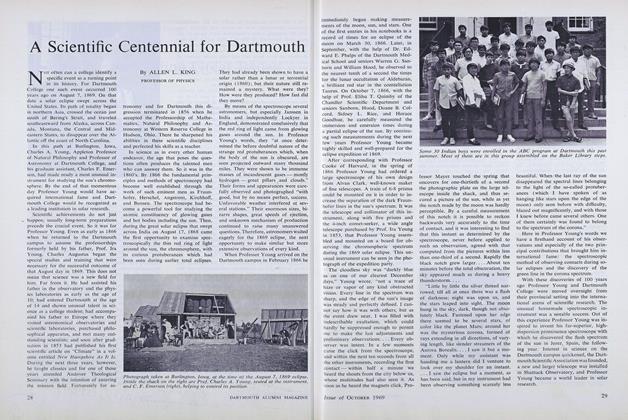

AT the age of 59 the Reverend Doctor Eleazar Wheelock in faith and with determination set out to move his school and his household "lock, stock and barrel" from Lebanon, Connecticut, to the wilderness of New Hampshire. Here he would establish a new life and a new school dedicated afresh to the work of God. He would prepare young men of the colonies and especially Indian youths for missionary work among the tribes. But before instruction could begin he must clear the land, plant seed, erect buildings, and establish a community of his faithful followers. The Doctor had supreme confidence in the Tightness of his venture; he was doing God's will as a trusted servant. How could he fail?

The first winter of 1770-71 was harsh, food scarce. The students huddled in huts around the Wheelocks' windowless log cabin. Sometimes miserable and cold, they also were imbued with the enthusiasm and warmth of their teacher and spiritual leader. With the help of the few early settlers they built their College, the first Dartmouth Hall: dormitory, classrooms, and commons all under one roof. Then sawmill and gristmill, bake house and wash house, malthouse and storehouse, barn and blacksmith shop, houses for doctor, shoemaker, tailor, carpenter and mason — all needed building. Clear more land; burn the brush; plant more fields; harvest the crops; pasture more cattle; raise more sheep. Carve out a patriarchate from the wilderness.

Eleazar Wheelock never lost sight of his goal, although he was continually diverted from it by the exigencies of the moment and lack of funds. When his wife Mary and their children arrived in late 1770, they occupied the log cabin and then, as soon as it was built, the more roomy college storehouse. Eleazar was not fond of the place. In a letter of May 10, 1773, to John Thornton, a member of the English Trust, he complained:

My necessities really call for help. I have no other place for study, retirement, lodging, and to receive all my company on private business, but a little smoky room of about twelve or fourteen feet square, which I made in the garret of the one-story house... which I originally planned for a storehouse for the school, and which is now used for that purpose; and I am in no capacity to build, not being able yet to make sale of the little interest left in Connecticut, since the inhabitants are so many removed from that place, and so many would remove if they could sell their livings at almost any rate. I have drawn a bill on you, of this date, of one hundred pounds.

The Doctor dreamed of a more spacious house with a large study and airy rooms, an abode more fitting for the President of Dartmouth College, head of Moor's School, and minister of his flock. As Providence would have it, only the day before he wrote this letter there arrived in Hanover a master carpenter from Connecticut who could build his dream house.

The Wheelocks' older daughter Mary had moved out of the storehouse in February 1772 to become the wife of tutor Bezaleel Woodward, who had built a two-story dwelling on an acre of land at the north end of the Green. Even so, the crowding had been only partially alleviated. Four sons and a daughter still remained: the oldest, poor Ralph, an epileptic; John, future President of the College; Eleazar Jr.; James, the youngest; and Abigail, betrothed to tutor Sylvanus Ripley. Moreover, the extended family was growing rapidly; the College needed more space for storage, more student rooms, and larger quarters for the kitchen and commons. And Wheelock's followers needed a meeting house.

In spite of his statement to John Thornton of having "no capacity to build," Eleazar Wheelock announced to the English Trust only two months later, in July 1773, that he had begun building his house without knowing "how to support the expense of it, unless by the unbounded liberality of one of your number, by whom I have had the greater part of my support since I came into the wilderness." That month he ordered 30,000 feet of "good boards" from Thomas Johnson, a sawyer of Newbury, Vermont.

Master carpenter Hezekiah Davenport had arrived in Hanover "on a venture with tools and workmen." By July Wheelock had engaged him to build his house, two stories high, surmounted by a gambrel roof with three dormers front and rear for light into student rooms. The house would have a foundation of locally quarried granite blocks spaced with windows for light into additional student rooms in the basement. It would sit high on the knoll opposite the College, facing westward, and a flight of steps would ascend to the main entrance with its portico flanked by a pair of columns and surmounted by a balustrade. The architecture would resemble many mid-18th century homes in Connecticut, where Davenport had received his training as a carpenter and builder of houses.

The heavy-timbered frame for each side was built on the ground and raised by brute force. Villagers and students joined the work crew in the raisings. Ebenezer Mattoon, of the Class of 1776, years later related how the east frame, partly hoisted, very nearly overpowered them. Before relief came the strain of holding the side up had been so great that blood oozed from the nostrils of several men. By October 15 Eleazar wrote in his diary: "fourteen [men] employed about my house to prepare for my removal into it as soon as may be" and on November 18 the single line: "removed to live in my own house." The occasion is commemorated in a letter to John Thornton, his principal benefactor, written a month to the day after the move:

... accordingly I entered upon building a decent and convenient house for two Families [the newly married Ripleys probably shared it] as ye may be occasion for it if God shall see fit to lengthen out my life or my wife's a few years, and I have set up one of 46 by 36 feet and two stories high, the frame is good, the chimneys I think are well built. I have covered and enclosed it, made rough partitions so as to render it comfortable for my family and now removed into it and it will also furnish several comfortable rooms for my students in which I have expended about £ 250 sterling a small part of which I have paid with my own estate, and for the rest have made use of money put into my hands by this province for Building the New College which must be refunded as soon as it shall be needed for that purpose....

Thornton replied that he was pleased to learn of the comfortable habitation and with great cheerfulness would assist Wheelock whenever necessary.

I have found no description for the interior of the Wheelock mansion of 1776; but from plans for other colonial houses of the same style and from clues found in the structure as it exists today we can surmise how the arrangement of rooms and general layout may have appeared to a visitor of that period. On stepping through the main entrance into the wide hallway that bisected the house, he sees straight ahead a great central stairway to the second floor and beyond it at the far end a large window overlooking the wooded hills to the east. At his left the door to the Ripleys' quarters is closed. He enters the door at his right into the Wheelocks' spacious parlor or drawing room with its large fireplace against the south wall. Through the front windows he notes a gathering of students outside the entrance to the College across the way. And glancing around the room he is struck by the plain sturdy furniture and simple tastes of the inhabitants of the house.

Through a wide doorway at the middle of the east wall he enters the great dining room which occupies the entire southeast corner of the main house. It is sufficient to accommodate more than a dozen guests. Beyond it through an open door he can see a commodious keeping room with all the appurtenances of a colonial kitchen, including sink, table and benches, and a great fireplace at the far east side equipped with the usual spit, pothook, tripod, and caldron. There is a pantry convenient to the dining room, and in the northeast corner a back stairway reaches to the upper floor of the two-story wing. On the south side a door opens onto the Wheelocks' porch which overlooks the garden and serves as the principal entrance for the family. Through it water is easily fetched from the well.

If the visitor were to go upstairs he would find Eleazar's study and bedroom above the parlor, as spacious and airy as had been dreamed, and beyond it bedrooms for his children and perhaps a small storeroom at the head of the back stairway. The Ripleys' bedrooms occupy the north side of the second story in the main house, and at the end of the upper hallway a steep stair serves the students whose rooms are under the roof.

Although the Ripleys at times may have shared the facilities of the Wheelock kitchen, more than likely they had their own small kitchen in the northeast corner of the main house with a doorway to the east porch. Here they lived until Wheelock's death and his son John's assumption of the estate in 1779.

At an age well beyond the average life span of his day and when modern men look toward retirement, the Reverend Doctor Eleazar Wheelock' launched upon a new life in a new country where the winters often were harsh and the summers filled with hard work. There he built a new school and established a thriving community within the remaining nine years of his life. He fulfilled his dream of building his own house hard by his College. Though moved across the campus to West Wheelock Street and changed in roofline, portico, interior walls and stairs, the mansion still stands, the only surviving structure and monument to Wheelock's perseverance and faith and dream come true.

The artist s rendering above shows the Wheelock house as it probably appeared uponcompletion. Later shorn of its architectural finery and gambrel roof, the building wasmoved to West Wheelock Street where until recently it housed the Howe Library.

Allen L. King, professor of physicsemeritus, wrote about Dartmouth's collectionof 19th-century scientific instrumentsin the April issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE IVORY FOXHOLE

October 1976 By JEFFREY HART -

Feature

FeatureMENAGE A HUIT

October 1976 By ROGERS E. M. WHITAKER -

Feature

FeatureRED BALLING IN THE JERSEY NIGHT

October 1976 By Jeffrey Brodrick -

Feature

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL -

Article

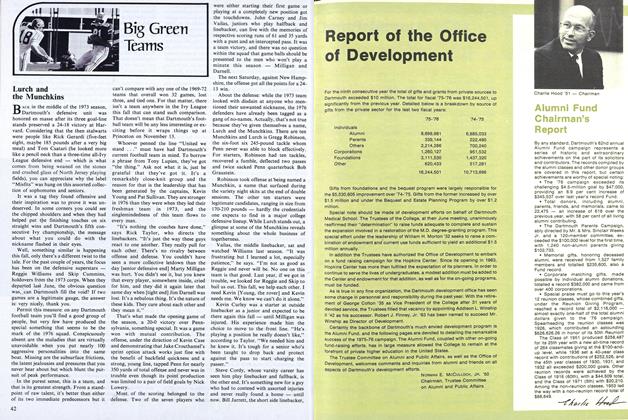

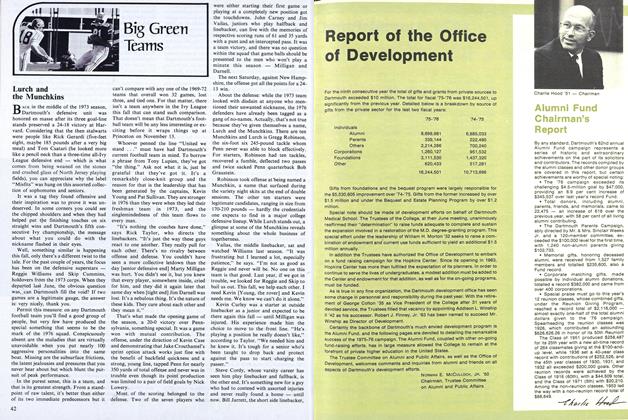

ArticleAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

October 1976 -

Article

ArticleLurch and the Munchkins

October 1976 By JACK DEGANGE

ALLEN L. KING

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

December 1976 -

Books

BooksCOLLEGE PHYSICS

July 1960 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Names on the Moon

MARCH 1971 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

ArticleThe Toppled Towers of Wilder

JUNE 1973 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureTHE 18th century highboys of Benjamin Randolph's

April 1976 By ALLEN L. KING

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE BARRETT CUP AND MEDAL

-

Article

ArticleANNOUNCE AWARDS FOR YEAR

August, 1925 -

Article

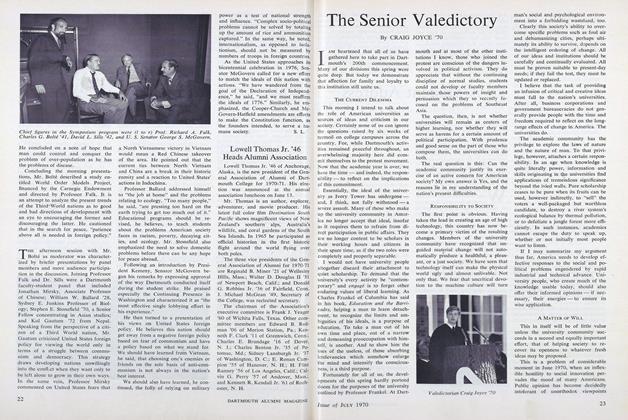

ArticleLowell Thomas Jr. '46 Heads Alumni Association

JULY 1970 -

Article

ArticleSo Does the N.E.H.

December 1995 -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

March 1944 By E. Quillian Brazel USNR. -

Article

ArticleTHE BONDS OF COMPETITION

MARCH 1997 By Moira Redcorn '88