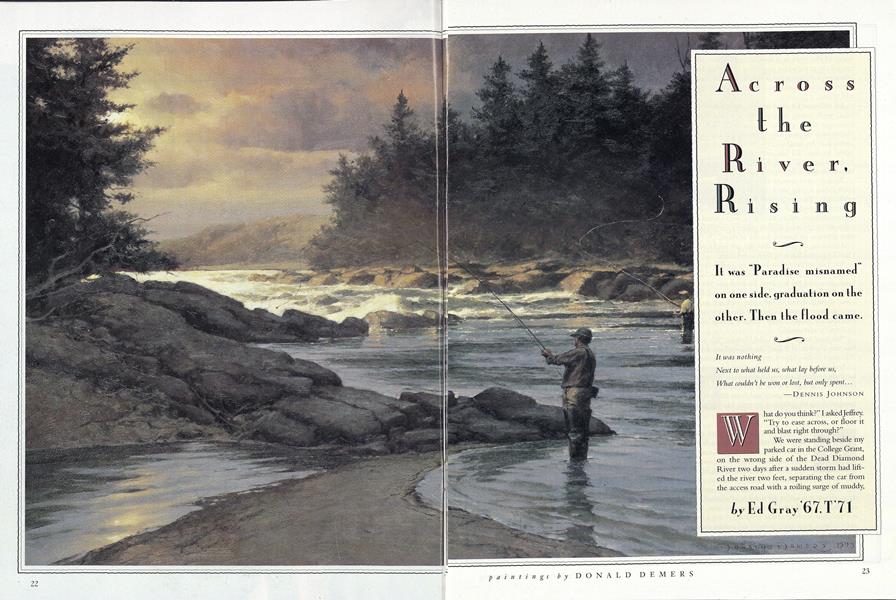

It was "Paradise misnamed" on one side, graduation on the other. Then the flood came.

What do you think?" I asked Jeffrey. "Try to ease across, or floor it and blast right through?" We were standing beside my parked car in the College Grant, on the wrong side of the Dead Diamond River two days after a sudden storm had lifted the river two feet, separating the car from the access road with a roiling surge of muddy,

downhill water. Hour by hour in those two days we'd watched the river as it had inched fractionally back toward the graveled set of purling shadows it had been when we'd driven across it the day we'd arrived. Now it was time to go, and the current remained high, fast, and strong.

Jeff Hills and I looked at each other, letting the situ- ation work its way through. We were four days away from our third graduation together: high school, Dartmouth '67, and now almost Amos Tuck. I'm pretty sure he laughed first, but it was close. "Yeah, right," he said. "I'll take pictures."

It was June 1971, and that was a much better answer than it seemed at the time.

We had come here, to the old North Camp at Hell Gate Falls, with a week to kill between exams and graduation. We were 26 years old; behind each of us lay 19 years in scheduled schoolrooms and two years under written military orders, all of it focused toward obtain- ing a standard series of very specific certificates. We were about to be handed the last of them.

Assuming, of course, that we got back across the Dead Diamond River in time to get there.

The trip to the Grant had been godmothered the previous winter by Jeff's wife, Marion, who had fallen hook, line, and Mickey Finn for Professor Herb Hill's pokerfaced tales of unmolested northern wildlife that came nightly down to the river to drink and frolic among hungry trout in front of the rarely occupied cabins of the North Camp. "The Hell Gate,'" he'd said, "is Paradise misnamed."

"We have to go there," said Marion. "It's got to be like the Garden of Eden." In the darkened sulks of Hanover's endless March, there was no coherent retort.

And so in June we went, the three of us taking the long drive north through an almost finished New Hampshire spring. With us in another car were Tuck classmates John Hemingway and Scott Philbrook, who brought along his girlfriend, a nurse. Marion was eight months pregnant.

S SOCIAL SECURITY AND THE ARCTIC A National Wildlife Refuge do for every American, the College Grant adds dimension and promise to the unfinished lives of all Dartmouth graduates, even those whose plans include its specific avoidance. Perhaps especially those, for the development of one's individuality is only as genuine as the number of selected paths is outnumbered by the ways not taken. For what, after all, is a first-rank undergraduate program if not a maze of open courses, beckoning liberally and artfully signposted by those who have gone before? And, as most of us assume before we get here, a good number of those paths that begin in Hanover have always been green.

Not that Jeffrey and I had trod many of them, however. Our separate but comparable paths through both Dartmouth and Tuck had been least-resistant all the way. His unscheduled two-year hiatus came after we were sophomores while mine waited until between halves at Tuck School, when graduate-student draft deferments were peremptorily erased by the peaking body counts in Vietnam. Jeffrey had, by then, finished his active tour in the Marine Corps and was back at Dartmouth, trailing me by the two years I was about to spend as a naval officer in Norfolk, Virginia. We caught back up with each other for that last year at Tuck.

In our variegated wanderings during those eight years when one or both of us had been enrolled at Dartmouth, neither Jeffrey nor I had ever set foot in the College Grant. It had been there for us, of course, and we both had known it. Like certain corners deep in the Baker stacks, we just hadn't gone there yet. And like the books on those shelves, the revelations of the Dead Diamond River lay self-contained and waiting, indifferent to even the probability of our approach.

But approach we did, finally and as a sort of let's-tryit, we-don't-want-to-have-missed-something reflex at what was certainly the end of our full-time association with Dartmouth. Through the Gate Camp entrance we drove, expecting nothing in particular and every- thing in general.

That's pretty much what we found.

The College Grant is big enough so that if you used it to overlay them, it would cover the downtown parts of Hanover, Lebanon, and White River junction like an evergreen blanket. With a population of zero. The single dirt road meandering north through it from the entrance up to Hell Gate is almost identically the distance from the Hopkins Center to the Skiway, if you can imagine that drive as a winding rough track through unbroken white pine, spruce, alder, hemlock, and wild raspberries. No Dartmouth campus, Med School, stop lights, fire department, Pat & Tony's, Chieftain Motel, Fullington Farm, Lyme Common, or long, smoothly paved 55-mile-an-hour Route 10 straightaways. No Hanover cops with radar. Just the long, quiet sweep of the northern forest, the crunch of gravel under your tires, and an occasional sparkling blue glimpse of the Dead Diamond River, flowing south.

It is by anyone's definition the big woods, especially so when you realize that when you are there you are already deeply into a nearly unbroken series of timbered parcels stretching from Vermont to New Brunswick. The College Grant has borders back in its hills but the trees don't know them, the wildlife doesn't

honor them, and you can't find them. Stay near the road, they had told us as we showed them our vehicle permits back at the gate camp.

Or near the river. It was June, the best month of the year for brooktrout fishing. Jeffrey and I had brought our fly rods and waders. In the

water was where we'd be, and all the way up the access road we marveled at the unbroken riffles and rocky pools of the Dead Diamond.

Today there are two newer log cabins at the Hell Gate, one on each side of the river, but when we drove up to the turnoff back then there were just the old greenpainted frame shacks of the North Camp, and they were across the river from the road. A cable-hung, plank-slatted footbridge swayed its catenary way over the sliding water below it, while beyond, across a highgrass field, a winding muddy path angled uphill to the cabins themselves, 200 yards away. The six of us got out of the two cars and checked it out.

The bridge builders had wisely selected a narrow, high-banked section of the river over which to hang it, but the tradeoff was that long walk on the other side to get to the cabins. Ultralight packing hadn't been on our minds back in Hanover, as the multiple corrugated cartons of canned food and bottled beverages in the cars attested. We stood there looking at the bridge, at the long, awkward path on the other side, and then we looked at Marion.

"Hey," she said. "I can cross that." We looked back at the bridge, and at the ten-foot drop below it. "Let's drive up a ways. See if there's another way," I said.

There was, a hundred yards up a steep littie turnoff from the road that slanted directly down and into the river, which was only 30 feet wide, gravel-bottomed and shallow. And on the other side, leading directly to the cabins, was the unmistakable contour of a twotrack road coming right out of the river across from where the little turnoff went in.

We didn't even hesitate. With Jeffrey and Marion in- side, I drove the Chevy wagon across. The deepest part was only 18 inches, and others followed in John's van.

With at least an hour's packing and hauling saved by the simple expediency of driving across the river, we were in high spirits as the last of the gear was stowed in the cabin. It was two o'clock on a windless, crystalline afternoon and Jeffrey and I decided it was time to find the trout.

"Move the cars back across?" asked John as we started to go.

"Nah" I said. "Just have to bring 'em back to pack up at the end, right?"

That not one of us, there at the fully accelerated apogee of our academic learning curves, thought to raise the obvious objection to this plan seems only a little sillier to me now than it probably would have then, had it even occurred to me as Jeffrey and I went out with our fishing rods in hand, moving upstream and heading in the warm, mid-afternoon sun toward the unseen storm to come.

NE OF FLY FISHING'S FIRST LESSONS IS that the trout are always facing upstream, watching ahead for whatever is coming while holding their own position in the current. That they can see you, too, as you stand in the stream angling for them, is axiomatic. The solution is to stand behind them and cast upstream to where they lie, but this takes some skill to do properly. An alternative for the less capable is to crouch upstream some distance from a likely location and swing a wet fly on a long line down and across the current near the unseen fish. Success that way is more a function of luck and quick reaction, requiring less talent but some concentration.

That's what I was doing, a mile or so from the cabins and around a bend from Jeffrey, when the lightning struck.

What's the loudest noise you've ever heard? No, this was worse. This was incomparable, in the

way that a sudden, single, top-of-the-lungs scream in your darkened, quiet bedroom would jolt you heart-stopped awake more than 100,000 fullvoiced football fans ever could.

The rain and wind hit a half-second behind the thunder-cannon, slamming me from behind and lifting instant showering wavelets up and off the stream around me just as surge after surge of hard, wind-driven pellets of rain slashed in sheets through the instant darkness; Lightning and thunder came strobe-lit and constant, inseparable, and in the woods on either side of the river trees began to fall, cracking and popping as the wind pushed them down faster than gravity could ever have alone.

In the middle of the roaring, hissing, pounding barrage, as bolts of lightning struck almost constantly in all quadrants, I was standing knee-deep in running water. But on both Sides of the river trees were slamming down in darkness and at random everywhere around me. Fear feeds on helplessness, and mine was intravenous, numbing. Complete.

And then it passed, rumbling and bumping down the valley, leaving behind a darkened and dripping world of angular and broken spruces on either side of the river that still came past at the same height, but now flowing like flattened and dented pewter, surface gray as if its internal lights had been turned off.

With shivers that ran completely through me, I moved unsteadily downstream until I found Jeffrey, speechless, in the water and moving up to look for me. When the blast first hit, a huge spruce had gone down on the bank right beside him. It lay there in the deluge still hinged with green wood to the stump where it snapped, and Jeffrey had climbed out of the river and gotten under the natural shield as other trees came down all around him. Together we headed back, walking on the road and stepping over and around the scores of trees that now lay across it.

The others had, of course, been inside the cabin, feet up around the woodstove, listening to the rain on the roof while the storm eased past. It had mellowed

by the time it had got there, and no trees had gone down, as Jeffrey and I could see in the deepening evening gloom when we reached Hell Gate. We came inside to the woodstove warmth and Coleman glow, and the story was in our eyes.

While we told it, outside in the darkness the river began to rise.

By morning, when we walked down to stare at it, our clever little fording place was now a doubled-in-width, sliding brown torrent of turbulent water that none of us dared walk partway into, let alone all the way across.

"Think it'll go down in time?" Scott asked.

"Going to find out," said John.

With no option, we waited, watching the river in the fine weather of the next two days and making little rock cairns on the bank to mark its receding progress. The day of departure came, and our now very careful monitoring of the water level told us that there was more water than when we first crossed, but we differed on exactly how much. We hadn't, after all, taken an initial measurement.

"You can make it," I said. "Let's go."

"You first," suggested John.

We loaded the cars, moved mine down to streamside, and that's where we were when Jeffrey climbed up the bank, ready to take pictures. Marion eased into the front seat beside me and made a face at him. "I trust you, Ed," she said. "Let's go."

I put it in gear.

Now. Do you need to know what happened? How or if we made it across? Does it specifically matter whether or not our feet got wet, or if our cars got stuck, or that Lucinda Hills is now a junior in college? That her father and I still go walking in rivers, sometimes together? No. I don't think so. I think it only matters that we were there. And that it was then.

Things were rising. Unseen swirls lifted beneath us and we were gone with them, sliding downhill toward consequences.

We looked at ike bridge, at the awkward palk on ike other side, and then we looked at Marion.

Marion eased into ike front seal. "I trust you, Ed, she said. Let's go. I put it into gear.

It was nothingNext to what held us, what lay before us,What couldn't be won or lost, but only spent... —DENNIS JOHNSON

ED GRAY, the former founding editor of Gray's SportingJournal, is a writer in Lyme, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

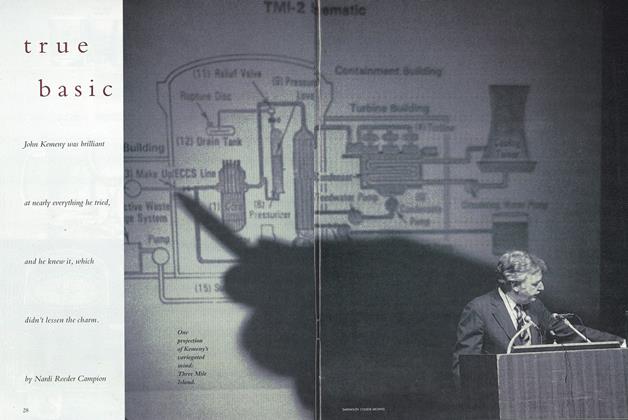

Cover StoryTrue Basic

May 1993 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

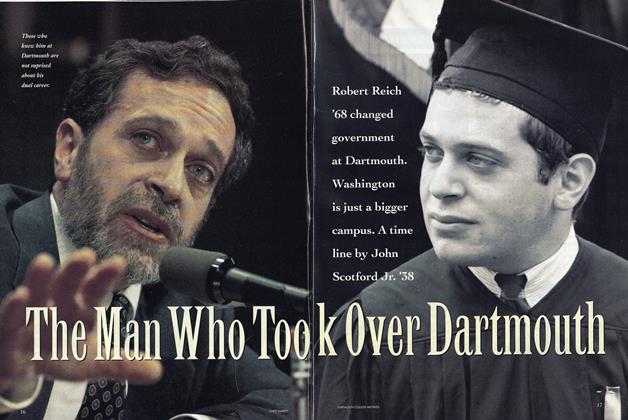

FeatureThe Man Who Took Over Dartmouth

May 1993 By John Scotford Jr. '38 -

Article

ArticleWomen in Love

May 1993 By Katharine Gingrass-Conley -

Article

ArticleA Postponed Power

May 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1993 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

May 1993 By Rick Joyce

Features

-

Feature

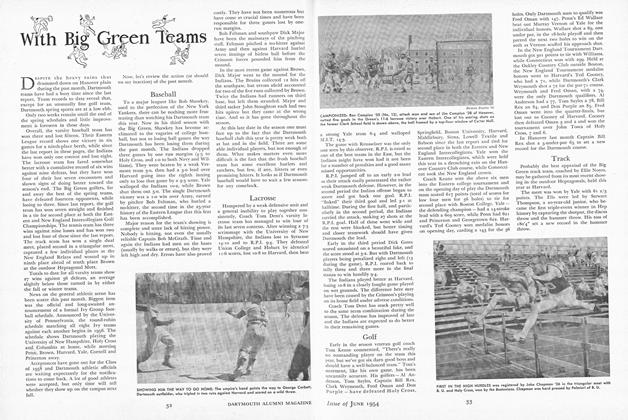

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureInternational Catalyst

FEBRUARY 1967 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1971 By B.B. -

Feature

FeatureKenneth Allan Robinson

February 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Feature

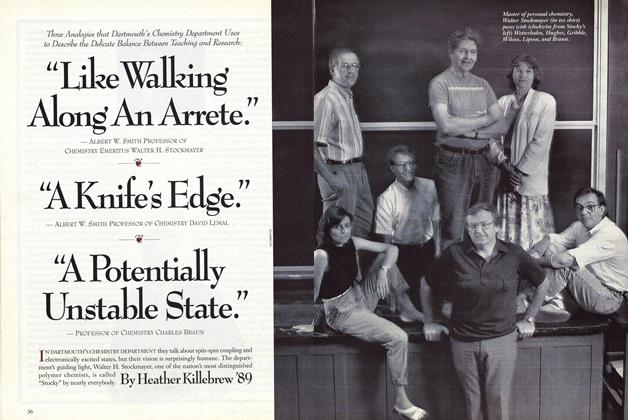

Feature"Like Walking Along an Arrete."

OCTOBER 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Cover Story

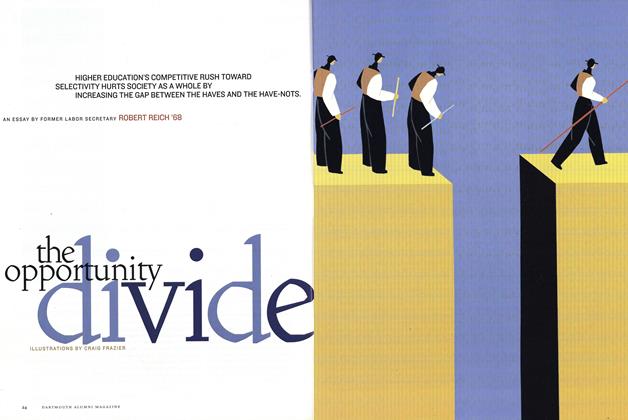

Cover StoryThe Opportunity Divide

Mar/Apr 2001 By ROBERT REICH ’68