Now, kids are different. You can show them a photo of Charlie Starrett, sixshooters in hand, and they won't blink. Show them a picture of some android robot, and they'll swoon. It is the rare nostalgic adult who'll ring the former cowboy actor up at 4:00 a.m. in his Laguna Beach, California home:

"Hello? Is this Charlie Starrett?" "Yes, it is."

"Why, I thought you were dead!" Charlie Starrett doesn't mind that kids today take their dosage of good guys and bad guys in space. But the early morning phone calls do bother him. "That's a hell of a way to be woken up 'I thought you were dead!' " Especially because after 180 moviies and a thousand barroom brawls, the Durango Kid is more spirited than his couple dozen white horses ever were.

There are those of us in the younger generation who prefer a Starrett to an R2-D2, flesh and blood over gears and diodes. Never mind that Hollywood studios often turned their cowboy stars into some kind of robot. I still prefer sunsets and sagabrush to intergalactica. What a thrill then, to meet Charlie Starrett when he came east with wife Mary to receive a distinguished alumnus award from Worcester Academy. ("They must be scraping the bottom of the barrel.") We met at Lou's. Starrett's energy fairly lit up the place, something a robot could do'only if it blew a fuse.

He belongs to that group of actors who left Dartmouth in the twenties, did vaudeville, Chautauqua, and theatre, and, not being California natives, discovered Hollywood as Hollywood discovered them. Louis Jean "Bus" Heydt '26 and Bob Williams '26-well known character actors in their own right were Starrett's Psi U brothers and backlot pals. But it was Starrett who achieved greatest stardom when he replaced Buck Jones as Columbia Picture's leading cowboy. For seven years, Starrett was the Durango Kid the Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and Hopalong Cassidy of Columbia. He was one of the top money-making western stars, according to Motion Picture Heralds fame poll. "A rough-riding, sharp-shooting hunk of a man," drooled Movie Thrills magazine in 1950.

Starrett spent almost five years in theater before he went to Hollywood. He played the Chautauqua circuit after graduation, touring with Cincinnati's Stewart Walker Stock Company in such memorable hits as The Goose Hangs High. Lest success swell his head, a classmate providedthe June 1927 ALUMNI MAGAZINE with this review of Starrett's debut at New York's Heckshaw Theatre: "He had a good scene where he jumped out from behind a cabinet and said, 'Hands up!' My, it must be wonderful to be an actor."

With the talkies came "the second gold rush," Starrett recalls, and the young actor went west in 1931. The studios hyped Starrett's 25-yard runback for a touchdown in a cliffhanger against Cornell when he played fullback for Dartmouth. They cast him in such films as The Quarterback,The Sweetheart of Sigma Chi, and Murder onthe Campus. He later told the Valley News that he made more yardage for Paramount than he ever did for Dartmouth. Starrett could also ride a trot inside the Psi U house once cost him $100 in floor repairs -so West of Tombstone, Lawless Plainsman, and many other horse operas were added to his credits. When Columbia took Starrett away from Paramount-"I like to say I did my graduate work at Columbia." the publicity department announced that with Charlie Starrett went "a solid following of fans who like their entertainment rugged and active."

He averaged eight films a year as the Durango Kid, riding with such comic sidekicks as Ukelele Ike. The studio manipulated his "rugged and active" image from a standard shot-glass and six-gun cowpoke who rode off with the heroine to a tumbleweed Robin Hood who wouldn't touch liquor or women. No ordinary cowboy, the Durango Kid would walk into a bar, slap down his two bits, and say, "Buy yourself a drink. Which way to Laredo?" Then he would ride off into the sunset, alone.

Starrett is still close physically to the six-foot-two-inch, 180-pound cowboy, though civilian clothes replace form-fit jeans, tailored shirts, a bright bandana, twirling spurs, and the white hat. His smile still blends sincerity with mischief as it does in the old studio stills. It was, in fact, something of a problem for the studios that Starrett's off-screen exploits were every bit as sincere as his on-screen ones. Starrett is number ten of the original 17 founders of the Screen Actor's Guild. "The heads of the studios had complete creative control over creative talent. They pretty much controlled how much we could earn and how fast we could advance," he recalls. In 1933, the founding actors met secretly in Boris Karloff s garage and drew up the Guild charter. Starrett has a gold card now, a lifetime membership as one of the "instigators" of an organization which now boasts 40,000 members.

Starrett retired from pictures in 1952. He and Mary, soon to celebrate their 55th anniversary, moved first to the High Sierras, later to Laguna Beach. In the meantime, they have "collected islands," from Bora Bora to Mykonos: "I just like to see what the fellow on the other side of the hill is up to." The Starretts have rarely missed a Harvard-Dartmouth game or a chance to visit the College. He and Mary were married at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Hanover in 1927. "It's really homeplate to me. I'd like to matriculate again."

After Starrett veered from the subject the third or fourth time, I got the feeling that his days in Hollywood were no more important than his days in Athol, Mass., where he was born in 1903, or in Hanover, or in Laguna Beach. He'll say he was no expert on horseback and that he was slow on the draw. And he doesn't go to many movies today. "I have no taste for a camera, either on or off." When television came along, Starrett said, "the old closeness of Hollywood broke down." There are still good and bad movies being made "just like always" but he thinks too much money is spent making both. In the forties, feature movies rarely cost more than a million to produce; today, the average studio movie costs at least ten times that.

If Charlie Starrett does get talking about the Durango Kid, he's liable to stop, pause a moment, then chuckle, "I rode for the West that wasn't." It's a kind of a verbal pinch, and it's helped Charlie Starrett survive the hype and glamour of Hollywood. He's lasted, not as the Durango Kid, but as Charlie Starrett. The secret may be family, friends, and a steady focus on the present. Those 4:00 a.m. phone calls might just be from this year's superstar, eager for advice from a survivor.

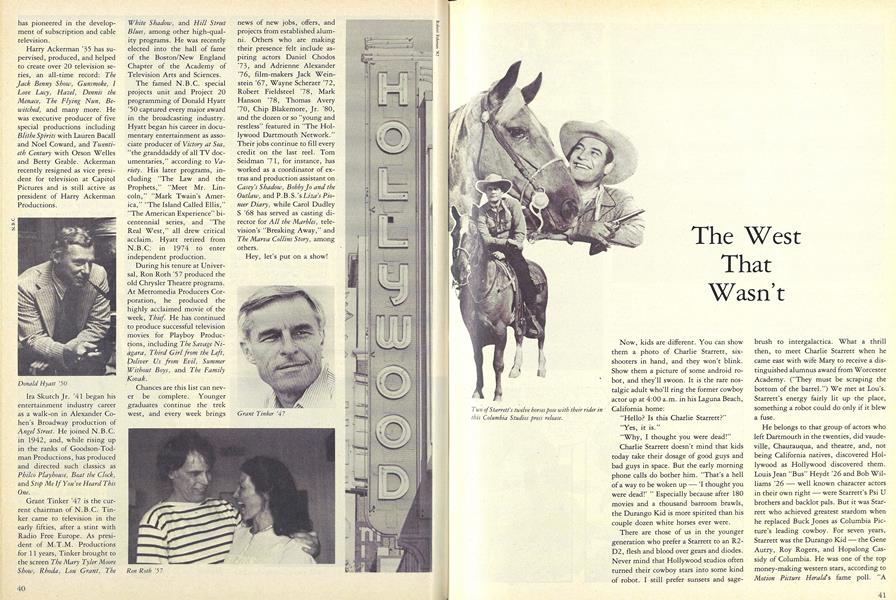

Two of Starrett's twelve horses pose with their rider inthis Columbia Studios press release.

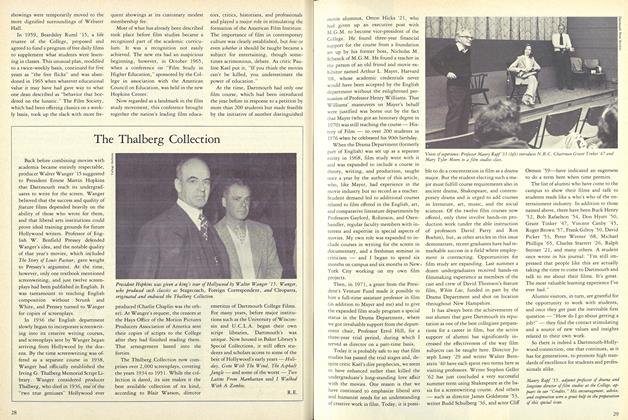

In Mr. Skitch (above), a pre-Durango Starrett(1933) plays a young cadet who falls in love withthe daughter of a less-than-thrilled father, played byWill Rogers. Starrett was a Dartmouth fullback(right), though not quite the football hero in school ashe later was on film. These Durango Kid comicsportray nothing less than "The Movies' Most Colorful Western Star."

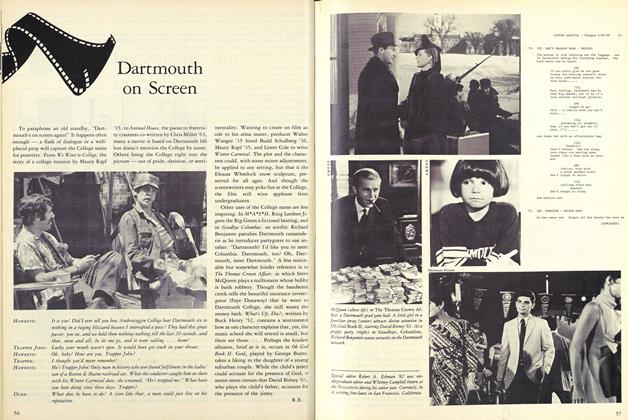

Charlie and Mary Starrett today: "I'd like to matriculate again."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

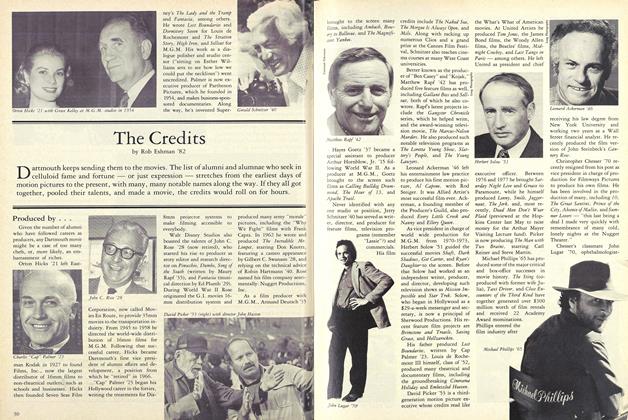

FeatureThe Credits

November 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

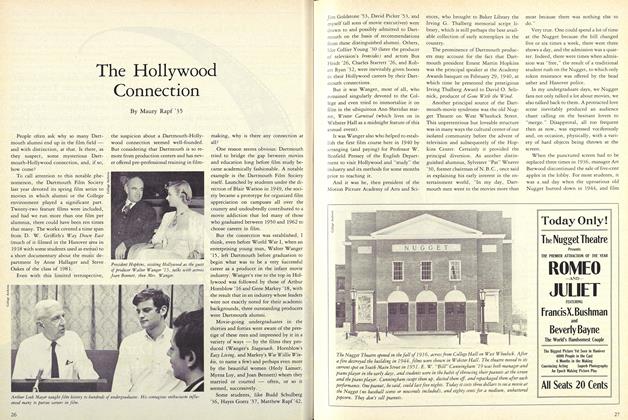

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

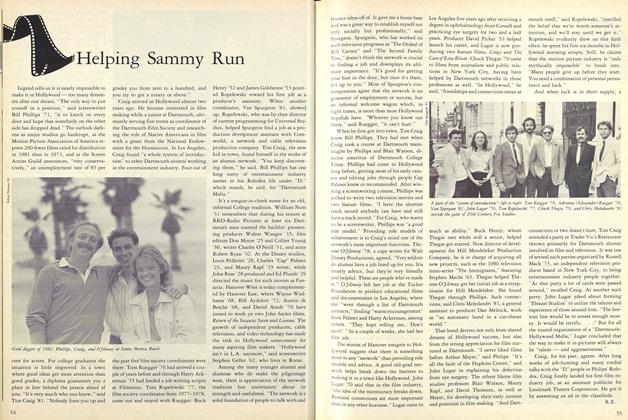

FeatureHelping Sammy Run

November 1982 -

Feature

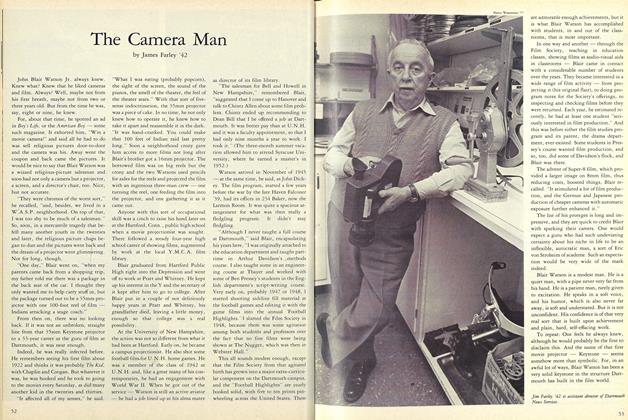

FeatureThe Camera Man

November 1982 By James Farley '42 -

Feature

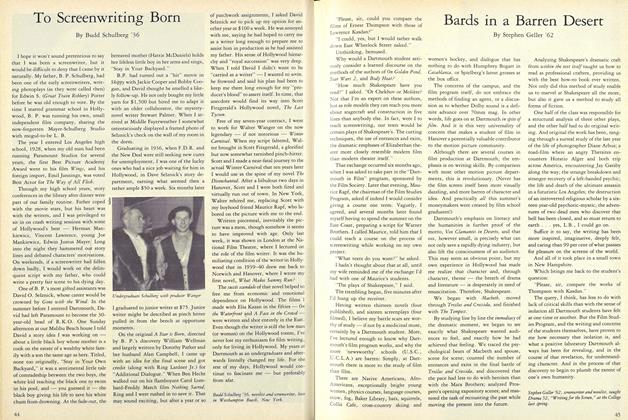

FeatureBards in a Barren Desert

November 1982 By Stephen Geller '62

R.E.

Features

-

Feature

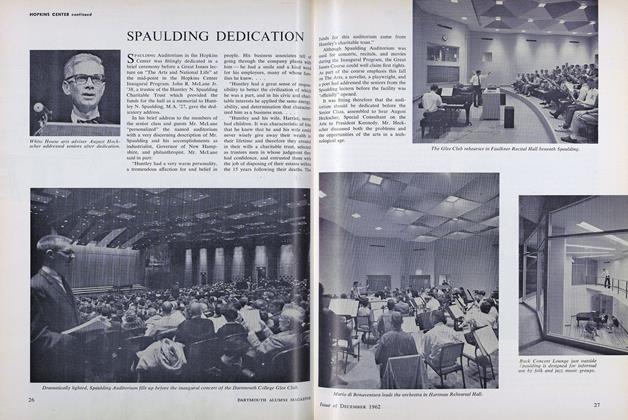

FeatureSPAULDING DEDICATION

DECEMBER 1962 -

Feature

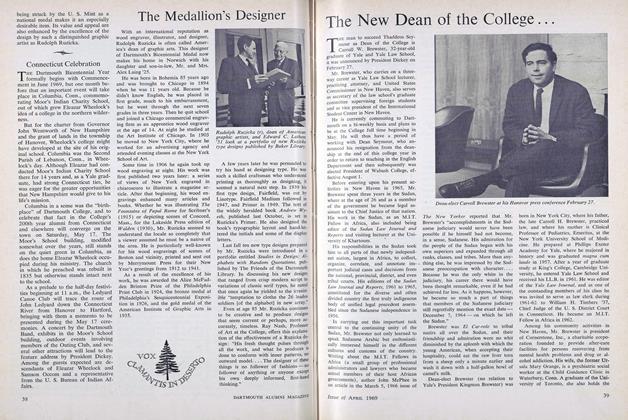

FeatureThe New Dean of the College...

APRIL 1969 -

Feature

FeatureMatthew Wysocki Professor of Art 300 St. Nicks in D single collection

January 1975 -

Feature

FeatureChallenge

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Colleen Sullivan Bartlett '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Dissenting Opinion

Nov/Dec 2010 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Cover Story

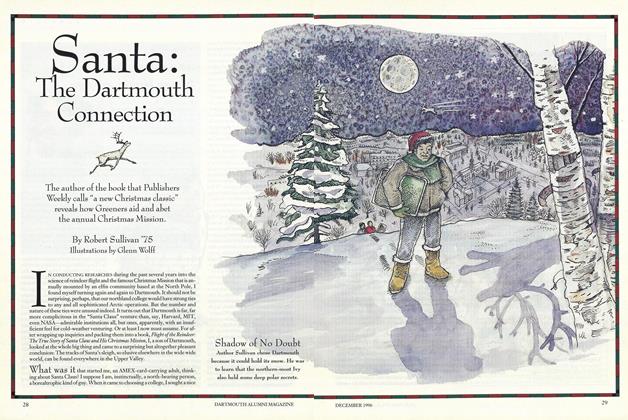

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

DECEMBER 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75