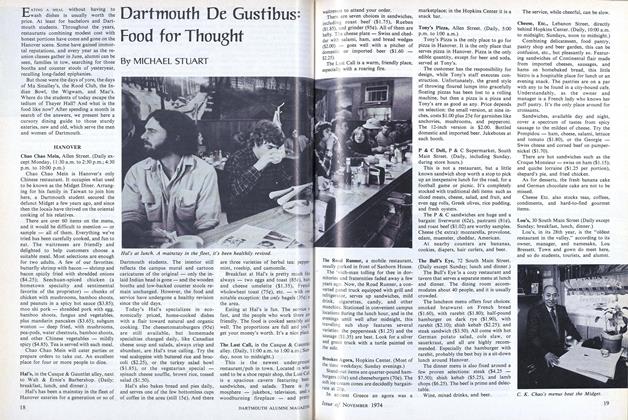

FeatureDartmouth De Gustibus: Food for Thought

November 1974 By MICHAEL STUART -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

November 1974 By V.F.Z. -

Feature

FeatureYou Can Go Home Again

November 1974 By DICK REDINGTON '64 -

Feature

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1974 By JACK DtGANGE -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

November 1974 By J.H.

M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Coaching Staff

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleRecord Fund Hits $2,464,201

OCTOBER 1971 -

Article

ArticleFour Things Probably Never Knew About the Dartmouth College Case

June 1989 -

Article

ArticleClass of 2019

APRIL 1998 -

Article

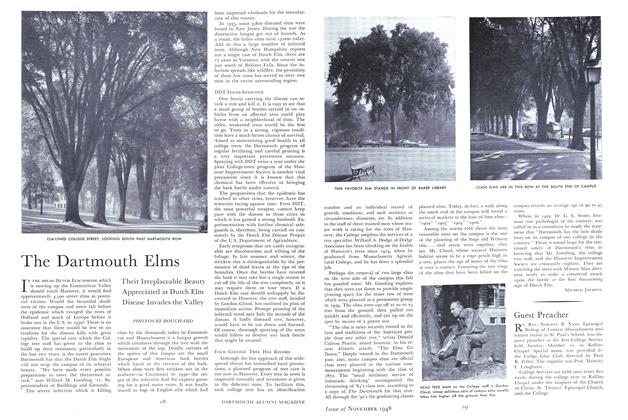

ArticleThe Dartmouth Elms

November 1948 By Mildred Jachens.