REMEMBER, back in 1971, how you laughed and lorded it over your friends from Cambridge after Ted Perry kicked the 46-yard field goal as the clock ran to zero and Dartmouth escaped from Harvard Stadium with a 16-13 win?

And how about all those other autumn afternoons over the years when Dartmouth, demonstrating the timing otherwise reserved only for cavalry regiments that stormed across the silver screen to save the homesteaders, won more than its share of the cliffhangers. Remember?

Felt pretty good, didn't it? Well, if you were around Yale Bowl on the first day of November you discovered first-hand how the guys who have been on the short end so often felt while you whooped it up. That was the afternoon when the shoe was on a Blue foot in another chapter of the perilous life called Ivy League football. The culprit was a Yale junior named Randy Carter, a specialist whose longest field goal to that moment had been a 38-yarder. Carter's 47-yard attempt rode the winds and negated the Dartmouth cavalry's charge that had produced a 14-13 lead less-than a minute before and, as the clock again came to zero, Yale had a 16-14 victory. (It cuts both ways, as the Elis learned in their last-minute, last-game loss to Harvard for the championship.)

Two plays and two seconds. That's the difference between being on the brink of an Ivy League title rather than beating Princeton merely for fourth place on the final day of the season. If you think you feel bad, consider Jake Crouthamel, the coach who accepts defeat (and ties fall into the same category) about as graciously as Attila the Hun. A coach and his players are wont to remember the losses much longer than the wins. A negative report only sounds good when it comes from the doctor.

Two plays and two seconds. Make it three plays if you consider the entire season. That's how close it's come to being like the good old days when Dartmouth collected ten Ivy League championships. days that seem long ago but really aren't when you stop and think. It's just that you get too accustomed to the good life.

The plays: 1) the Massachusetts recovery of its own fumble in the end zone that provided the points in Dartmouth's 7-3 loss to a team that proceeded to win eight straight; 2) a 65-yard play, five of it gained on a third-and-eleven pass from Brown's quarterback, Bob Bateman, to flanker Charlie Watkins, and the rest collected by Watkins on a sideline dash that created the 10-10 tie with the Bruins; 3) the Carter field goal as the clock ran out at Yale. Instead of being a Dartmouth win (and Yale's second loss in the League), it was Dartmouth's second loss. Combined with the tie, it put Dartmouth into also-ran status.

The other loss came the week before at Harvard, the only team that was a convincing winner over Dartmouth on the scoreboard, 24-10. In a game played in driving rain, Dartmouth contributed four interceptions and four lost fumbles to its downfall. The Green had only three other passes intercepted and three other fumbles lost in the other seven games prior to the finale.

Not so incidentally, this was the season that saw Dartmouth earn its 500th all-time football victory, a 22-17 decision at Columbia (also Dartmouth's 300th and 400th victim in 1937 and 1960). At Baker field sophomore halfback Sam Coffey emerged as one of the bright new running backs on the Hanover scene, and the game, not nearly so close as the score would indicate as Dartmouth moved from a 10-3 halftime deficit to a 22-10 advantage before the Lions scored against the reserves, helped ease the agony of the successive tie-loss-loss experience with Brown, Harvard, and Yale.

The Yale game, incidentally, produced one of the most exciting minutes of football in Ivy history. Down 10-0 at halftime, Dartmouth dominated the second half and took the lead with 44 seconds left to play when Kevin Case, the quarterback who took over after Mike Brait's nose was broken early in the final period, ran a keeper on third down at Yale's seven. He fumbled the ball inside the five, it skittered into the end zone, and split end Harry Wilson covered it for Dartmouth.

The only problem thereafter was that unlike some earlier games when Dartmouth had its chances but ran out of time, the clock didn't run out fast enough in the Bowl.

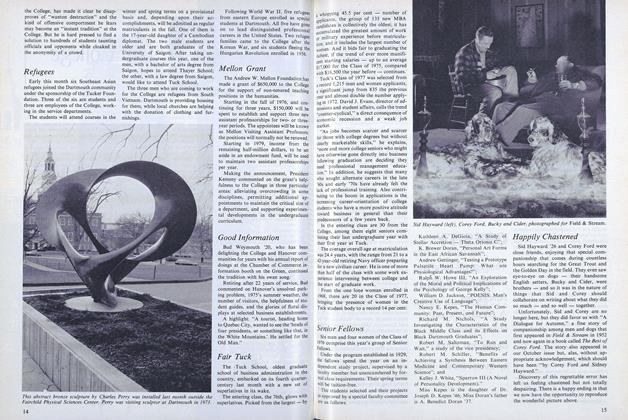

The 33-10 win over Cornell, the ninth straight time that Dartmouth has defeated the Red, was the optimum afternoon for Brait and Tom Fleming, the fleet split end who suffered an ankle injury during the Penn game in early October, missed the Brown and Harvard dates and was willing but still not ready for Yale. "Tom's mere presence on the field gives our entire team a lift," said Crouthamel. "He has the speed to break a game apart with a single play and the defense has to think about him on every play."

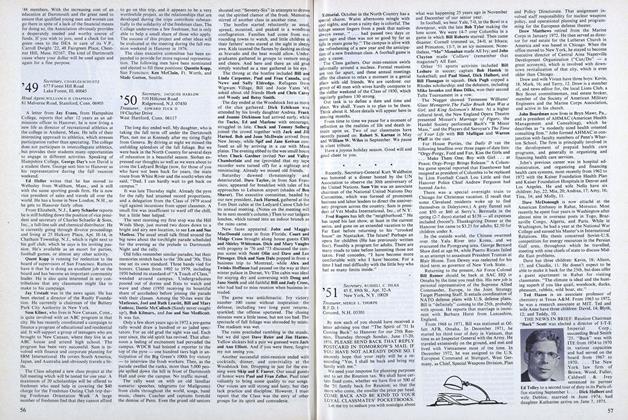

Against Cornell, Brait completed 13 of 19 passes for 244 yards and three touchdowns. The touchdowns all went to Fleming, who caught seven passes in all for 159 yards - a Dartmouth game yardage record for receptions. The TD catches tied a Green record that Myles Lane set and equaled twice in 1925 and 1927 and that was also equaled by Tom Rowe against Yale in 1948.

Princeton wouldn't - or couldn't - pay much heed to this Brait-to-Fleming performance. At Palmer Stadium, on the last Saturday of the campaign, the two Dartmouth seniors combined for scoring passes of 70 and 85 yards on the way to a 21-16 win.

So the season ended with the Green in fourth place with a 4-2-1 record. One can only wonder what might have happened if Fleming had been healthy for play against the three teams that finished ahead of Dartmouth in the final standings.

Tom Fleming backpedals into the end zone for one of his three scores against Cornell.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureQuite Contrary

December 1975 By SAMUEL PICKERING -

Feature

FeatureThe Assault On Quebec

December 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

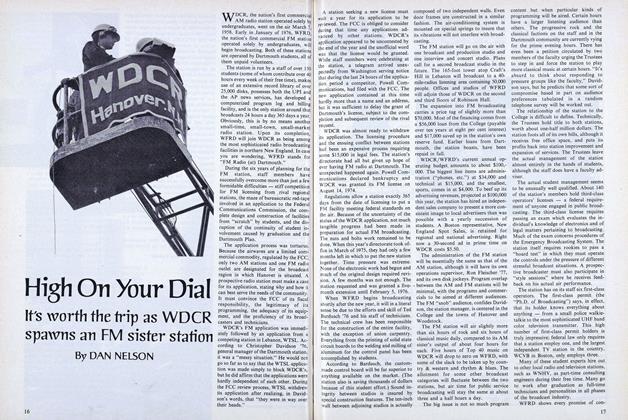

FeatureHigh On Your Dial

December 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Radical Union

December 1975 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

December 1975 By DOUGLAS WISE, BARRY R. BLAKE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

December 1975 By JACQUES HARLOW, EDWARD TUCK II