For the "back-to-the-woods" syndrome recently in vogue, particularly amont the young, listening to ALAN V. TISHMAN'39, a sort of ultimate urbanite committed to the American city by faith, fortune, and affection, offers a persuasive antidote.

Executive vice president of Tishman Realty and Construction, vice chairman of the Committee for a Better New York, working advocate of efforts to strengthen the amenities of urban life and combat its blights, Tishman is unwavering in his conviction that "the future still lies in our cities."

He finds city living stimulating and convenient, its hazards grossly exaggerated. Although they maintain a home in Connecticut, the Tishmans spend much of their time in their New York apartment, whence they sally forth unconcerned for evening walks, a perilous lark according to rural types. As for Hollywood's current image of high-rise apocalypse, Tishman calls The Towering Inferno "absolutely ridiculous."

Although the company, founded in 1898 by Alan's grandfather, went public in 1929, the family still owns controlling interest and constitutes the top level of management. His father is chairman of the board, his elder brother the president; a cousin is executive vice president for construction, as Alan is for real estate. Except for four years in the Navy, from which he emerged in 1945 as a lieutenant commander, having been commended - by the Army, no less - he has been with the company since graduation.

It was only after the war that Tishman expanded beyond its New York market, first into Los Angeles. Initial western skepticism waned swiftly, and by the late '6os the firm had become L.A.'s biggest office landlord. "Tishman made Wiltshire Boulevard what it is today," commented a local realtor. "They are the only ones with the brains to come in and tell us to build up and not out." They carried the export of innovation into Chicago in the '6os, violating the shibboleth that business had to be carried on in the Loop, breaking out across the Chicago River to build a three-tower complex over air rights purchased from the Illinois Central Railroad.

Company assets rose from $95 million in 1964 to more than $422 million in late 1973, when Tishman owned over 10.5 million square feet of rentable space in 23 buildings — including Phila- delphia's Centre Square, designed by John-Robertson Cox's current firm (see facing page) — with four more under construction. It had also built or was building such notable client-owned structures as the Alcoa Theme Center in Los Angeles; the Renaissance Center on the Detroit River; Chicago's John Hancock Building (not the almost comically misbegotten Boston edifice of the same name), first to top the Empire State; and the World Trade Center, which returned the altitude title to New York.

Business Week calls Tishman "a one-industry conglomerate," offering clients the same package of services evolved for their own buildings: assembling the site (very quietly); choosing an architect for whom their own design staff serves as critic; arranging financing; acting as general contractor; going on often to handle leasing and management. A research subsidiary helps manufacturers develop new products and techniques. Tishman's involvement in urban renewal and slum rehabilitation projects provides clients with working laboratories to test materials and methods for low-cost renovation of delapidated housing.

Soaring energy prices and the high cost of money have had a severe impact on the industry as a whole, Tishman readily concedes, pointing out that his firm's fuel and electric bills now average for two months what they did for a year before the Arab oil boycott. "If our leases didn't provide for handing increased costs along to tenants, we'd be out of business." He concurs in "the obvious need to conserve energy" and to curb engineering practices which have led to profligate use of power.

The Committee for a Better New York and the various humanitarian enterprises Tishman supports with his time and talents typify his positive approach to the problems that plague the city. The committee, originally formed to stem the tide of corporate moves to the suburbs, works closely with municipal government to upgrade services and stress the positive aspects of urban living. Companies and families that have fled to the suburbs are having second thoughts, he maintains, as they discover that what they sought to escape has followed them instead: crime rates, leveling off in New York, have risen sharply in outlying areas; expenses have proven higher than anticipated, while city rents are down, largely in response to vacancies caused by the exodus; suburban services are inadequate to cope with the influx, and such urban amenities as easy accessibility, mass transportation, and cultural activities are sorely missed by the refugees.

Tishman's alternative to illusory escape is forceful action to alleviate the city's social ills and preserve its advantages. For the past two years, he has been chairman of the maintenance campaign for the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies. Fie is an officer or trustee of the Mount Sinai Medical Center and Hospital; Odyssey House, a drug rehabilitation agency; the Jewish Child Care Association; the American Museum of Natural History.

A loyal alumnus, he serves the College well through class responsibilities and fund-raising committees, and he enjoys coming back to Hanover on occasion. But the mist that clouds many a Dartmouth man's eye when he dreams of returning to settle down near the College is notably absent from Alan Tishman's.

The country may be a great place to visit, but he wouldn't want to live here.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureStar Birth, Star Death, and Black Holes

February 1975 By DELO E. MOOK -

Feature

FeatureHONOR: The Vanishing Principle

February 1975 By JAMES A.W.HEFFERNAN -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Rip-off

February 1975 -

Feature

FeatureSome People Are Good Skiers

February 1975 By V.F.Z. -

Article

ArticleThe Gospel According to Marcus

February 1975 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

February 1975 By J.H.

Article

-

Article

Article"The Reins Change

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleIn Brief ...

December 1961 -

Article

ArticleEnergetic Conservation

Jan/Feb 1981 -

Article

ArticleCrossing the Green

NOVEMBER 1984 -

Article

Article"A BISHOP AMONG HIS FLOCK"

May, 1914 By Ethelbert Talbot '70, L. S. H. '70. -

Article

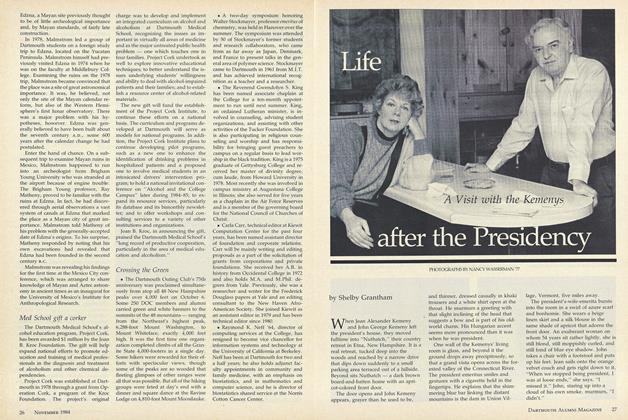

ArticleKEMENY'S CRYSTAL BALL

May/June 2004 By Lee Michaelides