Bound handsomely in blue, with grants from three foundations, 46 contributors, original poems, translations from' nine different languages, book reviews, and essays, Granite, the magazine. Number 6, Autumn 1973, though edited and printed in Hanover, is now circulating throughout the United States. The editors are a Dartmouth Assistant Professor of Russian, George M. Young Jr., and an M.D., a resident in Psychiatry at the Hanover Mental Health Center, Anselm Parlatore. The managing editors are Dorothy Beck, formerly connected with the Dartmouth College Library Archives and now an executive at the Dartmouth Printing Company, and Marnie Rogers, a teacher at the Hanover High School. Published twice yearly, the magazine costs $2 or three issues for $5, and checks may be sent to Box 774, Hanover.

Richard Eberhart '26, whose latest book is Fields of Grace, contributes an essay entitled “Literary Death" in which he recalls his response to the demise of some poets among his acquaintances, friends, or idols. When Hardy died, the Cambridge (England) bells tolled for him and also for Eberhart. A few snowflakes descended on the coffin of Ted Spencer. When F. O. Matthiessen jumped out of a window of the 13th story of the Hotel Manger, it was the first of that month which Eliot called the most cruel: April. Jeffers' death induced no Eberhart tears, for his poems "were hard as mountains." The wildness ' of Dylan Thomas's death "brought tears gushing for days." "UnFrostian" for a man so earthy was Robert Frost's cremation. "For Shelley, yes; for Frost, no." When Ted Roethke died, it was "a muffling of drums."

For Richard Eberhart, Litt. D., Class of 1925 Professor and Professor of English Emeritus, death used to be "mystical anguish." Later it became the great individualist," and in varying metamorphoses changed to "master dictator, infidel clown, ... a howling success ... a bore." He resents death because it forces him to write about it rather than about life, and for over 40 years he has been "partially seduced in this way."

Prof. Thomas H. Vance and his Swedish wife Vera, are major contributors. Mrs. Vance is author of three poems in English, and she and her husband offer translations from French, German, and Swedish poets. Tobias Berggren writes in Granite about the miners' strike during the winter of 1969-1970. His two books of published poems are entitled The Necessary IsNut Clear (1969) and The Foreign Security (1971).

Elsewhere Mrs. Vance has translated a collection of short stories by the Danish writer Hans Christian Branner entitled Two Minutes ofSilence, and with her husband a number of contemporary Norwegian poems. Mr. Vance is author of Skeleton of Light published by the University of North Carolina Press. In a forthcoming issue of Granite the Vances will offer translations from a young Swedish poet, Nils-Ake Hasselmark, connected with the writer-owned publishing cooperative Forfattar- forlaget.

Robert Eaton Kelley '61 of Chicago is hard at work on his third novel. He has completed his second, entitled Long Time Dying, and it is now making the rounds of publishing houses. The semi-annual literary magazine, Bachy, located in Los Angeles, has allotted 17 pages in the July 1973 issue to "Mr. Duck Emerges," extracted from Mr. Kelley's first novel, Mr. Duck Or IntoThe Millennium.

In the belief that strong and new world voices must be heard and that African, Native American, Third World, and American poets, so vital to contemporary verse, should be published, The Greenfield Review Press in 1973 began a series of chap books. Nine titles have so far been published, and more are on the way. Among those forthcoming is The Intercourse by David Rafael Wang '55, who continues to make himself heard in both prose and poetry. At a meeting during the Christmas holidays of the Modern Language Association he delivered a paper on the use of Chinese mythology in Ezra Pound's poetry. Wang poems have appeared recently in The Remington Review, TheAmerican Pen, and The Greenfield Review. One, "The Retriever," recalls a Dartmouth experience in its reference to "the dark New Hampshire woods," and "the Occum Pond," the spelling of which he took the liberty of altering. One might suggest that he is in the best traditions of The Greenfield Review, the brochure of which pedagogically refers to the importance of "contemparary [sic]" poetry and alters the spelling of Mr. Wang's middle name. Rivers on Fire is the title of the volume of his poems to be published next year by the Basilishk Press of Dunkirk, N.Y.

Would your answers be yes or no to these questions?

Should children be adopted even before they are born? Should customary trial periods with the option of the natural parents to change their minds be eliminated?

Should each situation about the placement of children be considered an emergency requiring a swift and final decision?

Should the custodial parents have the final say in divorce cases when the court keeps hands off, except to award custody, and when the parents cannot agree about any matters regarding the children's upbringing?

Are United States courts at fault as they redirect each year the lives of tens of thousands of children who become the objects of custody battles arising from adoption, foster care and divorce proceedings?

If your answers are all yes, you agree with the three authors of a radical book who believe firmly that family court policies endanger the development of children and that the country should speedily introduce major fundamental reforms. Entitled Beyond the Best Interests ofthe Child (A Free Press Paperback. $1.95, hardcover $7.95, Macmillan Publishing Company, Inc., 170 pp), the authors are Joseph Goldstein '44, Walton Hale Hamilton Professor of Law, Science, and Social Policy at Yale University Law School; Anna Freud, Director of the Hampstead Child Therapy Clinic; and Albert J. Solnit, Sterling Professor of Pediatrics and Psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine.

Beyond the Best Interests of the Child has received favorable reviews by judges, lawyers, child welfare workers, critics in law quarterlies and medical journals, and physicians, who agree that if the guidelines of the book were put into practice, thousands of children would be saved from needless emotional damage. Rita Kramer in The New York Times Magazine believes that the book "may well become as controversial as Freud's writings were to the medical and psychological establishments of his day."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

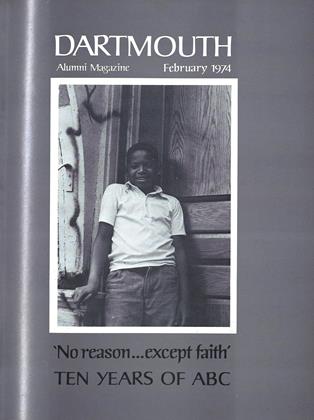

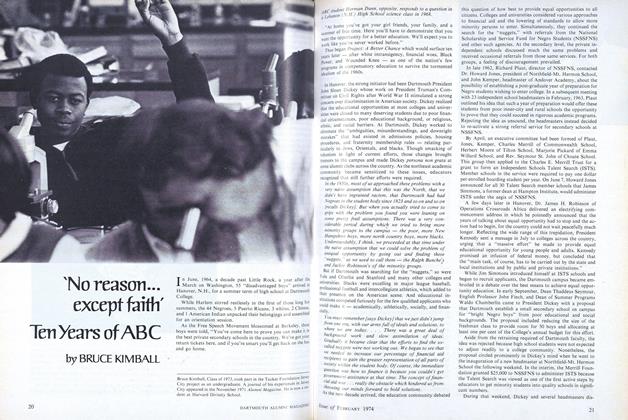

Feature‘No reason... except faith' Ten Years of ABC

February 1974 By BRUCE KIMBALL -

Feature

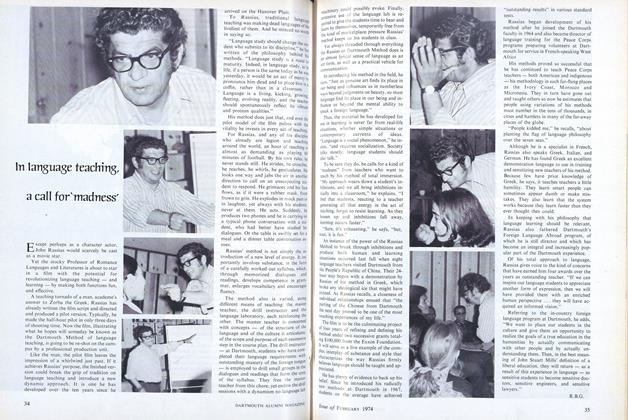

FeatureIn language teaching, a call for ‘madness'

February 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

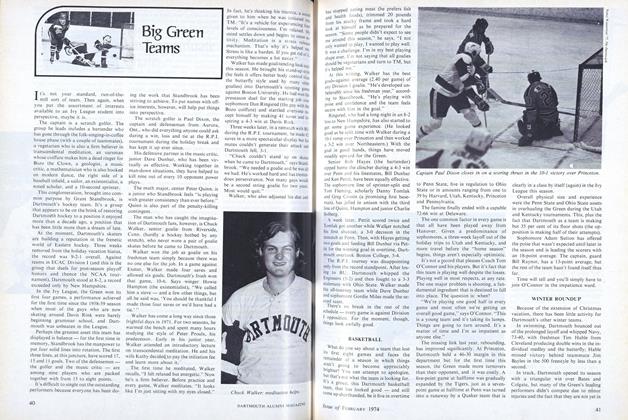

ArticleBig Green Teams

February 1974 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

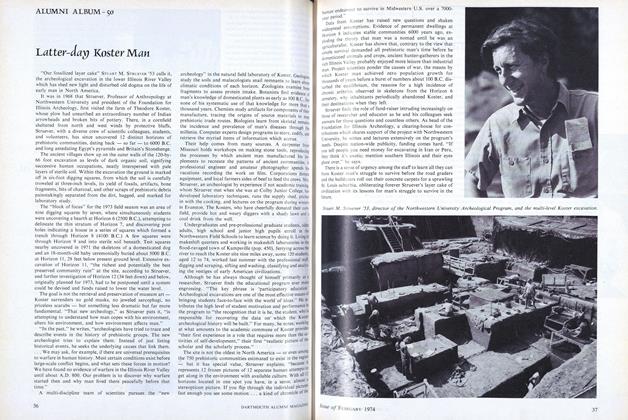

ArticleLatter-day Koster Man

February 1974 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1974 By JACQUES HARLOW, ERIC T. MILLER -

Article

ArticleHEINZ VALTIN

February 1974 By Andrew C. Vail Memorial, R.B.G.