For The Life of Arthur Young 1741-1820 (727 pages, American Philosophical Society, $10), John G. Gazley, Dartmouth Professor of History, Emeritus, on five counts gets about as high praise as is ever offered in the London Times Literary Supplement. His is a four-column and major article of December 28, 1973 and runs over to another page. It is very long. The critic does not point out minor flaws to flaunt his own erudition. The praise for American scholarship and an American scholar is rare and unusually high. Samples: (1) "Dr. Gazley has spent many years in an exhaustive search for Young's private papers, and he has finally produced a fascinating account of an extraordinary career and a most striking character." (2) Young "was undoubtedly one of the leading innovative spirits of an enormously innovating age. All this, and much more, appears in Dr. Gazley's richly documented and vastly interesting biography. Here we have at last an authoritative and definitive study of one of the key figures of the classic 'agricultural revolution'."

Do you know how Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) upset artistic critics and outraged the middle classes and all other classes as well? If you don't, Kynaston McShine '58, Curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, will tell you. He and Anne d'Harnoncourt, Curator of Twentieth Century Painting at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, are the editors of Marcel Duchamp, a volume of 360 pages and 429 illustrations, 12 in color, with 10 original essays by eminent scholars and critics covering his explorations in the areas of language, poetry, the machine, alchemy, the milieux, his friendships, and life style. Included are passages from his lectures, comments by more than 50 colleagues and friends, documentary illustrations, a chronology, and a bibliography. Costing $25, the volume is published jointly by the Museum of Modern Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Baffling and tantalizing was the problem facing McShine in writing "La Vie en RRose," his nine-page essay. Marcel Duchamp was a dandy, amateur, inventor, aristocrat, generator, punster, avant-garde figure, and symbol of modernism. Repudiating all categories, he plunged into whatever was most appropriate for him at a given moment: poetry, linguistics, optics, film, theater, music, and bookmaking, and he delighted in the use of diverse and unorthodox materials, like dust silver, talcum powder, marzipan, and his own head. As McShine points out, Duchamp's work is un-paraphrasable and untranslatable, for he created his own language, constantly mocked conventions, kept warring with himself, renounced good sense, despised the facile, transcended all artistic rules, repudiated "the stupidity of the painter," and kept reiterating that art ultimately is not rational but mystical. In consequence, McShine is forced into paradoxes. Duchamp turns himself into myth. His strategy proposes the life of chance, converted it into power, and it changes life into art and art into life. Follwing Mallarmé, his law is to paint not the thing but the effect it produces. Fascinated by chess, he played it by cable and used a complicated code to play two games simultaneously. The chessboard was paradise, "the landscape of the soul," and the universe.

Ever since 1913 when Nude Descending aStaircase so startled and outraged the bourgeoisie at Armory Show in New York the elusive creativity of Duchamp has profoundly influenced modern art, and his impact on the twentieth century is almost as great as that of Matisse and Picasso.

In another 40-page publication also entitled Marcel Duchamp, prepared by Anne d'Harnon-court and Kynaston McShine to serve as a guide for the Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago exhibitions, in the design of the cover another Dartmouth man, Rudi Blesh '21, comes into play. In 1956 Duchamp designed a cover for the book Modern Art U.S.A. by Professor Blesh, which the publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, is reported to have rejected as a "bad joke" It seemed appropriate for Editors d'Harnoncourt and McShine to adopt Duchamp's unused Blesh design to clothe a publication for the three exhibitions. Not surprisingly, the cover is a neat visual pun on the idea of a book jacket, using the front and back view of a tailcoat (Jacquette in French). The image also reflects Duchamp's fascination with the relation of outer form to inner content ("clothes make the man").

Pack-rats, aren't we all? No? Then, chip-munks But they dwell in the future, hibernate, and lose all interest in the past. In squirreling away our memories as collectors, we dig into the earth of our past for the acorns that still have germinating power. The acorns take various forms. Postage stamps may be the most common. The more peculiar, the more fun. Avon bottles that fetch perfumed prices; old wine catalogues; old motor cars more delicate than Swiss watches.

A collector of old opera and dance band records, with research overtones, Dick Holbrook '31 concentrates on jazz of early days. His deepest probe is an article, "Our Word Jazz," Storyville, Dec. 1973/ Jan. 1974.

Dick Holbrook is eager to pinpoint the earliest use of the word in connection with music. Why the italics? Because around 1900, in some circles, jazz was a slang word for coitus The word may have derived from gism or jasm, early Americanisms that carried the meaning of energy and enthusiasm. One researcher in New Orleans thinks the word derives from references to prostitutes as jezebels (pronounced like jazz-a-belle). In their flair for picturesque speech, the Irish there combined profanity and obscenity with a nice transference. "Be-Jesus," pronounced be-jayzz, referred to the sex act.

As a description of music, Dick Holbrook quotes television comedian William Demarest who recalls vaudeville days in 1910 at the Per-tola Theatre in San Francisco. He and his brother George had a cello and violin song-and-patter comedy routine. They were playing the Grizzly Bear Rag. "George turned to me and said, 'Come on, jazz it up.' " In March. 1913. the word jazz first appeared in print. "Scoop" Gleason, sportswriter for the San Francisco Bulletin, used it in a dozen stories as a synonym for peppy. Example: "Henley the pitcher put a little more of the old 'jazz' on the pill."

Until 1913 everyone seemed to have heard the word from everyone else. The word was as Ernest J. Hopkins, a 1913 San Francisco columnist, observed, "New, long-needed, satisfactory sounding, peppy, versatile, like the crackling of a brisk electric spark." The work surfaced musically in late 1914 and 1915 in Chicago, and jazz bands then swept the country as an American art form.

Dick Holbrook jazzed it up, musically speaking, in the late 1920s at Dartmouth College, with his seldom-silent dormitory phonograph. As a New York advertising man. he was Peppy and versatile enough to publish booka on military, collegiate, and clerical subjects. His fourth, when ready for publication, will be titled Our Word Jazz, and he will concentrate on the early practitioners of that wonderful little four-letter word crackling like a brisk electric spark.

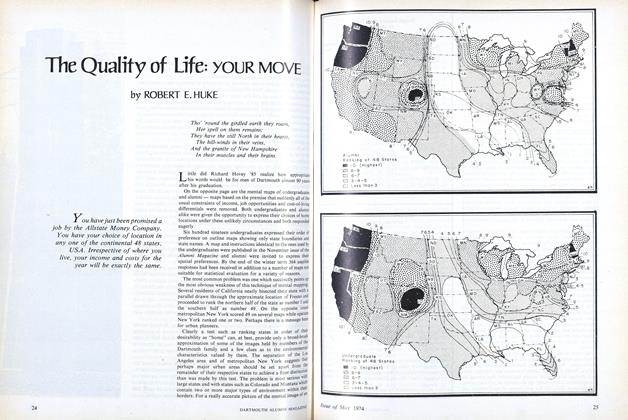

What's your problem? Identify its nature and then choose the statistical technique That's the strategy of Anderson's and Sclove's book IntroductoryStatistical Analysis, published by Houghton Mifflin Company (499 pages, $11.95). The authors, T. W. Anderson of Stan-ford university and Stanley L. Sclove '62 of the University of Illinois (Chicago Circle), organize statistical techniques according to the nature of the data and the nature of the problem. Their reasoning and explanations are not based on mathematics but on intuition, verbal arguments, figures, and numerical examples. In conscience, though high-school algebra is occasionally drawn on, little mathematical background is required. (Verbal and conceptual levels are higher than mathematical.) To aid students in understanding developments and how statistical analysis can answer interesting questions. examples are chosen from daily life and business, as well as from the different sciences, behavioral, life, physical, and engineering. Exercises of different degrees of difficulty touching on a variety of disciplines are thus scitable for undergraduutes in various majors. The book has been well tested. The manuscript was read and reviewed by 16 faculty members from various institutions, and five teaching assistants have made pedagogocal suggestions for improvement. The ten chapters are so organized that with possible strategic excisions they may be offered as a one-semester course, either terminal or as a gateway for further courses on statistical methods.

If there is anyone with a more expansive appreciation for Hempstead, Long Island, than Roger G. Allen '37, he will need bolstering with copy from leading American advertising experts to prove it. He is co-author and co-designer of Village of Hempstead Since 1643, bound in a patriotic blue. Profusely illustrated, it attempts to show how the village is the hub of Long Island, though so small an island hardly restricts Allen's expansive mood. It pervades chapter headings invigorating you with the euphoria of Hempstead and Allen felicities. Samples: "At the Hub of All Long Island: Gateway to a Thousand Pleasures," "The Mecca for Entertainment and Recreation," "The Complete Business Center," "The Hub of Higher Education," "An Attractive Tax Picture: Sound Fiscal Planning Provides Maximum Services at Lowest Cost," "Hempstead: the Complete Community," "A Great Place to Be: as Old Timer, Newcomer, or Visitor."

To give cherry-tree literalness and veracity to the facts contained within, the booklet cover produces the village seal showing a sketch of George Washington alighting from his coach in front of the old Sammis Tavern.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

J.H.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePORTRAIT OF PRESIDENT NICHOLS

May 1917 -

Article

ArticleHEROISM OF MONTGOMERY '15 SUBJECT OF GRAPHIC STORIES

March, 1922 -

Article

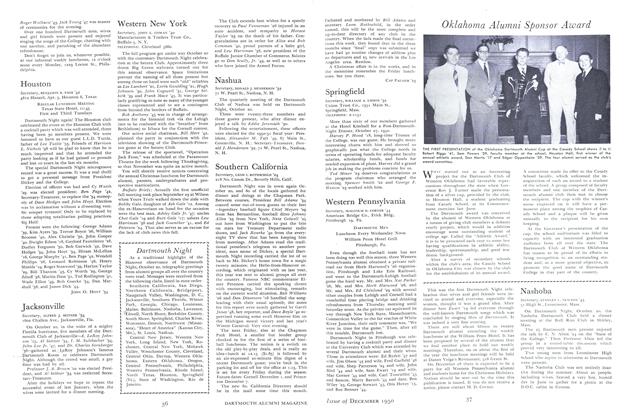

ArticleOklahoma Alumni Sponsor Award

December 1950 -

Article

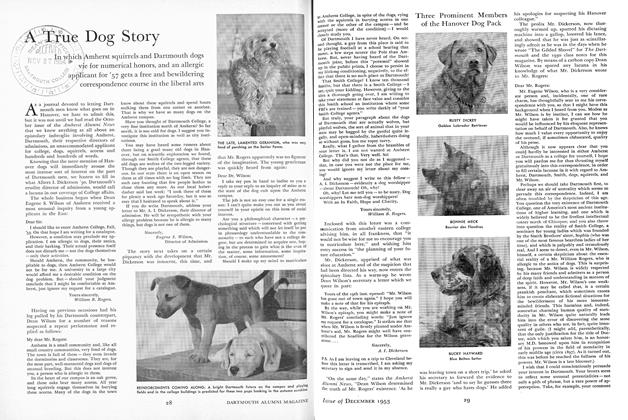

ArticleThree Prominent Members of the Hanover Dog Pack

December 1953 -

Article

ArticleCrossing the Green

APRIL 1986 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

February 1961 By PARKER MERROW '25