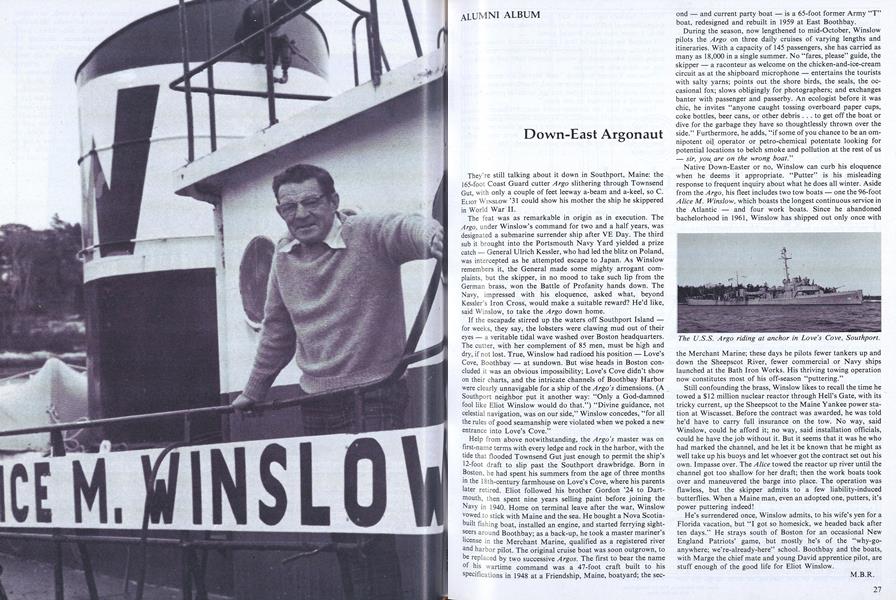

They're still talking about it down in Southport, Maine: the 165-foot Coast Guard cutter Argo slithering through Townsend Gut, with only a couple of feet leeway a-beam and a-keel, so C. ELIOT WINSLOW '31 could show his mother the ship he skippered in World War II.

The feat was as remarkable in origin as in execution. The Argo, under Winslow's command for two and a half years, was designated a submarine surrender ship after VE Day. The third sub it brought into the Portsmouth Navy Yard yielded a prize catch - General Ulrich Kessler, who had led the blitz on Poland, was intercepted as he attempted escape to Japan. As Winslow remembers it, the General made some mighty arrogant complaints, but the skipper, in no mood to take such lip from the German brass, won the Battle of Profanity hands down. The Navy, impressed with his eloquence, asked what, beyond KesslerKessler's Iron Cross, would make a suitable reward? He'd like, said Winslow, to take the Argo down home.

If the escapade stirred up the waters off Southport Island - for weeks, they say, the lobsters were clawing mud out of their eyes - a veritable tidal wave washed over Boston headquarters. The cutter, with her complement of 85 men, must be high and dry, if not lost. True, Winslow had radioed his position - Love's Cove, Boothbay - at sundown. But wise heads in Boston con- cluded it was an obvious impossibility; Love's Cove didn't show on their charts, and the intricate channels of Boothbay Harbor were clearly unnavigable for a ship of the Argo's dimensions. (A Southport neighbor put it another way: "Only a God-damned fool like Eliot Winslow would do that.") "Divine guidance, not celestial navigation, was on our side," Winslow concedes, "for all the rules of good seamanship were violated when we poked a new entrance into Love's Cove."

Help from above notwithstanding, the Argo's master was on first-name terms with every ledge and rock in the harbor, with the tide that flooded Townsend Gut just enough to permit the ship's 12-foot draft to slip past the Southport drawbridge. Born in Boston, he had spent his summers from the age of three months in the 18th-century farmhouse on Love's Cove, where his parents later retired. Eliot followed his brother Gordon '24 to Dartmouth, then spent nine years selling paint before joining the Navy in 1940. Home on terminal leave after the war, Winslow vowed to stick with Maine and the sea. He bought a Nova Scotiabuilt fishing boat, installed an engine, and started ferrying sightseers around Boothbay; as a back-up, he took a master mariner's license in the Merchant Marine, qualified as a registered river and harbor pilot. The original cruise boat was soon outgrown, to be replaced by two successive Argos. The first to bear the name of his wartime command was a 47-foot craft built to his specifications in 1948 at a Friendship, Maine, boatyard; the second - and current party boat - is a 65-foot former Army "T" boat, redesigned and rebuilt in 1959 at East Boothbay.

During the season, now lengthened to mid-October, Winslow pilots the Argo on three daily cruises of varying lengths and itineraries. With a capacity of 145 passengers, she has carried as many as 18,000 in a single summer. No "fares, please" guide, the skipper - a raconteur as welcome on the chicken-and-ice-cream circuit as at the shipboard microphone - entertains the tourists with salty yarns; points out the shore birds, the seals, the occasional fox; slows obligingly for photographers; and exchanges banter with passenger and passerby. An ecologist before it was chic, he invites "anyone caught tossing overboard paper cups, coke bottles, beer cans, or other debris ... to get off the boat or dive for the garbage they have so thoughtlessly thrown over the side." Furthermore, he adds, "if some of you chance to be an omnipotent oil operator or petro-chemical potentate looking for potential locations to belch smoke and pollution at the rest of us - sir, you are on the wrong boat."

Native Down-Easter or no, Winslow can curb his eloquence when he deems it appropriate. "Putter" is his misleading response to frequent inquiry about what he does all winter. Aside from the Argo, his fleet includes two tow boats - one the 96-foot Alice M. Winslow, which boasts the longest continuous service in the Atlantic - and four work boats. Since he abandoned bachelorhood in 1961, Winslow has shipped out only once with the Merchant Marine; these days he pilots fewer tankers up and down the Sheepscot River, fewer commercial or Navy ships launched at the Bath Iron Works. His thriving towing operation now constitutes most of his off-season "puttering."

Still confounding the brass, Winslow likes to recall the time he towed a $12 million nuclear reactor through Hell's Gate, with its tricky current, up the Sheepscot to the Maine Yankee power station at Wiscasset. Before the contract was awarded, he was told he'd have to carry full insurance on the tow. No way, said Winslow, could he afford it; no way, said installation officials, could he have the job without it. But it seems that it was he who had marked the channel, and he let it be known that he might as well take up his buoys and let whoever got the contract set out his own. Impasse over. The Alice towed the reactor up river until the channel got too shallow for her draft; then the work boats took over and maneuvered the barge into place. The operation was flawless, but the skipper admits to a few liability-induced butterflies. When a Maine man, even an adopted one, putters, it's power puttering indeed!

He's surrendered once, Winslow admits, to his wife's yen for a Florida vacation, but "I got so homesick, we headed back after ten days." He strays south of Boston for an occasional New England Patriots' game, but mostly he's of the "why-go-anywhere; we're-already-here" school. Boothbay and the boats, with Marge the chief mate and young David apprentice pilot, are stuff enough of the good life for Eliot Winslow.

The U.S.S. Argo riding at anchor in Love's Cove, Southport.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

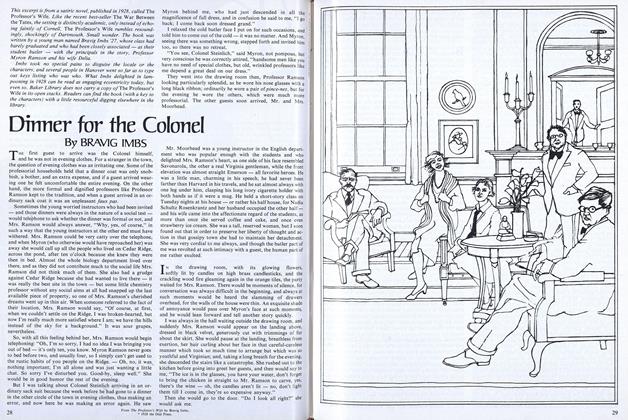

FeatureDinner for the Colonel

March 1977 By BRAVIG IMBS -

Feature

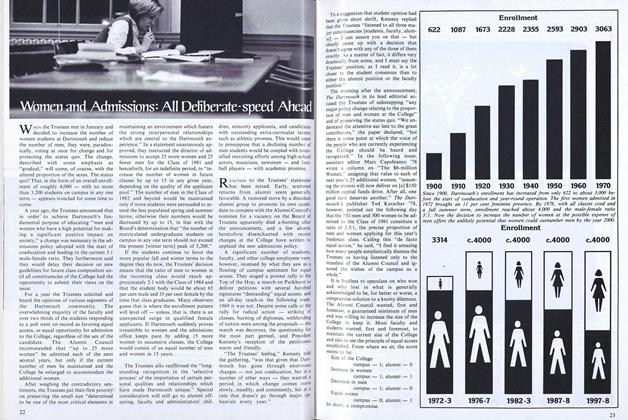

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Feature

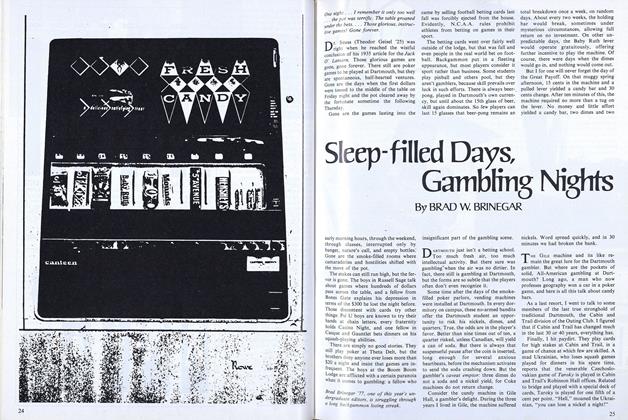

FeatureSleep-filled Days, Gambling Nights

March 1977 By BRAD W. BRINEGAR -

Feature

FeatureArtists

March 1977 -

Article

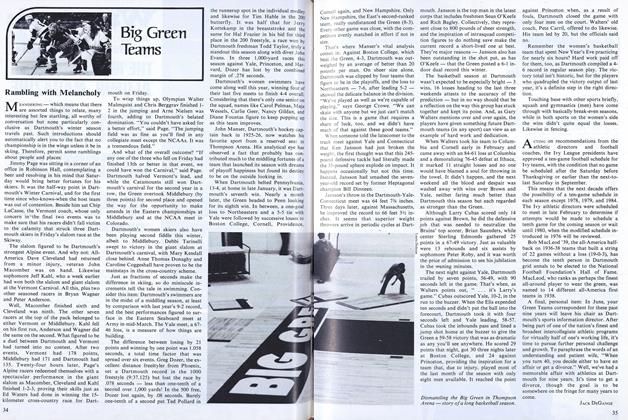

ArticleRambling with Melancholy

March 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G.

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeatureConserver of Life

April 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleOlympics in Perspective

April 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleEqual Opportunity: efforts to make it more equal

June 1976 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleSky Watcher

JAN./FEB. 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleWriter Possessed

JAN./FEB. 1979 By M.B.R.