Nathan Smith Professorof Medicine

By any measure, they are long leaps from the flatlands of mid-American corn country to the world's craggy rooftops of the Himalayas and the Andes.

Yet these are the strides taken by Dr. S. Marsh Tenney "44, son of a Bloomington, Ill., farm manager whose omniverous curiosity has proved a magic wand in a career transporting him periodically to some of the farthest and highest reaches of the world. That curiosity, combined with an orderly mind and a great capacity for work, also has made him, as much as any one. the personification of today's Dartmouth Medical School.

Symbolic of his achievements, in medicine and for Dartmouth, is his recent appointment to the Nathan Smith Professorship, named in memory of the physician who founded the Dartmouth Medical School 177 years ago.

In part because of the model of a family doctor in Bloomington, in part because of the remarkably catholic library which his parents had acquired for their home, Tenney decided early that he wanted to become a physician. On the basis of his wide-ranging reading as a youth, he refined that goal to the study of physiology, which seemed to him then as now to be at the heart of the science of man. And because he liked what he read about New England, he decided he wanted to go to college there. Something of a loner and a country boy, he added a condition that he only wanted a college removed from the city.

Although Tenney had never been in New England, he zeroed in on Dartmouth as his choice, applied and was accepted in the Class of 1944. A year after he matriculated, the United States entered World War II and classes at Dartmouth were accelerated. He didn't mind the pace.

Within two years, he had completed his pre-medical requirements - and had taken all the courses offered in Chinese language and literature, a continuing intellectual avocation. Accepted by the Dartmouth Medical School before his third, or senior, year in college. Tenney completed the medical program one year after graduation, going on to Cornell for the M.D. degree.

After an internship and assistant residency in medicine at Strong Memorial Hospital at the Rochester School of Medicine, he was called to active service in the Navy. In one of those welcome instances when the military takes note of a man's whole record, the Navy recognized his knowledge of Chinese and assigned him to Shanghai as the chief medical officer for the naval installation there. In two years, he packed in a decade of practice treating not only the naval detachment but also American merchant marine crew passing through, American and foreign consulate personnel, retired Navy men and their dependents, and a colony of Sikhs whom the British had employed to police that Crown Colony. In addition, he also agreed to provide medical care for the monks at a nearby Buddhist monastery in exchange for tutoring in Buddhist philosophy.

When Communist Chinese troops took Shanghai, Tenney returned to the faculty at the University of Rochester. A year's stint (1950-51) in Hanover as a teaching fellow kept him in Dartmouth's sights, and five years later he accepted an appointment as Professor of Physiology and chairman of a new department at the Dartmouth Medical School.

As a specialist in the study of how humans and other animals utilize oxygen and how they adapt to low oxygen supplies, either as a result of environment as at very high altitudes, or of disease, he is the author of more than 100 papers and is regularly invited to discuss his work at national and international professional meetings.

While the majority of Tenney's research is done in his laboratory at Dartmouth, his work also takes him periodically to the Himalayas and the Andes. The South American mountain chain is the "richest" living laboratory for his research, he says, because there millions of Indians, descendants of the Incas, have lived for generations at elevations of 15,000 feet, having adapted completely to an atmosphere containing about two-thirds the oxygen present at sea level. At other times, his research into the mechanics of short-term adaptation to low oxygen supply has also taken him to sea level in the Caribbean area to study the manatee.

"I became interested in the vital role of oxygen in the economy of mammals a long time ago," Tenney explains. "The responses to deprivation of oxygen, either as a result of diseases of the heart, circulatory system or lungs, or because of the environment, are at once the result of the most primitive and the most sophisticated control systems of the body. The ways animals adapt, both on short- and long-term bases, provide clues to the evolution of essential survival systems. We are oxygen dependent. But it was not always so. Life evolved at a time when there was no or little oxygen in our atmosphere. But in the long, long history of life, as the environment has changed so have living organisms and now the highest forms of life have only remnants of mechanisms enabling them to function without oxygen. As a result, any deficiency in oxygen threatens to compromise function, and physiological regulatory mechanisms are necessary; the brain especially is dependent on a steady supply."

Tenney explains how whales and other diving mammals have developed a short-run oxygen conserving mechanism, which, when they are under water, directs the oxygen in the body only to the lungs, heart and brain, enabling those species to survive their long dives without mortal injury or crippling damage. But the long-term adjustment to low oxygen is of greater interest to Tenney, and here man is most instructive. The large populations that have made an entirely satisfactory accommodation to high-altitude environments demonstrate many highly sophisticated adaptations, but for the majority, the best mechanisms remain obscure. And there are limits. No society has been able to sustain itself long in the thin air over 18,000 feet. "Interestingly enough," he says, "it's been found that the mountain climbers brought up near sea level make about 90 per cent of the functional adjustments necessary to high altitude existence in four to six weeks of acclimatization, which explains how men have been able to climb the 29,000 feet to the top of Mount Everest without oxygen masks."

Beyond his research and his teaching, Tenney has found time to serve as a prime mover in the recently completed expansion often described as the "re-founding" of the Dartmouth Medical School.

In his initial appointment, he also was named Associate Dean for Planning and Research and charged with organizing the first phase of reconstituting the medical school. In 1956. when he arrived, the school had an eight-man faculty offering a two-year program in basic medicine to a student body of 48. In 1957, he was named Director of Medical Sciences and his responsibilities included recruiting a faculty, planning new physical facilities, developing a new educational program and leading a fund raising effort to make it all possible In 1960, he was appointed dean for the first time. When Tenney returned to full-time teaching and research in 1962, the faculty has been nearly quadrupled, the student body expanded to 100, and an entire new complex of buildings planned and under construction. And he had taken a decisive role in raising $8 million toward a $10 million "refounding fund."

He took the reins of the school again in 1966, serving as acting dean for nearly a year until the appointment of Dr. Carleton B. Chapman as the dean who subsequently implemented restoration of the M.D. degree after a lapse of more than 50 years. Chapman resigned early in 1973 to become vice president of the Commonwealth Fund, and Tenney responded for a third time to the call for his administrative help, serving again as acting dean for several months. During this time, the school did not miss a step in continued development of its three-year M.D. program, now widely recognized as a model in efficient curriculum organization, in its expansion toward its goal of about 200 students, and in construction of the Vail Medical Sciences Building which doubled the school's teaching and research facilities.

He returned to his teaching, research and departmental concerns last July with the appointment of Dr. James C. Strickler '50 as dean.

Tenney's appointment to the Nathan Smith Professorship was applauded by President Kemeny as an instance of "historic justice.'' Recalling Tenney's role through the two decades that have given the Dartmouth Medical School its modern dimensions, Kemeny said, "His leadership, uncompromising dedication to quality and his constancy can be seen now as having provided the continuity and direction essential to the success of what we've called the 'refounding' of the school. It is therefore entirely fitting that, in his academic title, he be linked formally with the name of that earlier physician of great creative energy who founded the school in 1797 - the fourth established in the then young nation."

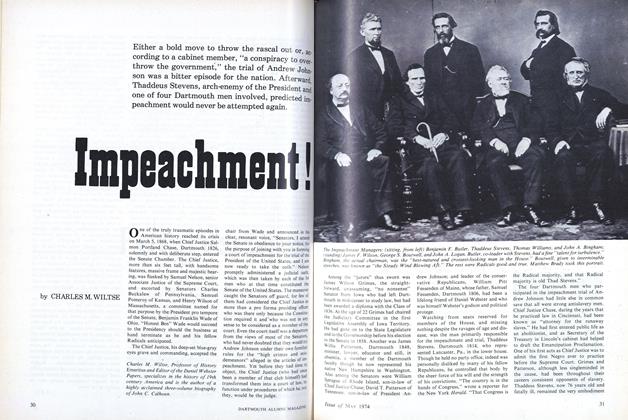

Marsh Tenney and an Andes villager.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleHEINZ VALTIN

February 1974 By Andrew C. Vail Memorial, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleEndowed Professorships

MARCH 1973 By R.B.G. -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleJAMES BRIAN QUINN

December 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleLAWRENCE E. HARVEY

January 1975 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleBenjamin Ames Kimball Professor of Administration

March 1975 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleCLASS OF 1892

June 1916 -

Article

ArticleSTATISTICS OF THE DARTMOUTH FACULTY

March 1917 -

Article

ArticleWeekly Luncheon Dates for Alumni Clubs

June 1934 -

Article

ArticleFree Will and the Virgin Spring Principle

January 1977 -

Article

ArticleWriting Against The Crowd

April 1977 -

Article

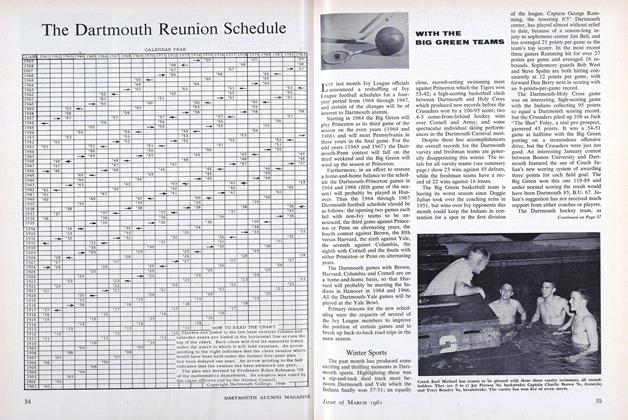

ArticleWinter Sports

March 1961 By CLIFF JORDAN '45