WAYS OF LIGHT

by Richard Eberhart '26 Oxford, 1980. 68 pp. $11.95

SURVIVORS by Richard Eberhart '26 BOA Editions, 1979. 16 pp. $2

For Richard Eberhart, Dartmouth's poet-in- residence, this year, 1980, marks a notable aniversary. He published his first book of poems, A Bravery of Earth, in 1930. Now, 50 years later, Survivors (1979) and Ways of Light (1980) are respectively his 20th and 21st volumes of verse.

Half a century in the public eye is a long time, long enough, surely, to earn and to savor the many honors that have come his way, but also long enough to generate some hazards. Even now one of them looms. It is a hazard engendered by success, to be sure, the kind many poets would sell their souls to have to face. Nevertheless, the awful truth is that Richard Eberhart is in some danger of becom- ing a poetic institution.

From the graduate schools to the book reviews the news is very grave. The process of institutionalizing began, as it always does, with anthologizing, and for several decades, of course, most anthologies of modern poetry have included generous selections of Eberhart's work. It gained momentum when, several years ago, a major and very good book on Eberhart was published, which in turn has been followed by several more specialized, monograph-length studies of the poet and his art. Clearly, the critics have begun to swarm.

Even more ominously, students have recently begun to commit bibliographies, those stupefy- ing lists of not just the poet's publications but of half-a-century's-worth of reviews and articles about his work as well. And now, ap- propriately, there comes that venerable academic rite the festschrift. Sometime this fall, perhaps by October, the New EnglandReview will have published a festschrift on the work of Richard Eberhart. The portents por- tend, the signs forebode. There remains only that ultimate menace. And somewhere, I have not the slightest doubt, he or she sits this very minute deep in the murky stacks of some uni- versity library, that academic deus ex machina: a Ph.D. candidate contemplating a disserta- tion on "The Poetry of Richard Eberhart."

Perhaps the transmogrification of the flesh- and-blood poet into a bloodless poetic institu- tion is inevitable. Perhaps, as Auden suggested of Yeats, every successful poet sooner or later becomes his admirers. Perhaps not. Whichever way it goes, Ways of Light seems destined to become a key book in the Eberhart canon. It is in many respects a capstone volume, a representative book which has been, so to speak, 50 years in the making. It is almost as if the poet were deliberately using Ways of Light as a summing-up.

It demonstrates, for example, that many of Eberhart's poems are, to an unusual degree, autobiographical. This occurs in part because, contrary to much other modern poetic usage, the persona, the"I" who speaks an Eberhart poem, is seldom a fictive speaker constructed by the poet to serve the dramatic purposes of that particular poem. More often than not, it rather seems Richard Eberhart, the poet the man himself, unmediated. Thus comes about that direct, autobiographical effect we have come to associate with an Eberhart poem. Ways of Light demonstrates, too, Eberhart's wit. Turn, if you will, to the small poem "Coloma." But be warned: First you should read a rather lugubrious little poem by Robert Frost called "Nothing Gold Can Stay." Otherwise, you might miss all the fun as Eberhart stands Frost's poem precisely on its head, gold and all (and throws in a pun to boot). And Ways of Light demonstrates the range of Eberhart's craftsmanship. It can be put this way: He is the only poet that I, at least, can recall who has successfully used the word "eleemosynary" in a poem. And that takes some doing!

Above all, Ways of Light demonstrates that Eberhart is a philosophical poet. (If "philosophical" seems a shade too solemn for this smiling public man, "ruminative" will do almost as well.) In "A Snowfall' he'sums it up neatly in two lines: "There is something in me to test nature,/To disallow it the archaic predominance." Precisely so. Is that not what Eberhart has been doing lifelong and in a hun- dred different metaphors: "testing" nature? Testing in the sense of probing, questioning, hypothesizing, speculating. Is there anything out there? he asks. Any order to be imposed on apparent chaos, any meaning in apparent meaninglessness, any certitude, or joy even, or peace, or help from pain?

Yes, answers the poet in one mood, con- fidently: "I now make my predicament equal to nature's./I have the power, although it is timed and limited,/To assert my order against the order of nature." Like every creative act, the very act of writing a poem is itself the imposi- tion of human order on natural chaos. It is, as Eberhart says, an attempt "not to let nature better us,/But to take this softness and this plenitude/As aesthetic and control it as it falls." But in another, more somber mood the confidence vanishes; nature appears only as eternal flux, not just the unknown but the un- knowable: "No ebb, no flow not subject to change,/No changelessness in our con- sciousness/Remaining, nothing but what Heraclitus told."

Even so, the poet still praises what he cannot fathom. He hears the primal shriek of an even- ing loon across stilled waters, "strange, palpable, ebullient, wavering,/A cry that I can- not understand,/ Praise to the cry that I cannot understand." And where praise is irrelevant, there is acceptance. In the final poem of the book (entitled, significantly, "Learning from Nature") the poet watches a bird which has been momentarily stunned from having flown headlong into a glass door. The poem concludes this way: The bird suddenly flewOff into the darkening afternoon.He did not say how he was.He was stopped, and he went on.It taught me acceptanceof irrationality,For if he or we could see betterWe would know, but we have to go on.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

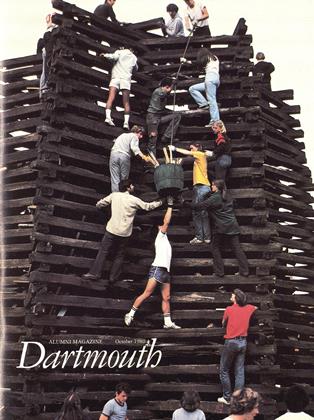

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

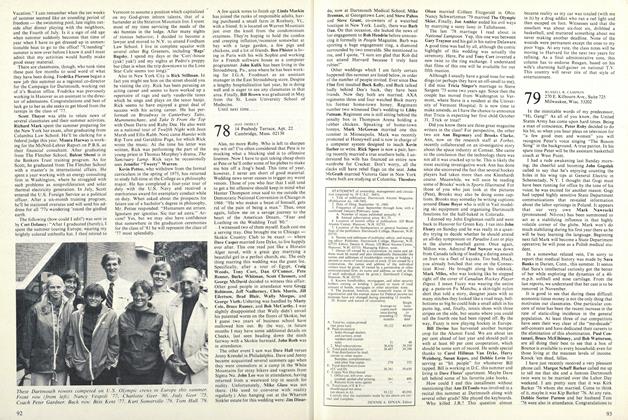

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

R. H. R.

-

Article

ArticleNotes on a Distinguished Defendant and the Supreme Court’s Great non-decision

DEC. 1977 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksTight Little Murder

December 1978 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksIntolerable Ambiguity

November 1980 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksWood Butchers

June 1981 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksSleuthing

APRIL 1982 By R. H. R. -

Books

BooksMan in the Cambric Mask

JUNE 1982 By R. H. R.

Books

-

Books

BooksNotes on medieval beasts and the versatile writer who modernizes them, and memorials for a Dartmouth organist.

March 1977 -

Books

BooksGEORGETOWN HOUSES OF THE FEDERAL PERIOD,

March 1945 By Hugh Morrison '26. -

Books

BooksINTERVIEWING COSTS IN SURVEY RESEARCH.

FEBRUARY 1965 By JOHN ADLER '49 -

Books

BooksSHOCK METAMORPHISM OF NATURAL MATERIALS.

APRIL 1969 By JOHN B. LYONS -

Books

BooksSquaring Off

October 1976 By KATHLEEN P. MORIARTY -

Books

BooksTHE ART OF SKIING. N. Y

March 1933 By N. L. Goodrich