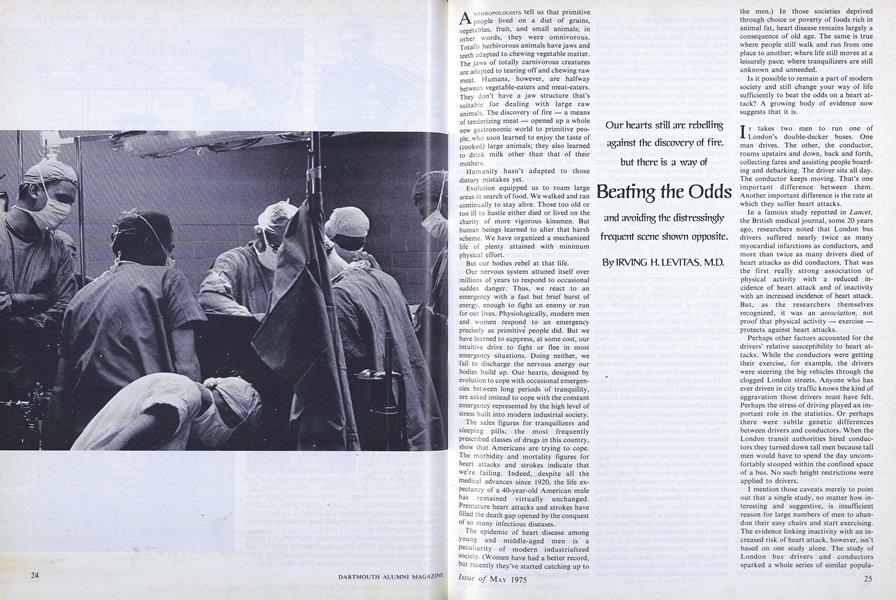

Our hearts still are rebelling against the discovery of fire, but there is a way of and avoiding the distressingly frequent scene shown opposite.

ANTHROPOLOGISTS tell us that primitive people lived on a diet of grains, vegetables, fruit, and small animals; in other words, they were omnivorous. Totally herbivorous animals have jaws and teeth adapted to chewing vegetable matter. The jaws of totally carnivorous creatures are adapted to tearing off and chewing raw meat. Humans, however, are halfway between vegetable-eaters and meat-eaters. They don't have a jaw structure that's suitable for dealing with large raw animals. The discovery of fire - a means of tenderizing meat - opened up a whole new gastronomic world to primitive people, who soon learned to enjoy the taste of (cooked) large animals; they also learned to drink milk other than that of their mothers.

Humanity hasn't adapted to those dietary mistakes yet.

Evolution equipped us to roam large areas in search of food. We walked and ran continually to stay alive. Those too old or too ill to hustle either died or lived on the charity of more vigorous kinsmen. But human beings learned to alter that harsh scheme. We have organized a mechanized life of plenty attained with minimum physical effort.

But our bodies rebel at that life.

Our nervous system attuned itself over millions of years to respond to occasional sudden danger. Thus, we react to an emergency with a fast but brief burst of energy, enough to fight an enemy or run for our lives. Physiologically, modern men and women respond to an emergency precisely as primitive people did. But we have learned to suppress, at some cost, our intuitive drive to fight or flee in most emergency situations. Doing neither, we fail to discharge the nervous energy our bodies build up. Our hearts, designed by evolution to cope with occasional emergencies between long periods of tranquility, are asked instead to cope with the constant emergency represented by the high level of stress built into modern industrial society.

The sales figures for tranquilizers and sleeping pills, the most frequently prescribed classes of drugs in this country, show that Americans are trying to cope. The morbidity and mortality figures for heart attacks and strokes indicate that we're failing. Indeed, despite all the medical advances since 1920, the life expectancy of a 40-year-old American male has remained virtually unchanged. Premature heart attacks and strokes have filled the death gap opened by the conquest of so many infectious diseases.

The epidemic of heart disease among young and middle-aged men is a Peculiarity of modern industrialized society. (Women have had a better record, but recently they've started catching up to the men.) In those societies deprived through choice or poverty of foods rich in animal fat, heart disease remains largely a consequence of old age. The same is true where people still walk and run from one place to another; where life still moves at a leisurely pace; where tranquilizers are still unknown and unneeded.

Is it possible to remain a part of modern society and still change your way of life sufficiently to beat the odds on a heart attack? A growing body of evidence now suggests that it is.

IT takes two men to run one of London's double-decker buses. One man drives. The other, the conductor, roams upstairs and down, back and forth, collecting fares and assisting people boarding and debarking. The driver sits all day. The conductor keeps moving. That's one important difference between them. Another important difference is the rate at which they suffer heart attacks.

In a famous study reported in Lancet, the British medical journal, some 20 years ago, researchers noted that London bus drivers suffered nearly twice as many myocardial infarctions as conductors, and more than twice as many drivers died of heart attacks as did conductors. That was the first really strong association of physical activity with a reduced incidence of heart attack and of inactivity with an increased incidence of heart attack. But, as the researchers themselves recognized, it was an association, not proof that physical activity - exercise - protects against heart attacks.

Perhaps other factors accounted for the drivers' relative susceptibility to heart attacks. While the conductors were getting their exercise, for example, the drivers were steering the big vehicles through the clogged London streets. Anyone who has ever driven in city traffic knows the kind of aggravation those drivers must have felt. Perhaps the stress of driving played an important role in the statistics. Or perhaps there were subtle genetic differences between drivers and conductors. When the London transit authorities hired conductors they turned down tall men because tall men would have to spend the day uncomfortably stooped within the confined space of a bus. No such height restrictions were applied to drivers.

I mention those caveats merely to point out that a single study, no matter how interesting and suggestive, is insufficient reason for large numbers of men to abandon their easy chairs and start exercising. The evidence linking inactivity with an increased risk of heart attack, however, isn't based on one study alone. The study of London bus drivers and conductors sparked a whole series of similar population studies around the world. With few exceptions, they confirm the main thrust of the London study.

Study followed study. Postal clerks suffered more heart attacks than mailmen who walked their rounds; railroad clerks died of heart attacks at twice the rate of switchmen and maintenance workers. The studies tend to become repetitive. Their collective message is clear, though: Exercise reduces your chances of heart attack.

Perhaps just as important, exercise greatly improves your chances of living through a heart attack. Here are the statistics: Among inactive men suffering their first heart attack, one in five dies; among active men suffering their first heart attack, only one in twenty dies.

To understand how exercise protects against heart attack, let's describe what a heart attack is. Basically, a heart attack is a shortage of oxygen in the heart muscle severe enough to damage muscle tissue. The shortage occurs when atherosclerosis interferes with or stops the supply of blood through the coronary arteries, or when the heart demands more oxygen than the diseased arteries can supply.

Not too many years ago, doctors advised their heart patients to rest, rest, and then rest some more. The advice was logical enough. Activity makes the heart work hard and demand more oxygen. Since a heart patient was known to have diseased arteries, activity carried the risk of excessive demand and thus of another heart attack. These days, however, physicians often urge their heart patients not to rest but to exercise - mildly at first and then more actively. In effect, heart patients are advised to go into training much as an athlete does. Reason: physical training changes the supply-and-demand equation in the patient's favor.

Here's how:

1. Exercise makes the heart a more efficientpump. All muscles need oxygen to produce energy. An efficient muscle needs a lot less oxygen for a given unit of work than an inefficient muscle needs, just as an efficient automobile engine needs less gas per mile than an inefficient engine.

The effect of training on the heart muscle's efficiency is easy to measure. Ask an average, presumably healthy, patient of 40 who's out of shape to walk a mile at a fair pace - let's say in 20 minutes. Then take his or her pulse. You'd probably find the heart pumping at the rate of 110 to 120 beats per minute. Now train the patient by making sure he or she walks that same mile regularly, say three or four times a week, for two months. You'd then find that the pulse rate after the mile had dropped to about 100 beats per minute. The workload has remained the same, but the heart is meeting it with less effort. It has become more efficient.

Several things have happened to permit the heart to work less hard during that walk. The leg muscles have grown more efficient; they extract from the red blood cells a larger proportion of the oxygen in circulation; and there's more oxygen available because exercise also increases the total volume of blood in the arterial system. With the leg muscles using oxygen more efficiently, the heart needn't circulate the blood as fast as it did two months before. It can beat more slowly.

At the same time, the heart itself has become more powerful. With each beat, it squeezes out a larger volume of blood than it did before. That increase in stroke volume, as it's called, also allows the heart to beat more slowly and thus reduces the heart's own demand for oxygen.

2. Exercise increases the number andsize of blood vessels. The circulatory system can be visualized as a marsh fed by a network of arteries and arterioles and drained by veins and venules. Between the arterial system and the venous system lies the marsh, made up of connecting open channels called capillaries. That's where the action is. The cells absorb oxygen through the capillaries in exchange for carbon dioxide, the waste product of the combustion process known as energy.

Physical training forces the whole circulatory system to expand. Some latent capillaries open up, improving the flow of blood in the marsh. Other capillaries grow into arterioles, small arteries. Arteries themselves become wider.

The process has benefits throughout the body (which is a contributory factor in the more efficient use of oxygen), but it is especially significant in the heart, where an interruption in the oxygen supply threatens life. A physically conditioned man is less likely to suffer a heart attack than a decon-ditioned man because his coronary arteries are wider and therefore less apt to clog up with atherosclerotic mush.

If he does suffer a heart attack, he's more likely to survive. Some researchers credit his improved chances to the extra blood vessels that have developed in the heart — the coronary collateral vascularization, as it's known medically. Perhaps the extra blood vessels compensate fully or partly for the blocked blood vessel. Others credit the trained man's survival to his heart's efficiency - to the possibility that the undamaged heart muscle is more likely to work well enough to sustain life than would be the case in an untrained man. Perhaps the complete answer is a combination of the two factors. No matter what the precise mechanism, it's clear that exercise is what brings it into play.

3. Exercise increases the amount of oxygenthe body can actually use. It is possible to determine the oxygen used by having a subject pedal an exercise bicycle while breathing into a large bag. The oxygen the subject has consumed is determined at the end of the test by measuring the contents of the bag. Not long ago, researchers tested nine men between the ages of 32 and 59 who were sedentary not by choice but because they had been blind for at least ten years. Repeated measurements over three months showed that their oxygen uptake was relatively constant and uniformly low, averaging 24 milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of weight per minute (which is the way scientists measure these things). Then the men were trained with daily workouts on the exercise bicycle three times a week for 15 weeks. At the end of that period they were tested again. Their oxygen uptake had increased by an average of 19 per cent.

What does this mean? If you looked at microscopic photographs of the cells of their leg muscles taken before and after exercise, you would notice an increase in the number and size of mitochondria - the part of muscle cells that stores energy. Those cells are now ready to produce much more energy on demand than, they could before physical training. They will therefore require less work of the heart, another factor that allows a trained man's heart to beat more slowly than an untrained man's at a given level of exercise.

4. Exercise may help reduce blood clots that lead to coronary thrombosis and embolism. Blood tends to clot more readily immediately after exercise. That's a natural adaptive process. Human beings in nature didn't exercise for the fun of it. They exercised to hunt their food - or other humans. Their chances of injury were therefore higher than those of today's marathon runner, or even of a professional football player. The faster their blood clotted, the better their chances for survival". At the same time, however, exercise increases the body's production of a substance called fibrinolysin, which dissolves blood clots.

Thus the natural response to exercise is increased clotting ability to stem the loss of blood in case of injury and at the same time increased ability to dissolve a clot once the danger has passed. Some believe that this characteristic response to exercise helps account for some of the protection a conditioned body enjoys against heart attacks. The increased tendency of the blood to clot, it is reasoned, is too temporary for clots to form in coronary arteries. But the increased production of fibrinolysin may well counter the tendency of blood to clot around atherosclerotic deposits.

5. Exercise helps you control yourweight. Exercise, despite some propaganda to the contrary, plays a significant role in weight reduction. You gain weight sure as night follows day when you take in more calories than you spend in activity; you lose weight sure as day follows night when you spend more calories in activity than you take in in your food.

A good deal remains to be learned about the many ways in which exercise benefits the heart. For example, some researchers report that exercise keeps blood cholesterol and triglycerides low. Among population groups with low cholesterol levels, by American standards, are the Bedouins who drive camels across the Sahara desert. Unlike the Japanese, or the Vilcabambans, or the West Malaysian aborigines, the Bedouin camel drivers eat saturated fat in quantities that would be disastrous for Americans. On their treks, camel butter becomes the center of the diet. Why doesn't the high-fat diet result in high blood-cholesterol levels? It's widely believed that the Bedouins just walk it off.

Exercise may also play a role in controlling high blood pressure, according to several reports. Much" more research will be needed to confirm that interesting possibility. Still, the known physiological effects of exercise on the heart are. sufficiently beneficial to make a planned program of exercise an obvious part of any preventive health regimen.

The benefits of exercise don't end with the observable physical effects. The subjective, psychological effect of exercise should not be overlooked. Many people who have begun to exercise and who have stayed with it until exercise has become a habit report an increased sense of well-being and a greater tolerance for the psychic assaults of everyday life. They are less nervous, they sleep better, they are less open to the damaging physical effect of stress.

Many people who exercise soon learn how much fun they can have while protecting the heart. They may take up tennis, or ride a bicycle long distances, or get back to one of the team sports like basketball or touch football that provided pleasure in their younger days. Once that happens, the physical effects of smoking hit home. One can intellectually accept the idea of severely damaged lungs from smoking, but it's not until you run out of breath halfway through your first set of tennis that you're likely to really do something about the habit. Lots of patients who have tried in vain to give up cigarettes finally report success when motivated by the desire to play winning tennis or to get involved in pick-up basketball games on the weekend - or just to take a brisk walk on a fall day without wheezing and coughing.

Convinced? Ready to rush out and run a mile? Don't.

Exercise can also kill you if you go at it the wrong way. And not all exercise is equally beneficial.

THE athletes who competed in the 1970 Olympic marathon covered more than 26 miles at a fast trot. The winner finished in two hours and fifteen minutes. To the hundreds of thousands of Americans who watched the Olympics from an easy chair in front of a television set, the endurance of marathon runners appears incredible.

There is no television in the mountains of northern Mexico, so we don't know how modern marathon runners might impress the Tarahumara Indians who live there. Probably not much. The Tarahumara begin to run as soon as they learn to walk. Running is their principal means of livelihood. They often hire themselves out as human moving vans because they can run'farther and faster than their main competition - donkeys. The Tarahumara hunt some animals by chasing them for days until the quarry drops from exhaustion. Running is also their main sport. Not long ago a medical observer clocked eight Tarahumara men between the ages of 18 and 48 during a 28-mile kickball race over craggy terrain. Including time spent looking for balls kicked off course, the winning team finished the race in four hours and forty-five minutes - an average speed of 5.8 miles per hour.

Deaths from cardiac disease or circulatory problems are unknown among the Tarahumara.

I mention the Tarahumara only as an example of the kind of physical activity the human body is capable of - the kind of activity, indeed, for which nature designed it. No serious physician expects modern, sedentary Americans to revert to an aboriginal life style. Civilized life, after all, does include a few pleasures other than running, even a few goals other than the avoidance of heart disease. Nor is it necessary for Americans to run for hours each day. Careful laboratory studies of the physiology of exercise have shown that you can gain substantial protection against a heart attack with only one half-hour workout every other day. But the workout must consist of the right kind of physical training.

There are three possible results of physical training: an increase in the size and strength of the skeletal muscles; increased agility or the development of specific skills; and increased physical endurance. The same exercise can bring more than one desirable result; basketball, for example, increases both agility and endurance.

As far as the heart is concerned, however, endurance is the only result that counts. Unfortunately, many extremely active people, including many people in planned exercise programs, fool themselves into the mistaken belief that they are doing their hearts some good when they are merely building other muscles or becoming proficient at a sport.

Endurance and endurance training are words with a tough ring to them. Yet it's surprisingly easy to build a safe and effective endurance training program into your daily schedule. Here's how to start: Put down this article, get up out of your chair, go outside, and take a walk. Walk briskly, as if marching in a parade, for 15 minutes.

Is it cold out? Dress warmly.

Too hot? Hold off until the cool of evening, or take your walk first thing in the morning, before breakfast.

Raining? Wear rubbers and carry an umbrella.

If you don't like walking in the rain, drive to a shopping mall, park your car, and take your walk there.

However, if there's some reason why it's better not to leave the house at all - a hurricane is raging outside, or you fear there are muggers prowling the neighborhood - just march around your home for 15 minutes. Go from room to room. If there are stairs, climb them. Beware of stray toys; ignore jeering children; and tell your spouse you will explain everything later.

This excerpt is from Dr. Levitas'book, You Can Beat the Odds on a Heart Attack, to be published thismonth by Bobbs-Merrill. Theauthor, a member of the Class of1929, is chief of the cardiac stresstesting laboratory at Hackensack(N.J.) Hospital.

® 1975 by Irving H. Levitas, M.D.

"If a hurricane is raging outside or you fearmuggers are prowling the neighborhood, justmarch around your home for 15 minutes."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBlack in the White Academy

May 1975 By WARNER R.TRAYNHAM -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleWhere the Grass Looks Green

May 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

May 1975 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., HARTHON I. MUNSON -

Article

ArticleThe Long Walk

May 1975 By OLIVE TARDIFF

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe President

June 1980 -

Feature

Feature"Fraternities Are in Trouble"

MARCH 1972 By DAVID WRIGHT '72 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOught Ought

NOVEMBER 1996 By Joe Mehling '69 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1957

July 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

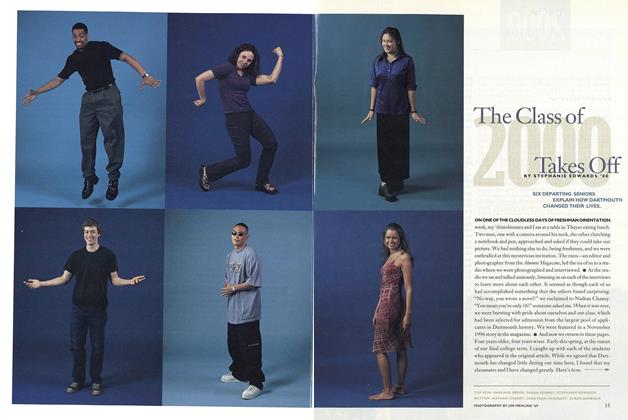

FeatureThe Class of 2000 Takes Off

JUNE 2000 By STEPHANIE EDWARDS ’00 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/August 2005 By Thomas Vieth '80