A traveling exhibition that originated at Dartmouth's Hood Museum unleashes the first of all passions.

AST FALL JOY KENSETH,

professor of art history, swept Dartmouth's Hood Museum of Art back to sixteenth- and seventeenth- century Europe, back to the era she calls the Age of the Marvelous. It was a time when lingering medieval and religious concepts of miracles and mysteries coexisted with the Renaissance's new-found admiration for classical knowledge and fascination with the discoveries, both geographic and scientific, that were expanding human experience. "The Age of the Marvelous" exhibition, which Kenseth conceived and curated, recreates that time when the world seemed new and so much in it wondrous and astonishing.

Despite centuries of marveling at the power of wonder—Rene Descartes, for example, expounded back in 1649 that wonder is the first of all passions—"The Age of the Marvelous" is the first comprehensive museum exploration of the Renaissance fixation on natural and man-made wonders and marvels, an obsession that, curiously enough, birthed the very notion of museums. A record number of Hood visitors saw the exhibition before it traveled to the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. You can still catch "The Age of the Marvelous" at Houston's Museum of Fine Arts from May 24 to August 23 and at Atlanta's High Museum of Art from October 6, 1992, to January 3, 1993.

The following is a printed tour in Kenseth's own words of what critics have called the most original exhibition ever to grace the Hood.

STOP AT THIS PLACE (CURIOUS ONE), FOR here you behold a*%g|ld :iri a home, indeed in a Museum. it is a microcosm of all rare things..." So invited the inscription over the entrance to the Kunst- und Wunderkammer, the art and wonder room, assembled by Dr. Pierre Borel in seventeenth- century France. He, like other wealthy and educated Europeans of the time monarchs, aristocrats, natural scientists, doctors, lawyers, educators amassed private collections of the marvels that flowed into Europe from all parts of the globe. Cabinet-lined wonder rooms housed diverse collections ranging from holy relics and antiquities to rare botanical and zoological specimens, artifacts from foreign cultures, scientific and mechanical instruments, and finely crafted works of art. Alligators hung from ceilings, and curio cupboards displayed hundreds and sometimes thousands of objects, the arrangements so artful as to be considered marvels in themselves.

MORE THAN ANYTHING, IT WAS the discovery of the New World that patapultedi the marvelous into vogue as Europe was inundated with exotic wonders more exciting than fiction. There was the Brazilian toucan with its great beak and New Guinea's fabulously plumed birds of paradise, long thought to be footless. The size, oddness, or complex shapes of New World flora corn, pineapples, bananas, potatoes amazed people. Of all the wonders in the New World, however, the inhabitants aroused the greatest curiosity, and their appearance, rituals, ingenuity in hunting, methods of making beer, and strange habit of "drinking smoke" out of tobacco-filled pipes were documented in words and pictures.

Advances in science and technology opened still other astounding vistas: telescopes scanned the heavens while the microscope, itself considered a marvel, brought to light such unlikely wonders as the flea and the eyes of the common fly. Technology also advanced the marvelous in art. Theatrical designers contrived laborate illusions on stage and hydraulic engineers produced spectacular garden fountains. Refinements in the lathe allowed artisans to execute tiny and intricate items of wood, ivory, and other prized materials as they tried to rival the ingenuity of God's creations.

Ironically, as wonder rooms proliferated across Europe, the marvelous became the commonplace. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century scientific rationality had displaced wonder, and critics were urging artists not to dazzle their audiences but to educate them instead. The Age of the Marvelous had given way to the Age of Reason.

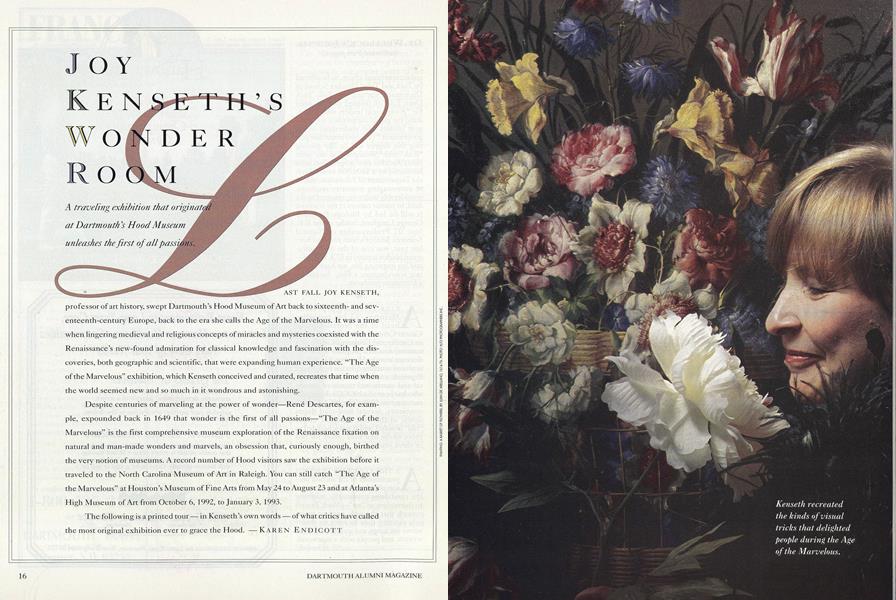

Kenseth recreatedthe kinds of visualtricks that delightedpeople during the Ageof the Marvelous.

The Hood used Ferr ante Imperato's1599 woodcut of a Renaissance wonderroom as a blueprint for the exhibition.

Wonder-room oddities in the exhibitioninclude ivory-inlaid guns of kings, anautilus shell transformed with gold intoa giant snail, and a bird of paradise.

The era wasalso an age ofexploration,on both thegrand scaleillustratedin JoannisBlaeu's 1662 Geographia Maior (below), andon the smallscale madepossibleby RobertHooke'smicroscope, (right).

Europeansmarveled atBrazilians"drinkingsmoke" in thenew Eden.

With tronnpe-l'oeil paintings,seventeenth-century artists workeda kind of magic on the beholder.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

April 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

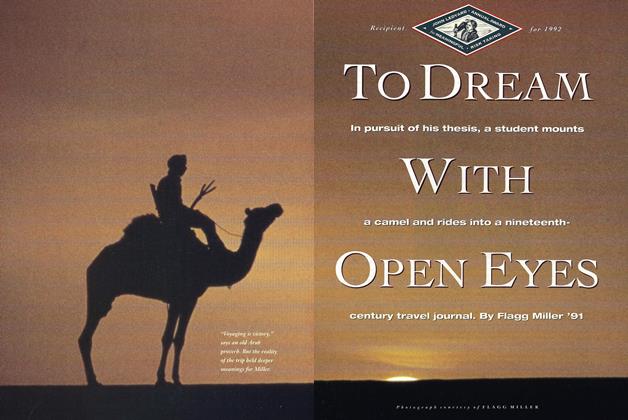

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

April 1992 By flagg Miller '91 -

Feature

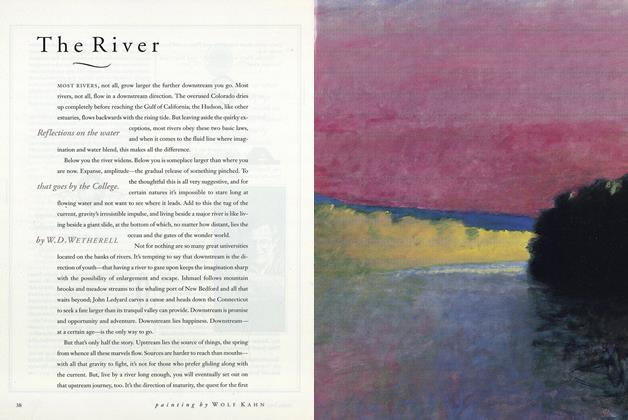

FeatureThe River

April 1992 By W. D. Wetherell -

Feature

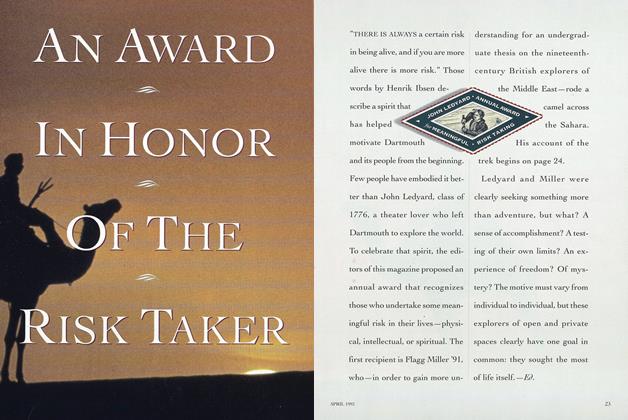

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

April 1992 -

Article

ArticleThe Imagination Unbound

April 1992 By Ulrike Rainer -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1992 By "E. Wheelock"

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleProfessor of Economics William L. Baldwin

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWhy the Novel Matters

May 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleGrade Deflators

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Cautionary Tale

April 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSpace Politics

March 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Interview

InterviewDartmouth on the Brain: Green Research and Gray Matter

SEPTEMBER 1999 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureStudents

June 1980 -

Cover Story

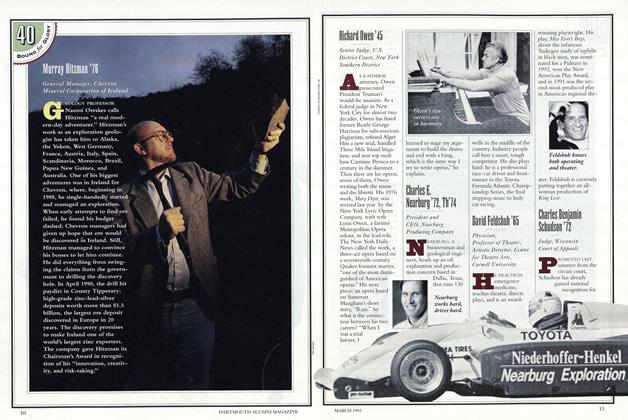

Cover StoryCharles E. Nearbury '72, Th'74

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureThe Magazine Has A Birthday

OCTOBER 1958 By C.E.W. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLooking for Mr. Goodjob

MAY • 1987 By Jock McDonald '87 -

Feature

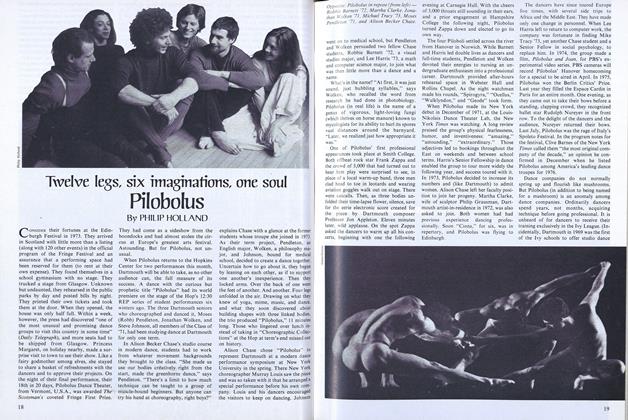

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Feature

FeatureThe Mold

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Warren Cook '67